Case study example: Water wars: managing competing water rights

Activity: Assessment. This example demonstrates how the questions provided in Assessing ethics: Rubric can be used to assess the competencies stipulated at each level.

Authors: Dr. Natalie Wint (UCL); Dr. William Bennett (Swansea University).

Related content:

- Assessing ethics: Guidance & rubric

- Case study: Water wars: managing competing water rights

- Methods for assessing and evaluating ethics learning in engineering education

Water wars: managing competing water rights

This example demonstrates how the questions provided in the accompanying rubric can be used to assess the competencies stipulated at each level. Although we have focused on ‘Water Wars’ here, the suggested assessment questions have been designed in such a way that they can be used in conjunction with the case studies available within the toolkit, or with another case study that has been created (by yourself or elsewhere) to outline an ethical dilemma.

Year 1

Personal values: What is your initial position on the issue? Do you see anything wrong with how DSS are using water? Why, or why not?

- Students should provide a stance, but more importantly their stance should be justified. In this instance this may involve reference to common moral values such as environmental sustainability, risk associated with power issues and questions of ownership.

Professional responsibilities: What ethical principles and codes of conduct are relevant to this situation?

- Students should refer to relevant principles (e.g. from the Joint Statement of Ethical Principles). For example, in this case some of the relevant principles may include (but not be limited to) “protect, and where possible improve, the quality of built and natural environment”, “maximise the public good and minimise both actual and potential adverse effects for their own and succeeding generations” and “take due account of the limited availability of natural resources”.

Ethical principles and codes of conduct can be used to guide our actions during an ethical dilemma. How does the guidance provided in this case align/differ with your personal views? (This is a question we had created in addition to those provided within the case study to meet the requirements stipulated in the accompanying rubric.)

- Students’ answers will depend upon those given to the previous questions but should include some discussion of similarities and differences between their own initial thoughts and principles/codes of conducts, and allude to the tensions involved in ethical dilemmas and the impact on decision making.

What are the moral values involved in this case and why does it constitute an ethical dilemma? (This is a question we had created in addition to those provided within the case study to meet the requirements stipulated in the accompanying rubric.)

- Students should be able to identify relevant moral values and explain that an ethical dilemma constitutes a problem in which two or more moral values or norms cannot be fully realised at the same time.

- There are two (or a limited number of) options for action and whatever they choose they will commit a moral wrong. The crucial feature of a moral dilemma is not the number of actions that are available but the fact that all possible actions are morally unsatisfactory.

What role should an engineer play in influencing the outcome? What are the implications of not being involved? (This is a question we had created in addition to those provided within the case study to meet the requirements stipulated in the accompanying rubric.)

- Engineers are responsible for the design of technological advancements which necessitate data storage. Although this brings many benefits, engineers need to consider the adverse impact of technological advancement such as increased water use. Students may therefore want to consider the wider implications of data storage on the environment and how these can be mitigated.

Year 2

Formulate a moral problem statement which clearly states the problem, its moral nature and who needs to act. (This is a question we had created in addition to those provided within the case study to meet the requirements stipulated in the accompanying rubric.)

- An example could be: “Should the civil engineer working for DSS remain loyal to the company and defend them against accusations of causing environmental hazards, or defend their water rights and say that they will not change their behaviour”. It should be clear what the problem is, the moral values at play and who needs to act.

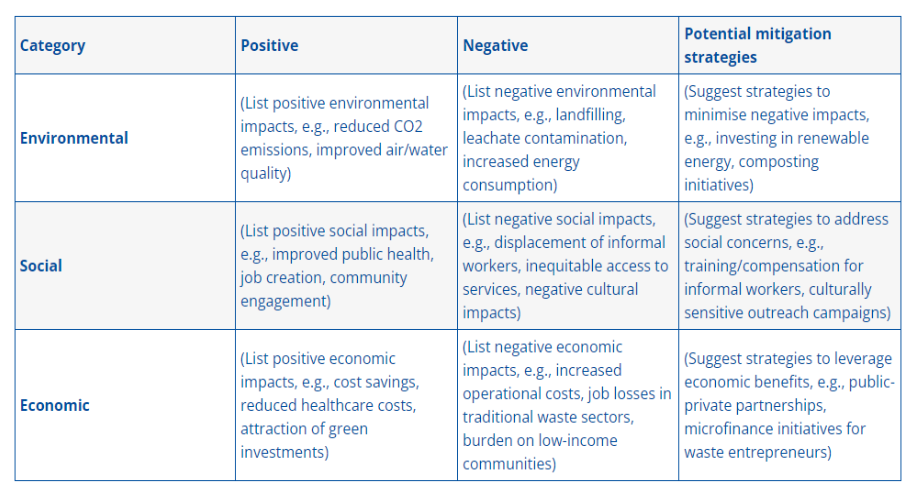

Stakeholder mapping: Who are all the stakeholders in the scenario? What are their positions, perspective and moral values?

- Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of the relevant stakeholders and values that may come up.

| Stakeholder | Perspectives/interests | Moral values |

| Data Storage Solutions (DSS) | Increasing production in a profitable way; meeting legal requirements; good reputation to maintain/grow customer base. | Accountability; sustainability (primarily economic). |

| Farmers’ union | Represent farmers who suffer from economic implications associated with costly irrigation. | Accountability; environmental sustainability; justice. |

| Farm | The farm (presumably) benefits from DSS using the land. | Ownership and property; environmental sustainability; justice. |

| Local Green Party | Represent views of those concerned about biodiversity. May be interested in opening of green battery plant. | Human welfare; environmental sustainability; justice. |

| Local Council | Represent views of all stakeholders and would need to consider economic benefits of DSS (tax and employment), the need of the university and hospital, as well as the needs of local farmers and environmentalists. May be interested in opening of green battery plant. | Human welfare and public health; trust; accountability; environmental sustainability; justice. |

| Member of the public | This may depend on their beliefs as an individual, their employment status and their use of services such as the hospital and university. Typically interested in low taxes/responsible spending of public money. May be interested in opening of green battery plant. | Human welfare; trust; accountability; environmental sustainability; justice. |

| Stakeholders using DSS data storage | Reliable storage. They may also be interested in being part of an ethical supply chain. | Trust; privacy; accountability; autonomy. |

| Non-human stakeholders | Environmental sustainability. |

What are some of the possible courses of action in the situation. What responsibilities do you have to the various stakeholders involved? What are some of the advantages and disadvantages associated with each? (Reworded from case study.)

- Students should provide a stance but may recognise the tensions involved. For example, at a micro level, tensions between loyalty to the profession and loyalty to the company/personal financial stability. Responsibilities to fellow employees may include the degree to which you risk their jobs by being honest. They may also feel that they should protect environmental and natural resources.

- At a macro level, they may consider the need for engineers to inform decisions regarding issues that engineering and technology raise for society (e.g. increased water being needed for data storage) and listen to the aspirations and concerns of others, and challenging statements or policies that cause them professional concern.

What are the relevant facts in this scenario and what other information would you like to help inform your ethical decision making? (This is a question we had created in addition to those provided within the case study to meet the requirements stipulated in the accompanying rubric.)

- Students should identify which facts within the case study are relevant in terms of making an ethical decision. In this case, some of the relevant facts may include:

-

- Water use permissible by law (“the data centre always uses the maximum amount legally allotted to it.”)

-

- This centre manages data which is vital for the local community, including the safe running of schools and hospitals, and that its operation requires sufficient water for cooling.

-

- In more arid months, the nearby river almost runs dry, resulting in large volumes of fish dying.

-

- Water levels in farmers’ wells have dropped, making irrigation much more expensive and challenging.

-

- A new green battery plant is planned to open nearby that will create more data demand and has the potential to further increase DSS’ water use.

-

- Obtaining water from other sources will be costly to DSS and may not be practically possible, let alone commercially viable.

- Students should be aware that incomplete information hinders decision making during ethical dilemmas, and that in some cases, further information will be needed to help inform decisions. In this case, some of the questions may pertain to:

-

- Exactly how much water is being used and the legal rights.

-

- Relationship between farmer and DSS/contractual obligations.

-

- How costly irrigation is to the farmers (economic impact), as well as the knock-on impact to their business and supply chain.

-

- How many people DSS employ and how important they are for local economy.

-

- Detail regarding biodiversity loss and its wider impact.

-

- How likely it is that the green battery plant will open and whether DSS is the only eligible supplier.

-

- How much the green battery plant contract is worth to DSS.

-

- How much water the green battery plant will use in the case that DSS get the contract.

-

- Whether DSS is the only option for hospital and university.

-

- What will happen if the services DSS provide to the hospital and university stop or becomes unreliable.

Year 2/Year 3

(At Year 2, students could provide options; at Year 3 they would evaluate and form a judgement.)

Make use of ethical frameworks and/or professional codes to evaluate the options for DSS both short term and long term. How do the uncertainty and assumptions involved in this case impact decision making?

- Students should list plausible options. They can then analyse them with respect to different ethical frameworks (whilst we don’t necessary make use of normative ethical theories, analysis according to consequences, intention or action may be a useful approach to this). Below we have included a non-exhaustive list of options with ideas in terms of analysis.

| Option | Consequences | Intention | Action |

| Keep using water | May lead to expansion and profit of DSS and thus tax revenue/employment and supply.

Reputational damage of DSS may increase. Individual employee piece of mind may be at risk. Farmers still don’t have water and biodiversity still suffers which may have further impact long term. |

Intention behind action not consistent with that expected by an engineer, other than with respect to legality | Action follows legal norms but not social norms such as good will and concern for others. |

| Keep using the water but limit further work | May limit expansion and profit of DSS and thus tax revenue/employment and supply.

Farmers still don’t have water and biodiversity still suffers and may have further impact long term. This could still result in reputation damage. |

Intention behind action partially consistent with that expected by an engineer. | Action follows legal norms but only partially follow social norms such as good will and concern for others. |

| Make use of other sources of water | Data storage continues.

Potential for reputation to increase. Potential increase in cost of water resulting in less profit potentially less tax revenue/employment. Farmers have water and biodiversity may improve. Alternative water sources may be associated with the same issues or worse. |

Intention behind action seems consistent with that expected by an engineer. However, this is dependent upon

whether they chose to source sustainable water with less impact on biodiversity etc. |

This may be dependent on the degree to which DSS proactively source sustainable water. |

| Reduce work levels or shut down | Impact on profit and thus tax revenue/employment and supply chain. Farmers have water and biodiversity may improve.

May cause operational issues for those whose data is stored. |

Seems consistent with those expected of engineer. Raises questions more generally about viability and feasibility of data storage. | Action doesn’t follow social norms of responsibility to employees and shareholders. |

| Investigate other cooling methods which don’t require as much water/don’t take on extra work until another method identified. |

May benefit whole sector.

May cause interim loss of service.

|

This follows expectations of the engineering profession in terms of evidence-based decision making and consideration for impact of engineering in society. | It follows social norms in terms of responsible decision making. |

Downloads:

Assessing ethics: Case study assessment example: Water Wars

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.