Authors: Dr Homeira Shayesteh (Senior Lecturer/Programme Leader for Architectural Technology, Design Engineering & Mathematics Department, Faculty of Science & Technology, Middlesex University), Professor Jarka Glassey (Director of Education, School of Engineering, Newcastle University).

Topic: How to integrate the SDGs using a practical framework.

Type: Guidance.

Relevant disciplines: Any.

Keywords: Accreditation and standards; Assessment; Global responsibility; Learning outcomes; Sustainability; AHEP; SDGs; Curriculum design; Course design; Higher education; Pedagogy.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

Related SDGs: SDG 4 (Quality education); SDG 13 (Climate action).

Who is this article for? This article should be read by educators at all levels of higher education looking to embed and integrate sustainability into curriculum, module, and / or programme design.

Premise:

The critical role of engineers in developing sustainable solutions to grand societal challenges is undisputable. A wealth of literature and a range of initiatives supporting the embedding of sustainability into engineering curricula already exists. However, a practicing engineering educator responsible for achieving this embedding would be best supported by a practical framework providing a step-by-step guide with example resources for either programme or module/course-level embedding of sustainability into their practice. This practical framework illustrates a tested approach to programme wide as well as module alignment with SDGs, including further resources as well as examples of implementation for each step. This workflow diagram provides a visual illustration of the steps outlined below. The constructive alignment tool found in the Ethics Toolkit may also be adapted to a Sustainability context.

For programme-wide alignment:

1. Look around. The outcome of this phase is a framework that identifies current and future requirements for programme graduates.

a. Review guidelines and subject/discipline benchmark documents on sustainability.

b. Review government targets and discipline-specific guidance.

c. Review accreditation body requirements such as found in AHEP4 and guidance from professional bodies. For example, IChemE highlights the creation of a culture of sustainability, not just a process of embedding the topic.

d. Review your university strategy relating to sustainability and education. For example, Middlesex University signed up to the UN Accord.

e. Consider convening focus groups with employers in general and some employers of course alumni in particular. Carefully select attendees to represent a broad range of employers with a range of roles (recruiters, managers, strategy leaders, etc.). Conduct semi-structured focus groups, opening with broad themes identified from steps a through d. Identify any missing knowledge, skills, and competencies specific to particular employers, and prioritize those needed to be delivered by the programme together with the level of competency required (aware, competent, or expert).

2. Look back. The outcome of this phase is a programme map (see appendix) of the SDGs that are currently delivered and highlighting gaps in provision.

b. Conduct a SWOT analysis as a team, considering the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the programme from the perspective of sustainability and relevance/competitiveness.

c. Convene an alumni focus group to identify gaps in current and previous provision, carefully selecting attendees to represent a broad range of possible employment sectors with a range of experiences (fresh graduates to mid-career). Conduct semi-structured discussions opening with broad themes identified from steps 1a-e. Identify any missing knowledge, skills, and competencies specific to particular sectors, and those missing or insufficiently delivered by the programme together with the level of competency required (aware, competent, or expert).

d. Convene a focus group of current students from various stages of the programme. Conduct semi-structured discussions opening with broad themes identified from steps 1a-e and 2a-c. Identify student perceptions of knowledge, skills, and competencies missing from the course in light of the themes identified.

e. Review external examiner feedback, considering any feedback specific to the sustainability content of the programme.

3. Look ahead. The goal of this phase is programme delivery that is aligned with the SDGs and can be evidenced as such.

a. Create revised programme aims and graduate outcomes that reflect the SDGs. The Reimagined Degree Map and Global Responsibility Competency Compass can support this activity.

b. Revise module descriptors so that there are clear linkages to sustainability competencies or the SDGs generally within the aims of the modules.

c. Revise learning outcomes according to which SDGs relate to the module content, projects or activities. The Reimagined Degree Map and the Constructive Alignment Tool for Ethics provides guidance on revising module outcomes. An example that also references AHEP4 ILOS is:

- “Apply comprehensive knowledge of mathematics, biology, and engineering principles to solve a complex bioprocess engineering challenge based on critical awareness of new developments in this area. This will be demonstrated by designing solutions appropriate within the health and safety, diversity, inclusion, cultural, societal, environmental, and commercial requirements and codes of practice to minimise adverse impacts (M1, M5, M7).”

d. Align assessment criteria and rubrics to the revised ILOs.

e. Create an implementation plan with clear timelines for module descriptor approvals and modification of delivery materials.

For module-wide alignment:

1. Look around. The outcome of this phase is a confirmed approach to embedding sustainability within a particular module or theme.

a. Seek resources available on the SDGs and sustainability teaching in this discipline/theme. For instance, review these examples for Computing, Chemical Engineering and Robotics.

b. Determine any specific guidelines, standards, and regulations for this theme within the discipline.

2. Look back. The outcome of this phase is a module-level map of SDGs currently delivered, highlighting any gaps.

a. Engage in critical reflective analysis of current modules, as both individual module instructors and leaders, and as a team.

b. Conduct a SWOT analysis as a module team that considers the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the module from the perspective of sustainability and relevance of the module to contribute to programme-level delivery on sustainability and/or the SDGs.

c. Review feedback from current students on the clarity of the modules links to the SDGs.

d. Review feedback from external examiners on the sustainability content of the module.

3. Look ahead.

a. Create introduction slides for the modules that explicitly reference how sustainability topics will be integrated.

b. Embed specific activities involving the SDGs in a given theme, and include students in identifying these. See below for suggestions, and visit the Teaching resources in this toolkit for more options.

Appendix:

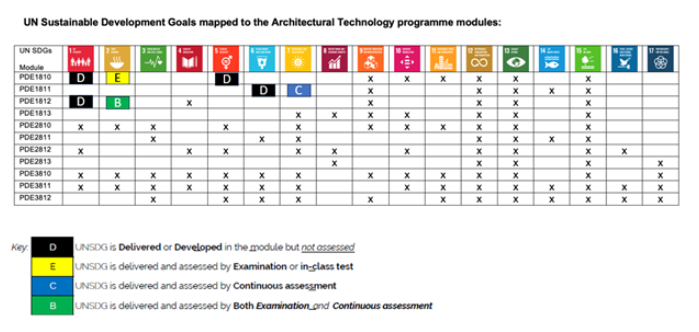

A. Outcome I.2 (programme level mapping)

B. Outcome II.5 (module level mapping) – same as above, but instead of the modules in individual lines, themes delivered within the module can be used to make sure the themes are mapped directly to SDGs.

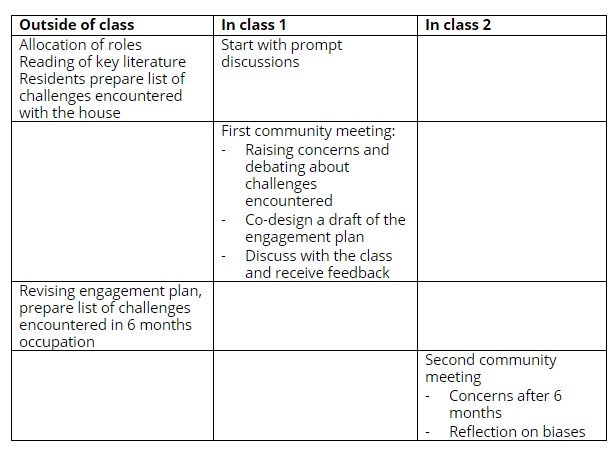

C. II.6.b – Specific activities

- Activity 1: Best carried out at the start of the module and then repeated near the end of the module to compare students perception and learning. Split students into groups of 3-4, at the start of the module use the module template (attached as a resource) to clearly outline the ILOs. Then present the SDGs and ask students to spend no more than 5 min identifying the top 3 SDGs they believe the material delivered in the module will enable them to address. Justify the selection. Can either feed back or exchange ideas with the group to their right. Capture these SDGs for comparison of the repeat exercise towards the end of the module. How has the perception of the group changed following the delivery of the module and why?

- Activity 2: Variation on the above activity – student groups to arrange the SDGs in a pyramid with the most relevant ones at the top, capture the picture and return to it later in module delivery

- Activity 3: Suitable particularly for the earlier stages. Use https://go-goals.org/ to increase the general awareness of SDGs.

- Activity 4: The coursework geared to the SDGs, with each student choosing a goal of their choice and developing a webmap to demonstrate the role of module-relevant data and analysis in tackling that goal.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.