Author: Mike Murray BSc (Hons) MSc PhD AMICE SFHEA (Senior Teaching Fellow in Construction Management, Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Strathclyde).

Topic: Links between education for sustainable development (ESD) and intercultural competence.

Tool type: Teaching.

Engineering disciplines: Civil; Any.

Keywords: AHEP; Sustainability; Student support; Local community; Higher education; Assessment; Pedagogy; Education for sustainable development; Internationalisation; Global reach; Global responsibility; EDI.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

Related SDGs: SDG 4 (Quality education); SDG 16 (Peace, justice, and strong institutions).

Educational level: Beginner.

Learning and teaching notes:

This resource describes a coursework aligned to three key pedagogical approaches of ESD. (1) It positions the students as autonomous learners (learner-centred); (2) who are engaged in action and reflect on their experiences (action-oriented); and (3) empowers and challenges learners to alter their worldviews (transformative learning). Specifically, it requires students to engage in collaborative peer learning (Einfalt, Alford, and Theobald 2022; UNESCO 2021). The coursework is an innovative Assessment for Learning” (AfL) (Sambell, McDowell, and Montgomery, 2013) internationalisation at home (Universities UK, 2021) group and individual assessment for first-year civil & environmental engineers enrolled on two programmes (BEng (Hons) / MEng Civil Engineering & BEng (Hons) / MEng Civil & Environmental Engineering). However, the coursework could easily be adapted to any other engineering discipline by shifting the theme of the example subjects. With a modification on the subjects, there is potential to consider engineering components / artifacts / structures, such as naval vessels / aeroplanes / cars, and a wide number of products and components that have particular significance to a country (i.e., Swiss Army Knife).

Learners have the opportunity to:

- Engage in collaborative peer learning and socialise with students from different countries.

- Gain knowledge related to the design and construction of civil engineering buildings and structures.

- Develop a ‘global engineering mindset.’

Teachers have the opportunity to:

- Promote, recognise, and reward intercultural engagement and the development of intercultural competence (IC).

- Raise student awareness of an engineer’s role in the UNSDGs.

Learning and teaching resources:

- Bridges to Prosperity. (2023). Our mission, vision, and belief.

- Carnegie Mellon University. (2023). Sample Group Project Tools

- Cassina, J and Matthews, J.H. (2021). Nature-based solutions, water security and climate change: Issues and opportunities, In Jan Cassin, John H. Matthews and Elena Lopez Gunn (Edits) Nature-Based Solutions and Water Security: An Action Agenda for the 21st Century, Amsterdam: Elsevier pp 3-18

- Hayes, S., Desha, C and Baumeiste, D. (2020). Learning from nature – Biomimicry innovation to support infrastructure sustainability and resilience, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120287

- RedR UK. (2023). The Humanitarian Context in the Middle East.

- Water Aid. (2023). Our Climate Fight.

Rationale:

There have been several calls to educate the global engineer through imbedding people and planet issues in the engineering curriculum (Bourn and Neal, 2008; Grandin and Hirleman 2009). Students should be accepting of this practice given that prospective freshers are ‘positively attracted by the possibility of learning alongside people from the rest of the world’ (Higher Education Policy Unit, 2015:4). Correspondingly, ‘international students often report that an important reason in their decision to study abroad is a desire to learn about the host country and to meet people from other cultures’ (Scudamore, 2013:14). Michel (2010:358) defines this ‘cultural mobility’ as ‘sharing views (or life) with people from other cultures, for better understanding that the world is not based on a unique, linear thought’.

Coursework brief summary extracted from the complete brief:

Civil Engineering is an expansive industry with projects across many subdisciplines (i.e. Bridges, Buildings, Coastal & Marine, Environmental, Geotechnical, Highways, Power including Renewables. In a group students are required to consult with an international mentor and investigate civil engineering (buildings & structures) in the mentor’s home country. Each student should select a different example. These can be historical projects, current projects or projects planned for the future, particularly those projects that are addressing the climate emergency. Students will then complete two tasks:

- Task 1: Group International Poster (10% weighting)

- Task 2: Individual reflective Report (10% weighting)

Time frame and structure:

1. Opening lecture covering:

a. Reasoning for coursework with reference to transnational engineering employers and examples of international engineering projects and work across national boundaries.

b. Links between engineering, people, and planet through the example of biomimicry in civil engineering design (Hayes, Desha, & Baumeister, 2020) or nature-based solutions in the context of civil engineering technology (Cassina and Matthews ,2021).

c. Existence of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as RedR UK (2023) Water Aid (2023) and Bridges to Prosperity (2023).

d. The use of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to address problematic issues such as human rights abuses (Human Rights Watch, 2006) and bribery and corruption (Stansbury and Stansbury) in global engineering projects.

2. Assign students to groups:

a. Identify international mentors. After checking the module registration list, identify international students and invite them to become a mentor to their peers. Seek not to be coercive and explain that it is a voluntary role and to say no will have no impact on their studies. In our experience, less than a handful have turned down this opportunity. The peer international students are then used as foundation members to build each group of four first-year students. Additional international student mentors can be sourced from outside the module to assist each group.

b. Establish team contracts and group work processes using the Carnegie Mellon Group Working Evaluation document

3. Allow for group work time throughout the module to complete the tasks (full description can be found in the complete brief).

Assessment criteria:

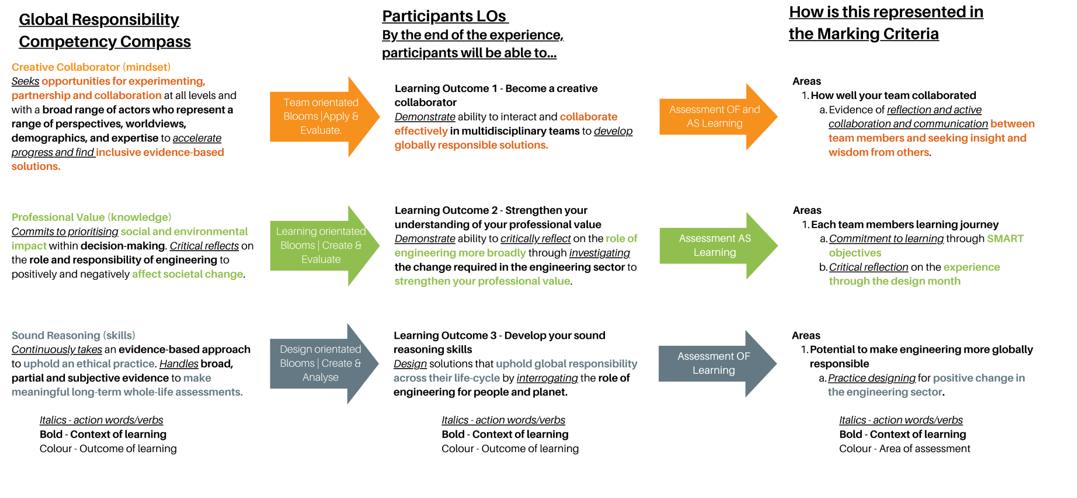

The coursework constitutes a 20% weighting of a 10-Credit elective module- Engineering & Society. The submission has two assessed components: Task 1) a group international poster with annotated sketches of buildings & structures (10% weighting); and Task 2) A short individual reflective writing report (10% weighting) that seeks to ascertain the students experience of engaging in a collaborative peer activity (process), and their views on their poster (product). Vogel et al, (2023, 45) note that the use of posters is ‘well-suited to demonstrating a range of sustainability learning outcomes’. Whilst introducing reflective writing in a first-year engineering course has its challenges, it is recognised that reflective practice is an appropriate task for ESD- ‘The teaching approaches most associated with developing transformative sustainability values stimulate critical reflection and self-reflection’ (Vogel et al, 2023, 6).

Each task has its own assessment criteria and process. Assessment details can be found in the complete coursework brief.

Teaching reflection:

The coursework has been undertaken by nine cohorts of first-year undergraduate civil engineers (N=738) over seven academic sessions between 2015-2024. To date this has involved (N=147) mentors, representing sixty nationalities. Between 2015-2024 the international mentors have been first-year peers (N=67); senior year undergraduate & post-graduate students undertaking studies in the department (N=58) and visiting ERASMUS & International students (N =22) enrolled on programmes within the department.

Whilst the aim for the original coursework aligns with ESD (‘ESD is also an education in values, aiming to transform students’ worldviews, and build their capacity to alter wider society’ -Vogel et al ,2023:21) the reflective reports indicate that the students’ IC gain was at a perfunctory level. Whilst there were references to ‘a sense of belonging, ‘pride in representing my country’, ‘developing friendships’, ‘international mentors’ enthusiasm’ this narrative indicates a more generic learning gain that is known to help students acquire dispositions to stay and to succeed at university (Harding and Thompson, 2011). The coursework brief fell short of addressing the call ‘to transform engineering education curricula and learning approaches to meet the challenges of the SDGs’ (UNESCO,2021:125). Indeed, as a provocateur pedagogy, ‘ESD recognises that education in its current form is unsustainable and requires radical change’ (Vogel et al ,2023, 4).

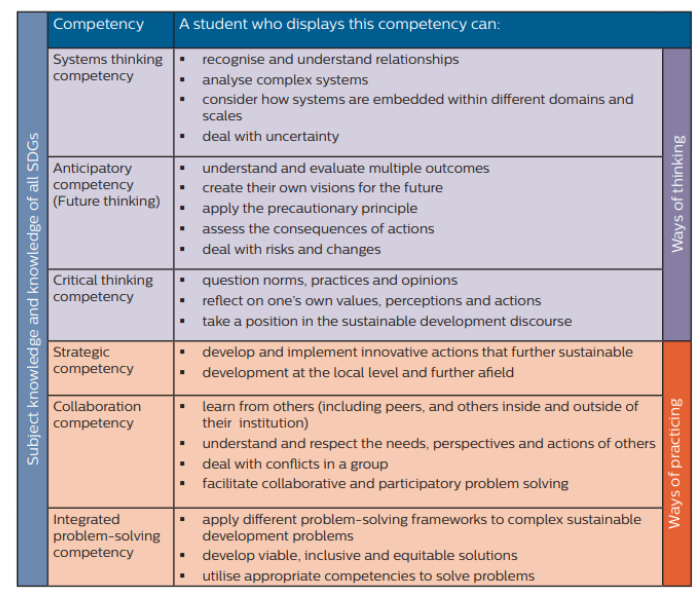

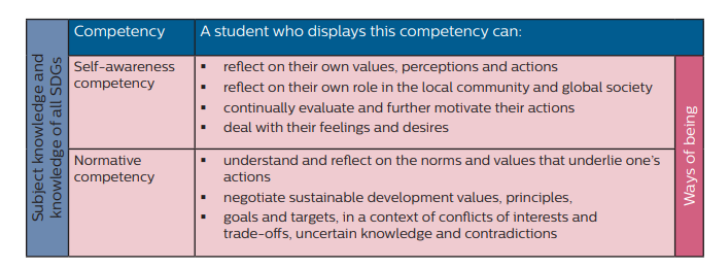

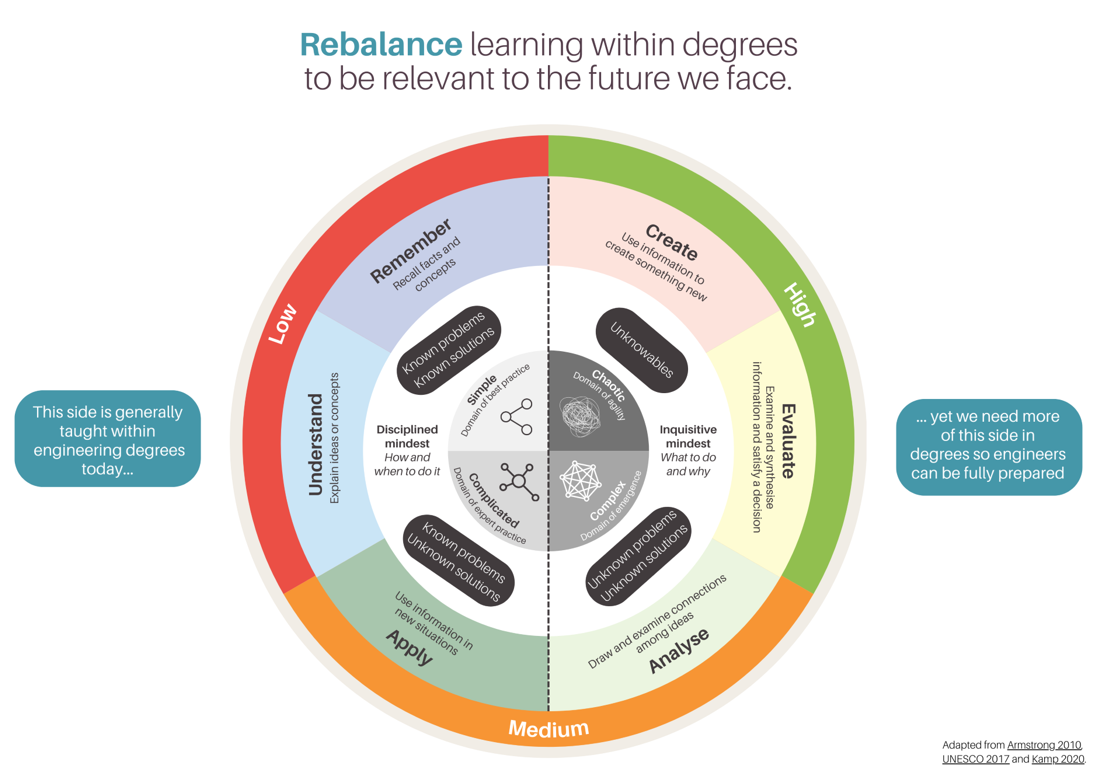

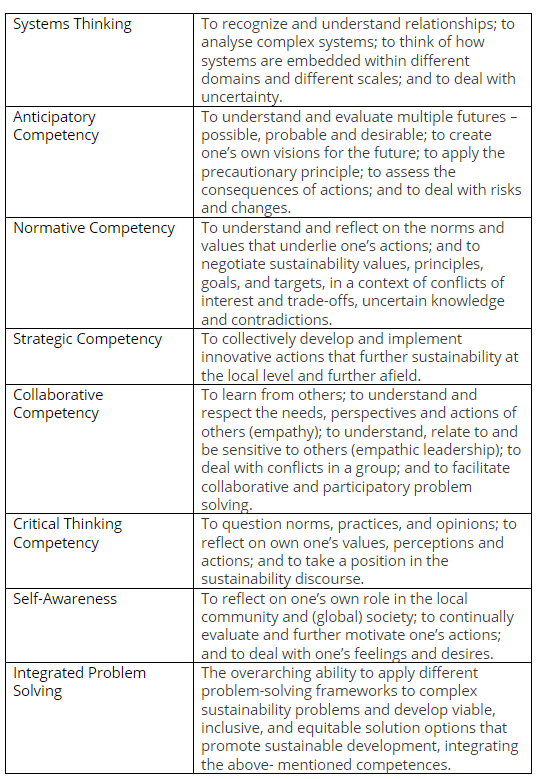

Given the above it is clear that the coursework requirement for peer collaboration and reflective practice aligns to three of the eight key competencies (collaboration, self-awareness, critical thinking) for sustainability (UNESCO, 2017:10). Scudamore (2013:26) notes the importance of these competencies when she refers to engaging home and international students in dialogue- ‘the inevitable misunderstandings, which demand patience and tolerance to overcome, form an essential part of the learning process for all involved’. Moreover, Beagon et al (2023) have acknowledged the importance of interpersonal competencies to prepare engineering graduates for the challenges of the SDG’s. Thus, the revised coursework brief prompts students to journey ‘through the mirror’ and to reflect on how gaining IC can assist their knowledge of, and actions towards the SDG’s.

References:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.