Author: Onyekachi Nwafor (CEO, KatexPower).

Topic: Electrification of remote villages.

Tool type: Teaching.

Relevant disciplines: Energy; Electrical; Mechanical; Environmental.

Keywords: Sustainability; Social responsibility; Equality, Rural development; Environmental conservation; AHEP; Renewable energy; Electrification; Higher education; Interdisciplinary; Pedagogy.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

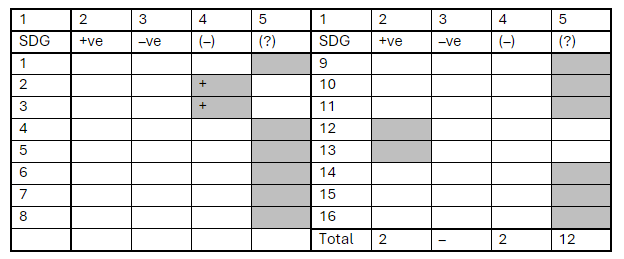

Related SDGs: SDG7 (Affordable and Clean Energy); SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities); SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Educational level: Intermediate.

Learning and teaching notes:

This case study offers learners an explorative journey through the multifaceted aspects of deploying off-grid renewable solutions, considering practical, ethical, and societal implications. It dwells on themes such as Engineering and Sustainable Development (emphasizing the role of engineering in driving sustainable initiatives) and Engineering Practice (exploring the application of engineering principles in real-world contexts).

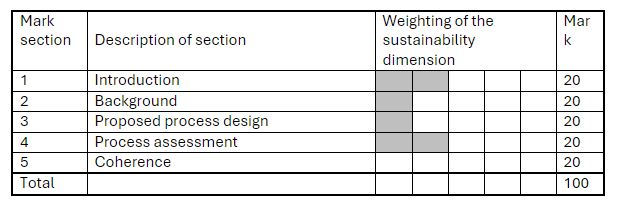

The dilemma in this case is presented in six parts. If desired, a teacher can use Part one in isolation, but Parts two and three develop and complicate the concepts presented in Part one to provide for additional learning. The case study allows teachers the option to stop at multiple points for questions and/or activities, as desired.

Learners have the opportunity to:

- Recognise the significance of the SDGs in engineering solutions;

- Enhance their skills in applying sustainable engineering practices in real-world scenarios.

- Delve into the complexities of implementing off-grid solutions.

- Navigate through the ethical considerations of deploying technologies in remote, often vulnerable, communities.

- Engage in critical thinking to balance technological, societal, and environmental aspects.

Teachers have the opportunity to:

- Highlight the importance of SDGs in engineering.

- Facilitate discussions on ethical implications in technology deployment.

- Evaluate learners’ ability to devise sustainable and ethical engineering solutions.

Learning and teaching resources:

- SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy – Understand the global emphasis on clean energy and its implications

- African Development Bank: Off-Grid Revolution

- The World Bank: Mini Grids in Africa

- International Energy Agency: Energy Access Outlook: from Poverty to Prosperity

- James P Dunlop; Photovoltaic systems; ISBN: 978-0826913081; American Technical Publishers. Photovoltaic Systems is a comprehensive guide to the design and installation of several types of residential and commercial PV systems.

- DGS; Planning and installing photovoltaic systems: A guide for installers, architects and engineers; ISBN: 978-1849713436; Planning and installing series.

In accordance with a report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and statistics provided by the World Bank, approximately 633 million individuals in Africa currently lack access to electricity. This stark reality has significant implications for the remote villages across the continent, where challenges related to energy access persistently impact various aspects of daily life and stall social and economic development. In response to this critical issue, the deployment of off-grid renewable solutions emerges as a promising and sustainable alternative. Such solutions have the potential to not only address the pressing energy gap but also to catalyse development in isolated regions.

Situated in one of Egypt’s most breathtaking desert landscapes, Siwa holds a position of immense natural heritage importance within Egypt and on a global scale. The region is home to highly endangered species, some of which have restricted distributions found only in Siwa Oasis. Classified as a remote area, a particular community in Siwa Oasis currently relies predominantly on diesel generators for its power needs, as it remains disconnected from the national grid. Moreover, extending the national grid to this location is deemed economically and environmentally impractical, given the long distances and rugged terrain.

Despite these challenges, Siwa Oasis possesses abundant renewable resources that can serve as the foundation for implementing a reliable, economical, and sustainable energy source. Recognising the environmental significance of the area, the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) declared Siwa Oasis as a protected area in 2002.

Part one: Household energy for Siwa Oasis

Imagine being an electrical engineer tasked with developing an off-grid, sustainable power solution for Siwa Oasis village. Your goal is to develop a solution that not only addresses the power needs but also is sustainable, ethical, and has a positive impact on the community. The following data may help in developing your solution.

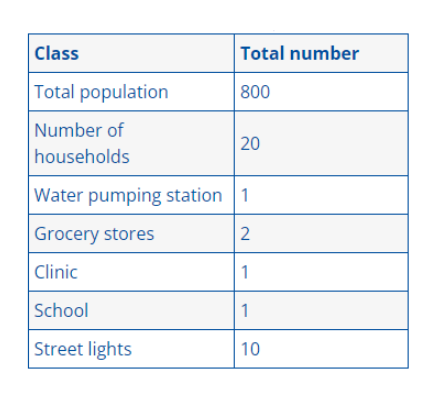

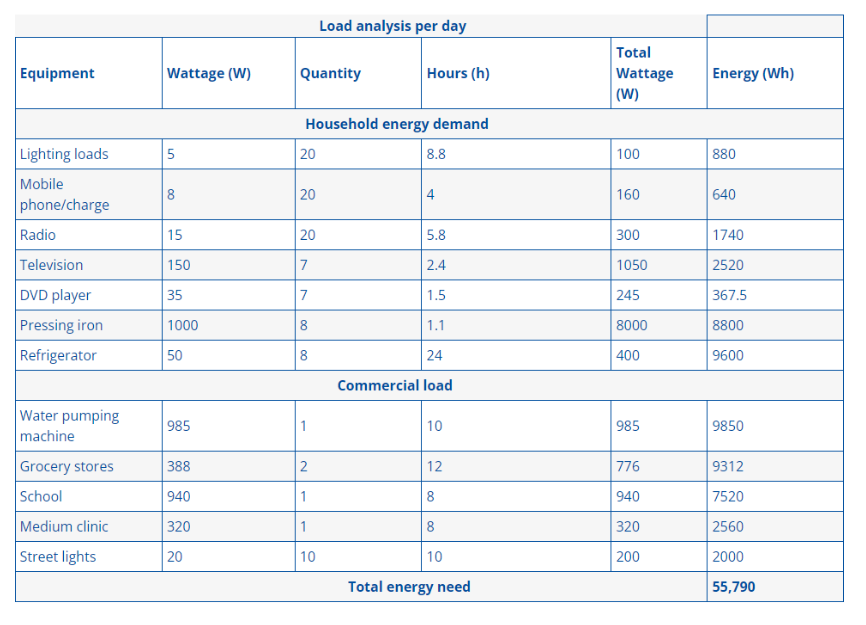

Data on Household Energy for Siwa Oasis:

Activities:

- Analyse typical household appliances and their power consumption (lighting, refrigeration, pressing Iron).

- Simulate daily energy usage patterns using smart meter data.

- Identify peak usage times and propose strategies for energy conservation (example LED bulbs, etc)

- Calculate appliance power consumption and estimate electricity costs.

- Discussion:

a. How does this situation relate to SDG 7, and why is it essential for sustainable development?

b. What are the primary and secondary challenges of implementing off-grid solutions in remote villages?

Part two: Power supply options

Electricity supply in Siwa Oasis is mainly depends on Diesel Generators, 4 MAN Diesel Generators of 21 MW which are going to be wasted in four years, 2 CAT Diesel Generators of 5.2 MW and 1 MAN Diesel Generator 4 MW for emergency. Compare and contrast various power supply options for the household (renewable vs. fossil fuel).

- Renewable: Focus on solar PV systems, including hands-on activities like solar panel power output measurements and battery sizing calculations.

- Fossil fuel: Briefly discuss diesel generators and their environmental impact.

The Siwa Oasis community is divided over the choice of power supply options for their households. On one hand, there is a group advocating for a complete shift to renewable energy, emphasising the environmental benefits and long-term sustainability of solar PV systems. On the other hand, there is a faction arguing to continue relying on the existing diesel generators, citing concerns about the reliability and initial costs associated with solar power. The community must decide which power supply option aligns with their values, priorities, and long-term goals for sustainability and energy independence. This decision will not only impact their day-to-day lives but also shape the future of energy use in Siwa Oasis.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

- Debate: Is it ethical to impose new technologies on communities, even if it’s for perceived improvement of living conditions?

- Discussion: How can engineers ensure the sustainability (environmental and operational) of off-grid solutions in remote locations?

- Activities: Students to design a basic solar PV system for the household, considering factors like energy demand, solar resource availability, and budget constraints.

Part three: Community mini-grid via harnessing the desert sun

Mini-grid systems (sometimes referred to as micro-grids) generally serve several buildings or entire communities. The abundant sunshine in Siwa community makes it ideal for solar photovoltaic (PV) systems and based on the load demand of the community, a solar PV mini grid solution will work perfectly.

Electrical components of a typical PV system can be classified into DC and AC.

DC components: The electrical connection of solar modules to the inverter constitutes the DC part of a PV installation. Its design requires particular care and reliable components, as there is a risk of significant accidents with high DC voltages and currents, especially due to electric arcs.

The key DC components are:

- PV cables and connectors: PV modules are usually delivered with a junction box and pre-assembled cables with single-contact electrical connectors. They enable easy interconnection of individual modules in strings. Solar cables are made of copper or aluminum (more cost-efficient).

- Combiner boxes: Here, incoming strings are connected in parallel, and the resulting current is channeled through an output terminal to the inverter. A combiner box usually contains all required protection devices, disconnectors, and measuring equipment for string monitoring.

AC components: The equipment installed on the AC side of the inverter depends on the size and voltage class of the grid connection (low-voltage (LV), medium-voltage (MV), or high-voltage (HV) grid). Utility-scale PV plants usually require the following equipment:

- Transformers, to increase the inverter output voltage to the grid voltage level

- AC cables, buried

- Circuit breakers, switchgears, and protection devices, for large PV plants (MV/HV connection)

- Electricity meters

Activities:

- Research and discuss the safety precautions and regulations for working with DC systems.

- Analyse the DC components of a typical PV system, including cables, connectors, and combiner boxes.

- Calculate the voltage and current levels at different points in the DC circuit based on the system design.

- Investigate the concept of power factor and its significance in grid stability and energy bills.

- Analyse the power factor of common household appliances and discuss its impact on the mini-grid.

- Propose strategies to improve the overall power factor of the mini-grid, such as using capacitors or choosing energy-efficient appliances.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.