Author: Dr J.L. Rowlandson (University of Bristol).

Author: Dr J.L. Rowlandson (University of Bristol).

Topic: Home heating in the energy transition.

Engineering disciplines: Chemical; Civil; Mechanical; Energy.

Ethical issues: Sustainability; Social responsibility.

Professional situations: Public health and safety; Conflicts of interest; Quality of work; Conflicts with leadership/management; Legal implication.

Educational level: Intermediate.

Educational aim: Becoming Ethically Sensitive: being broadly cognizant of ethical issues and having the ability to see how these issues might affect others.

Learning and teaching notes:

This case study considers not only the environmental impacts of a clean technology (the heat pump) but also the social and economic impacts on the end user. Heat pumps form an important part of the UK government’s net-zero plan. Our technical knowledge of heat pump performance can be combined with the practical aspects of implementing and using this technology. However, students need to weigh the potential carbon savings against the potential economic impact on the end user, and consider whether current policy incentivises consumers to move towards clean heating technologies.

This case study offers students an opportunity to practise and improve their skills in making estimates and assumptions. It also enables students to learn and practise the fundamentals of energy pricing and link this to the increasing issue of fuel poverty. Fundamental thermodynamics concepts, such as the second law, can also be integrated into this study.

This case study addresses two of the themes from the Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this case study to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

The dilemma in this case is presented in six parts. If desired, a teacher can use the Summary and Part one in isolation, but Parts two to six develop and complicate the concepts presented in the Summary and Part one to provide for additional learning. The case study allows teachers the option to stop at multiple points for questions and/or activities, as desired.

Learners have the opportunity to:

- understand how the current energy system works;

- relate the implementation of new technologies to real-world impacts on the consumer;

- improve their zeroth order approximation skills and use these back of the envelope calculations to inform decisions;

- consider how to weigh the benefits and burdens of ethical decisions;

- consider the influence of policy on technology uptake and consumer behaviour.

Teachers have the opportunity to:

- introduce concepts related to energy pricing;

- integrate technical content about energy and thermodynamics;

- informally evaluate students’ research skills and zeroth order approximation.

Learning and teaching resources:

Open access textbooks:

- Applications of Thermodynamics – Heat Pumps & Refrigerators

- Chapter 2: The LCA Textbook (excellent resource for back of the envelope estimation methods)

Journal articles:

Educational institutions:

Business:

Government reports:

Other organisations:

- Guide to Energy Performance Certificates

- Energy Performance Certificates Explained

- Electrification of Heat Project

- Defining net zero for social housing: discussion paper

Stakeholder mapping:

- Stakeholder mapping: a complete guide with examples

- Stakeholder mapping & analysis template

- Stakeholder mapping 101

Summary – Heating systems and building requirements:

You are an engineering consultant working for a commercial heat pump company. The company handles both the manufacture and installation of heat pumps. You have been called in by a county council to advise and support a project to decarbonise both new and existing housing stock. This includes changes to social housing (either directly under the remit of the council or by working in partnership with a local housing association) and also to private housing, encouraging homeowners and landlords to move towards net zero emissions. In particular, the council is interested in the installation of clean heating technologies with a focus on heat pumps, which it views as the most technologically-ready solution. Currently most heating systems rely on burning natural gas in a boiler to provide heat. By contrast, a heat-pump is a device that uses electricity to extract heat from the air or ground and transfer it to the home, avoiding direct emission of carbon dioxide.

The council sets your first task of the project as assessing the feasibility of replacing the existing gas boiler systems with heat pumps in social housing. You are aware that there are multiple stakeholders involved in this process you need to consider, in addition to evaluating the suitability of the housing stock for heat pump installation.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

1. Discussion: Why might the council have prioritised retrofitting the social housing stock with heat pumps as the first task of the project? How might business and ethical concerns affect this decision?

2. Activity: Use stakeholder mapping to determine who are the main stakeholders in this project and what are their main priorities? In which areas will these stakeholders have agreements or disagreements? What might their values be, and how do those inform priorities?

3. Discussion: What key information about the property is important for choosing a heating system? What does the word feasibility mean and how would you define it for this project?

4. Activity: Research the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC): what are the main factors that determine the energy performance of a building?

5. Discussion: What do you consider to be an ‘acceptable’ EPC rating? Is the EPC rating a suitable measure of energy efficiency? Who should decide, and how should the rating be determined?

Technical pre-reading for Part one:

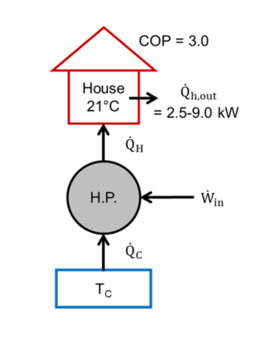

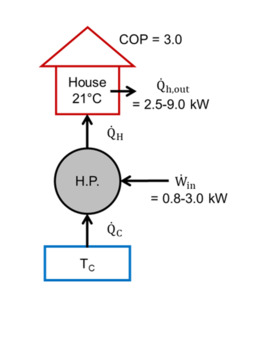

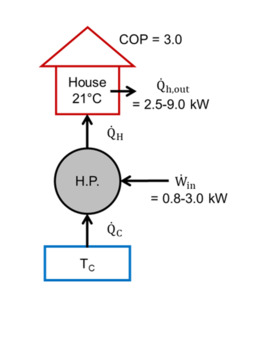

It is useful to introduce the thermodynamic principles on which heat pumps operate in order to better understand the advantages and limitations when applying this engineering technology in a real-world situation. A heat pump receives heat (from the air, ground, or water) and work (in the form of electricity to a compressor) and then outputs the heat to a hot reservoir (the building you are heating). We recommend covering:

- the second law of thermodynamics and how a heat pump works;

- the coefficient of performance (COP).

An online, open-source textbook that covers both topics is Applications of Thermodynamics – Heat Pumps & Refrigerators.

Dilemma – Part one – Considering heat pump suitability:

You have determined who the main stakeholders are and how to define the project feasibility. A previous investigation commissioned by the council into the existing housing stock, and one of the key drivers for them to initiate this project, has led them to believe that most properties will not require significant retrofitting to make them suitable for heat pump installation.

Optional STOP for question and activities:

1. Activity: Research how a conventional gas boiler central heating system works. How does a heat pump heating system differ? What heat pump technologies are available? What are the design considerations for installing a heat pump in an existing building?

Dilemma – Part two – Inconsistencies:

You spot some inconsistencies in the original investigation that appear to have been overlooked. On your own initiative, you decide to perform a more thorough investigation into the existing housing stock within the local authority. Your findings show that most of the dwellings were built before 1980 and less than half have an EPC rating of C or higher. The poor energy efficiency of the existing housing stock causes a potential conflict of interest for you: there are a significant number of properties that would require additional retrofitting to ensure they are suitable for heat pump installation. Revealing this information to the council at this early stage could cause them to pull out of the project entirely, causing your company to lose a significant client. You present these findings to your line manager who wants to suppress this information until the company has a formal contract in place with the council.

Optional STOP for question and activities:

1. Discussion: How should you respond to your line manager? Is there anyone else you can go to for advice? Do you have an obligation to reveal this information to your client (the council) when it is they who overlooked information and misinterpreted the original study?

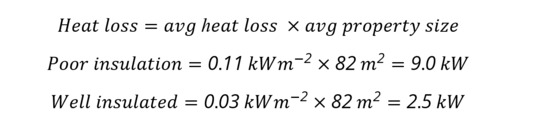

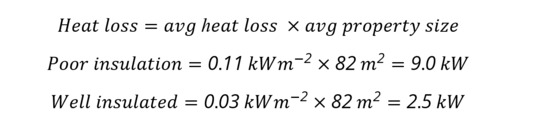

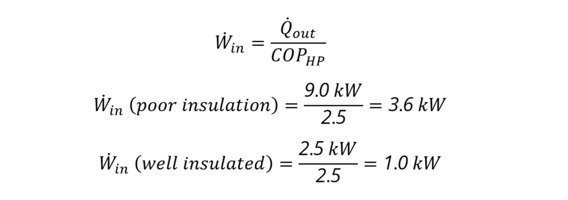

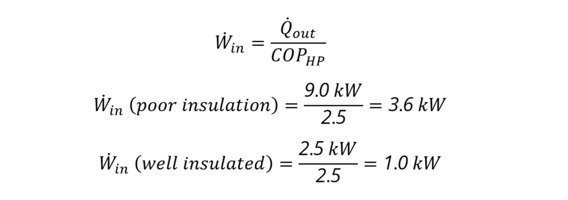

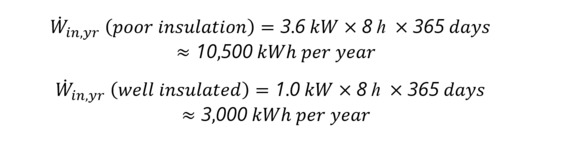

2. Activity: An example of a factor that causes a poor EPC rating is how quickly the property loses heat. A common method for significantly reducing heat loss in a home is to improve the insulation. Estimate the annual running cost of using an air-source heat pump in a poorly-insulated versus a well-insulated home to look at the potential financial impact for the tenant (example approach shown in the Appendix, Task A).

3. Discussion: What recommendations would you make to the council to ensure the housing is heat-pump ready? Would your recommendation change for a new-build property?

Dilemma – Part three – Impact of energy costs on the consumer:

Your housing stock report was ultimately released to the council and they have decided to proceed, though for a more limited number of properties. The tenants of these dwellings are important stakeholders who are ultimately responsible for the energy costs of their properties. A fuel bill is made up of the wholesale cost of energy, network costs to transport it, operating costs, taxes, and green levies. Consumers pay per unit of energy used (called the unit cost) and also a daily fixed charge that covers the cost of delivering energy to a home regardless of the amount of energy used (called the standing charge). In the UK, currently the price of natural gas is the main driver behind the price of electricity; the unit price of electricity is typically three to four times the price of gas.

Your next task is to consider if replacing the gas boiler in a property with a heat pump system will have a positive or negative effect on the running costs.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

1. Activity: Estimate the annual running cost for a property when using a heat pump versus a natural gas boiler (see Appendix Task B for an example approach).

2. Discussion: Energy prices are currently rising and have seen drastic changes in the UK over the past year. The lifetime of a new heat pump system is around 20 years. How would rising gas and electric prices affect the tenant? Does this impact the feasibility of using a gas boiler versus a heat pump? How can engineering knowledge and expertise help inform pricing policies?

Dilemma – Part four – Tenants voice concerns:

After a consultation, some of the current tenants whose homes are under consideration for heat pump installation have voiced concerns. The council is planning to install air-source heat pumps due to their reduced capital cost compared to a ground-source heat pump. The tenants are concerned that the heat pump will not significantly reduce their fuel bills in the winter months (when it is most needed) and instead could increase their bills if the unit price and standing charge for electricity continue to increase. They want a guarantee from the council that their energy bills will not be adversely affected.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

1. Discussion: Why would air-source heat pumps be less effective in winter? What are the potential effects of increased energy bills on the tenants? How much input should the tenants have on the heating system in their rented property?

2. Discussion: Do the council have any responsibility if the installation does result in an increased energy bill in the winter for their tenants? Do you and your company have any responsibility to the tenants?

Dilemma – Part five – The council consultation:

The council has hosted an open consultation for private homeowners within the area that you are involved in. They want to encourage owners of private dwellings to adopt low-carbon technologies and are interested in learning about the barriers faced and what they can do to encourage the adoption of low carbon-heating technologies. The ownership of houses in the local area is similar to the overall UK demographic: around 20% of dwellings are in the social sector (owned either by the local authority or a housing association), 65% are privately owned, and 15% are privately rented.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

1. Activity: Estimate the lifetime cost of running an air-source heat pump and ground-source heat pump versus a natural gas boiler. Include the infrastructure costs associated with installation of the heating system (see Appendix Task C for an example approach). This can be extended to include the impact of increasing energy prices.

2. Activity: Research the policies, grants, levies, and schemes available at local and national levels that aim to encourage uptake of net zero heating.

3. Discussion: From your estimations and research, how suitable are the current schemes? What recommendations would you make to improve the uptake of zero carbon heating?

Dilemma – Part six – Recommendations:

Energy costs and legislation are important drivers for encouraging homeowners and landlords to adopt clean heating technologies. There is a need to weigh up potential cost savings with the capital cost associated with installing a new heat system. Local and national policies, grants, levies, and bursaries are examples of tools used to fund and support adoption of renewable technologies. Currently, an environmental and social obligations cost, known as the ‘green levies,’ are added to energy bills which contribute to a mixture of social and environmental energy policies (including, for example, renewable energy projects, discounts for low-income households, and energy efficiency improvements).

Your final task is to think more broadly on encouraging the uptake of low-carbon heating systems in private dwellings (the majority of housing in the UK) and to make recommendations on how both councils locally and the government nationally can encourage uptake in order to reduce carbon emissions.

Optional STOP for questions and activities:

1. Discussion: In terms of green energy policy, where does the ethical responsibility lie – with the consumer, the local government, or the national government?

2. Discussion: Should the national Government set policies like the green levy that benefit the climate in the long-term but increase the cost of energy now?

3. Discussion: As an employee of a private company, to what extent is the decarbonisation of the UK your problem? Do you or your company have a responsibility to become involved in policy? What are the advantages or disadvantages to yourself as an engineer?

Appendix:

The three tasks that follow are designed to encourage students to practise and improve their zeroth order approximation skills (for example a back of the envelope calculation). Many simplifying assumptions can be made but they should be justified.

Task A: Impact of insulation

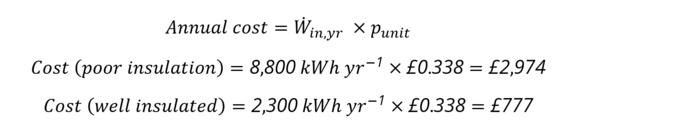

Challenge: Estimate the annual running cost for an air-source heat pump in a poorly insulated home. Compare to a well-insulated home.

Base assumptions around the heat pump system and the property being heated can be researched by the student as a task or given to them. In this example we assume:

- The air source heat-pump has a COP of 2.5

- The air-source heat pump runs for 8 hours a day to maintain a temperature of 21 °C

- The average UK property size is 82 m2

- A poorly insulated property (Victorian, single-glazed, no loft insulation) has an average heat loss of 110 W/m2

- A well-insulated property (recent new build, post-2006) has an average heat loss of 30 W/m2

- The unit price of electricity is 33.8 p per kWh

Example estimation:

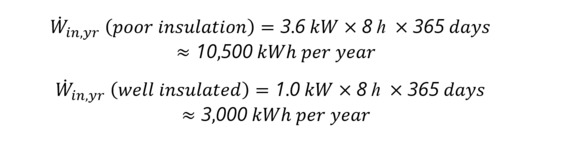

1. Estimate the overall heat loss for a poorly- and well-insulated property.

Note: heat loss is greater in the poorly insulated building.

2. Calculate the work input for the heat pump.

Assumption: heat pump matches the heat loss to maintain a consistent temperature.

Note: a higher work input is required in the poorly insulated building to maintain a stable temperature.

3. Determine the work input over a year.

Assumption: heat pump runs for 8 hours per day for 365 days.

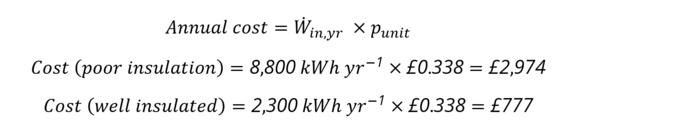

4. Determine the running cost

For an electricity unit price of 33.8 p per kWh.

Note: running cost is higher for the poorly insulated building due to the higher work input required to maintain temperature.

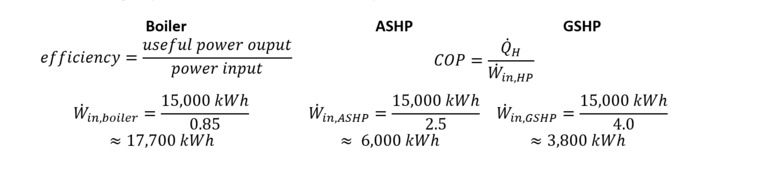

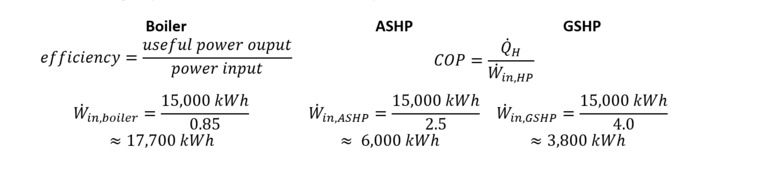

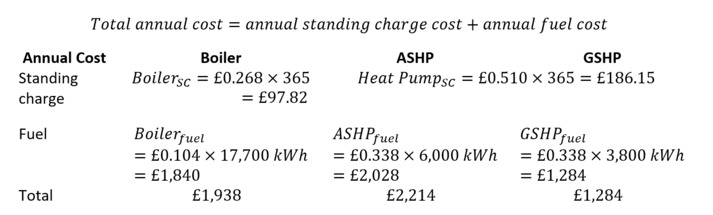

Task B: Annual running cost estimation

Challenge: Estimate the annual running cost for a property when using a heat pump versus a natural gas boiler.

Base assumptions around the boiler system, heat pump system, and property can be researched by the student as a task or given to them. In this example we assume:

- The building requires 15,000 kWh for heating every year

- A boiler has an efficiency of 85 %

- An air-source heat pump (ASHP) has a COP of 2.5

- A ground-source heat pump (GSHP) has a COP of 4.0

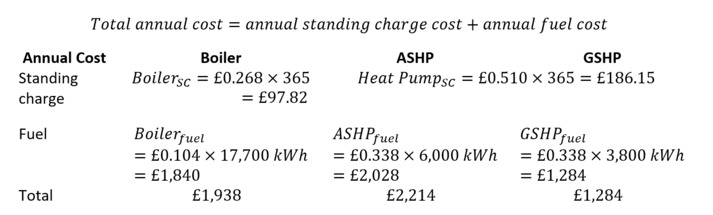

Energy tariffs (correct at time of writing) for the domestic consumer including the energy price guarantee discount:

| Domestic energy tariffs | |

| Electric standing charge | 51.0p per day |

| Unit price of electricity | 33.8p per kWh |

| Gas standing charge | 26.8p per kWh |

| Unit price of gas | 10.4p per kWh |

Example estimation:

1. Calculate the annual power requirement for each case.

Assumed heating requirement is 15,000 kWh for the year.

2. Calculate the annual cost for each case:

Note: the higher COP of the ground-source heat pump makes this the more favourable option (dependent on the fuel prices).

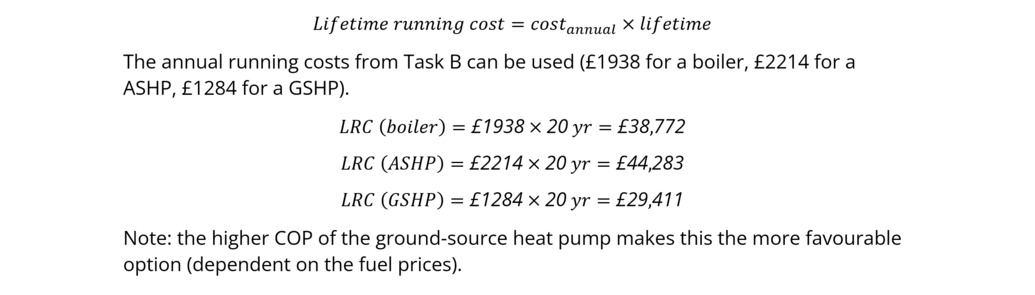

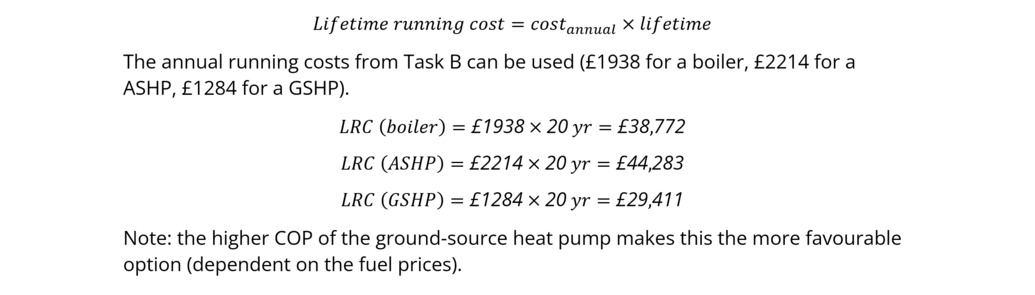

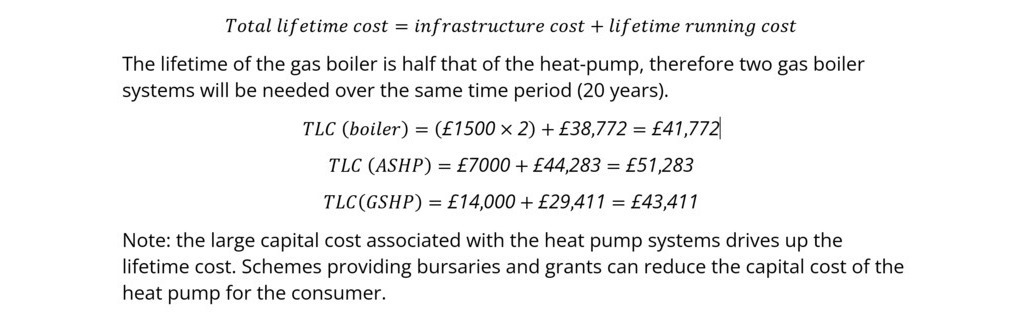

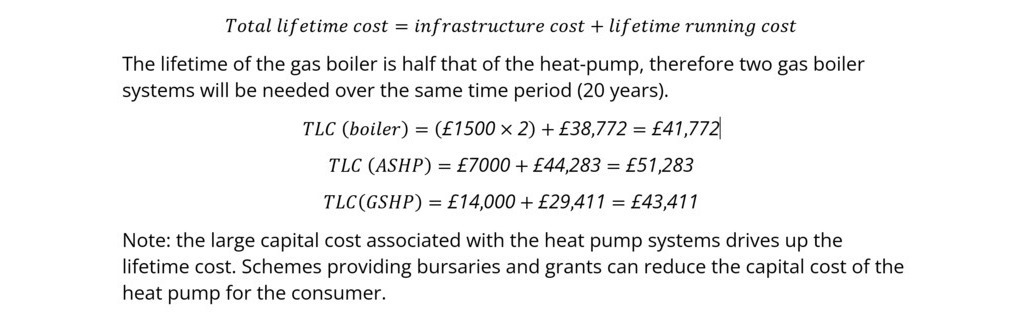

Task C: Lifetime cost estimation

Challenge: Estimate the total lifetime cost for a property when using a heat pump versus a natural gas boiler.

Base assumptions around the boiler system, heat pump system, and property can be researched by the student as a task or given to them. In this example we assume:

- Identical assumptions to Task B on the heating requirement (15,000 kWh), boiler efficiency (85%), and heat pump COP (2.5 for air-source and 4.0 for ground-source)

- The average boiler lifetime is 10 years

- The average heat pump lifetime (air-source and ground source) is 20 years

- The infrastructure cost for boiler installation is £1,500, for an ASHP is £7,000, and for a GSHP is £14,000

Energy tariffs (correct at time of writing) for the domestic consumer including the energy price guarantee discount:

| Domestic energy tariffs | |

| Electric standing charge | 51.0p per day |

| Unit price of electricity | 33.8p per kWh |

| Gas standing charge | 26.8p per kWh |

| Unit price of gas | 10.4p per kWh |

1. Calculate the lifetime running cost for each case.

2. Calculate the total lifetime cost for each case.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.