Authors: Diana Adela Martin (University College London), Suleman Audu and Jeremy Mantingh (Engineers Without Borders The Netherlands).

Topic: Circular business models.

Tool type: Teaching.

Relevant disciplines: Chemical; Biochemical; Manufacturing.

Keywords: Circular business models; Teaching or embedding sustainability; Plastic waste; Plastic pollution; Recycling or recycled materials; Responsible consumption; Teamwork; Interdisciplinary; AHEP; Higher education.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

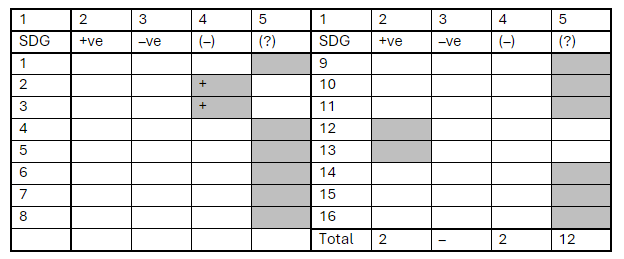

Related SDGs: SDG 4 (Quality education); SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities); SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production); SDG 13 (Climate action); SDG 14 (Life below water).

Educational level: Intermediate.

Learning and teaching notes:

This case study is focused on the role of engineers to address the problem of plastic waste in the context of sustainable operations and circular business solutions. It involves a team of engineers developing a start-up aiming to tackle plastic waste by converting it into infrastructure components (such as plastic bricks). As plastic waste is a global problem, the case can be customised by instructors when specifying the region in which it is set. The case incorporates several components, including stakeholder mapping, empirical surveys, risk assessment and policy-making. This case study is particularly suitable for interdisciplinary teamwork, with students from different disciplines bringing their specialised knowledge.

The case study asks students to research the data on how much plastic is produced and policies for the disposal of plastic, identify the regions most affected by plastic waste, develop a business plan for a circular business focused on transforming plastic waste into bricks and understand the risks of plastic production and waste as well as the risks of a business working with plastic waste. In this process, students gain an awareness of the societal context of plastic waste and the varying risks that different demographic categories are exposed to, as well as the role of engineers in contributing to the development of technologies for circular businesses. Students also get to apply their disciplinary knowledge to propose technical solutions to the problem of plastic waste.

The case is presented in parts. Part one addresses the broader context of plastic waste and could be used in isolation, but parts two and three further develop and add complexity to the engineering-specific elements of the topic.

Learners have the opportunity to:

- apply their ethical judgement to a case study focused on a circular technology;

- understand the national and supranational policy context related to the production and disposal of plastic;

- analyse engineering and societal risks related to the development of a novel technology;

- develop a business model for a circular technology dealing with plastic waste;

- identify the key stakeholder groups in the development of a circular business model;

- reflect on how risks may differ for different demographic groups and identify the stakeholder groups most vulnerable to the negative effects of plastic waste;

- develop an empirical survey to identify the risks that stakeholders affected by or working with plastic waste are exposed to;

- develop a risk assessment to identify the risks involved in the manufacturing of plastic waste bricks;

- provide recommendations for lowering the risks in the manufacturing of plastic bricks.

Teachers have the opportunity to include teaching content purporting to:

- Physico-chemical properties of plastic waste;

- Manufacturing processes of plastic products and plastic bricks;

- Sustainable policies targeting plastic usage and reduction;

- Climate justice;

- Circular entrepreneurship;

- Risk assessment tools such as HAZOP and their application in the chemical industry.

Recommended pre-reading:

Part one:

- The European Union on plastic waste

- United Nations Environment Programme on plastic pollution

- The World Bank: How is plastic waste linked to poverty and development?

- Tearfund report: Plastic pollution and poverty

- Guglielmi, G. (2017). ‘In the next 30 years, we’ll make four times more plastic waste than we ever have.’, Science.org.

Part two:

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (n.d.). Plastics and the circular economy.

- Thorton, A. (2019). These 11 companies are leading the way to a circular economy. World Economic Forum.

- The Great Plastic Bake Off. (n.d.). Project Ghana.

- Clark, D. & Spindler, W. (2020). Circular business models can unlock $4.5 trillion of economic value. Big ideas podcast.

Part one:

Plastic pollution is a major challenge. It is predicted that if current trends continue, by 2050 there will be 26 billion metric tons of plastic waste, and almost half of this is expected to be dumped in landfills and the environment (Guglielmi, 2017). As plastic waste grows at an increased speed, it kills millions of animals each year, contaminates fresh water sources and affects human health. Across the world, geographical regions are affected differently by plastic waste. In fact, developing countries are more affected by plastic waste than developed nations. Existing reports trace a link between poverty and plastic waste, making it a development problem. Africa, Asia and South America see immense quantities of plastic generated elsewhere being dumped on their territory. At the moment, there are several policies in place targeting the production and disposal of plastic. Several of the policies active in developed regions such as the EU do not allow the disposal of plastic waste inside their own territorial boundaries, but allow it on outside territories.

Optional STOP for activities and discussion

- Conduct research to identify 5 national or international regulations or policies about the use and disposal of plastic.

- Compare these policies by stating which is the issuing policy body, what is the aim and scope of the policy.

- Reflect on the effectiveness of each policy and debate in class what are the most effective policies you identified.

- Write a reflection piece based on a policy of your choice targeting the use or disposal of plastic. In this reflection, identify the benefits of the policy as well as potential limitations. You may consider how you would improve the policy.

- Conduct research to identify how much plastic is produced and how much plastic waste is generated in your region. Identify which sectors are the biggest producers of waste. Conduct research on how much of this plastic waste is being exported and where is it exported.

- Identify the countries and companies with the biggest plastic footprint. Discuss in the classroom what you consider to contribute to these rankings.

- Research global waste trading and identify the countries that are the biggest exporters and importers of plastic waste. Discuss the findings in classroom and what you consider to contribute to these rankings. Discuss whether there are or should be any restrictions governing global waste trade.

- Write a report analysing the plastic footprint of a country or company of your choice. Include recommendations for minimising the plastic footprint.

- Watch in class the documentary Plastic earth or A plastic ocean and discuss in class your key take-aways.

Part two:

Impressed by the magnitude of the problem of plastic waste faced today, together with a group of friends you met while studying engineering at the Technological University of the Future, you want to set up a green circular business. Circular business models aim to use and reuse materials for as long as possible, all while minimising waste. Your concern is to develop a sustainable technological solution to the problem of plastic waste. The vision for a circular economy for plastic rests on six key points (Ellen McArthur Foundation, n.d.):

- Elimination of problematic or unnecessary plastic packaging through redesign, innovation, and new delivery models is a priority

- Reuse models are applied where relevant, reducing the need for single-use packaging

- All plastic packaging is 100% reusable, recyclable, or compostable

- All plastic packaging is reused, recycled, or composted in practice

- The use of plastic is fully decoupled from the consumption of finite resources

- All plastic packaging is free of hazardous chemicals, and the health, safety, and rights of all people involved are respected

Optional STOP for group activities and discussion

- Read about the example of the Great Plastic Bake Off and their project focused on converting plastic waste into plastic bricks. Research the chemical properties of plastic bricks and the process for the manufacturing process. Present your findings on a poster or discuss it in class.

- Develop a concept map with ideas for potential sustainable technologies for reducing or recycling plastic waste. You may use as inspiration the Circular Strategies Scanner (available here).

- Select one idea that you want to propose as the focus of your sustainable start-up. Give a name to your startup!

- Describe the technology you want to produce: what is its aim? What problem can it solve or what gap can it address? What are the envisioned benefits of your technology? What are its key features?

- Map the key stakeholders of the technology, by identifying the decision-makers for this technology, the beneficiaries of the technology, as well as those who are exposed to the risks of the technology

- Analyse the market for your technology: are there businesses with a similar aim or similar technology? What differentiates your business or technology from them?

- Identify key policies relevant to your technology: are there any policies or regulations in place that you should consider? In your geographical area, are there any policy incentives for sustainable technologies or businesses similar to the one you are developing?

- For your start-up, assign different roles to the members of your group (such as technology officer, researcher, financial officer, communication manager, partnership director a.s.o) and describe the key tasks of each member. Identify how much personnel you would need

- Identify the cost components and calculate the yearly costs for running your business (including personnel).

- Perform a SWOT analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats for your business. You may use this matrix to brainstorm each component.

Part three:

The start-up SuperRecycling aims to develop infrastructure solutions by converting plastic waste into bricks. Your team of engineers is tasked to develop a risk assessment for the operations of the factory in which this process will take place. The start-up is set in a developing country of your choice that is greatly affected by plastic waste.

Optional STOP for group activities and discussion

- Agree on the geographical location of the startup SuperRecycling and identify the amount of plastic waste that your region has to cope with, as well as any other relevant socio-economic characteristics of the region.

- Identify the demographic categories that are most exposed to the risks of plastic waste in the region.

- Research and analyse the situation of the informal plastic waste picking sector in the region: who is picking up the waste? How much do they earn for working with waste? Is this a regular form of income and who pays this income? What does it mean to be an “informal” worker? Are there any key insights about the characteristics of the plastic waste workers that you find interesting?

- Based on research and your own reflections, write a report on the role and risks that the plastic waste pickers are exposed to in their work.

- Create an empirical survey with the aim of identifying the risks the plastic waste pickers are exposed to, as well as the strategies they take to mitigate risks or deal with accidents.

- Create an empirical survey with the aim of identifying the risks that the factory workers at SuperRecycling are exposed to, as well as the strategies they take to mitigate risks or deal with accidents.

- Research the manufacturing process for developing plastic bricks and analyse the technical characteristics of plastic bricks, based on existing tests.

- With the classroom split into 2 groups, argue in favour or against their use of plastic bricks in construction. One group develops 5 arguments for the use of plastic bricks in construction, while the other group develops 5 arguments against the use of plastic bricks in construction. At the end, the groups disperse and students vote individually via an anonymous online poll whether they are personally in favour or against the use of plastic bricks in construction.

- Create a HAZOP risk assessment for the manufacturing processes of the factory where plastic waste is converted into plastic bricks.

- Develop an educational leaflet for preventing the key injuries and hazards in the process of converting plastic waste into bricks, both for the informal waste pickers and the factory workers.

Acknowledgement: The authors want to acknowledge the work of Engineers Without Borders Netherlands and its partners to tackle the problem of plastic waste. The case is based on the Challenge Based Learning exploratory course Decision Under Risk and Uncertainty designed by Diana Adela Martin at TU Eindhoven, where students got to work on a real-life project about the conversion of plastic waste into bricks to build a washroom facility in a school in Ghana, based on the activity of Engineers Without Borders Netherlands. The project was spearheaded by Suleman Audu and Jeremy Mantingh.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.