Theme: Collaborating with industry for teaching and learning

Theme: Collaborating with industry for teaching and learning

Authors: Dr Gareth Thomson (Aston University, Birmingham), Dr Jakub Sacharkzuk (Aston University, Birmingham) and Paul Gretton (Aston University, Birmingham)

Keywords: Industry, Engineering Education, Authenticity, Collaboration, Knowledge exchange, Graduate employability and recruitment.

Abstract: This paper describes the work done within the Mechanical, Biomedical and Design Engineering group at Aston University to develop an Industry Club with the aim to enhance and strategically organise industry involvement in the taught programmes within the department. A subscription based model has been developed to allow the hiring of a part-time associate to manage the relationship with industry, academic and student partners and explore ways to develop provision. This paper describes the approach and some of the activities and outcomes achieved by the initiative.

Introduction

Industry is a key stakeholder in the education of engineers and the involvement of commercial engineering in taught programmes is seen as important within degrees but may not always be particularly optimised or strategically implemented.

Nonetheless, awareness of industry trends and professional practice is seen as vital to add currency and authenticity to the learning experience [1,2]. This industry involvement can take various forms including direct involvement with students in the classroom or in a more advisory role such as industrial advisory or steering boards [3] designed to support the teaching team in their development of the curriculum.

Direct input into the curriculum from industry normally involves engagement in dissertations, final year ‘capstone’ project exercises [4], visits [5], guest lectures [6,7], internships [8,9] or design projects [10,11]. These are very commonly linked to design type modules [12,13] or projects where the applied nature of the subject makes industrial engagement easier and are more commonly centred toward later years when students are perceived to have accrued the underpinning skills and intellectual maturity needed to cope with the challenges posed.

These approaches can however be ad hoc and piecemeal. Industry contacts used to directly support teaching are often tied into specific personal relationships through previous research or consultancy or through roles such as the staff involved also being careers or placement tutors. This means that there is often a lack of strategic thinking or sharing of contacts to give a joined up approach – an academic with research in fluid dynamics may not have an easy way to access industrial support or guidance if allocated a manufacturing based module to teach.

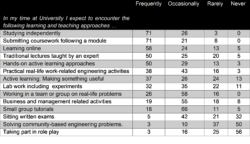

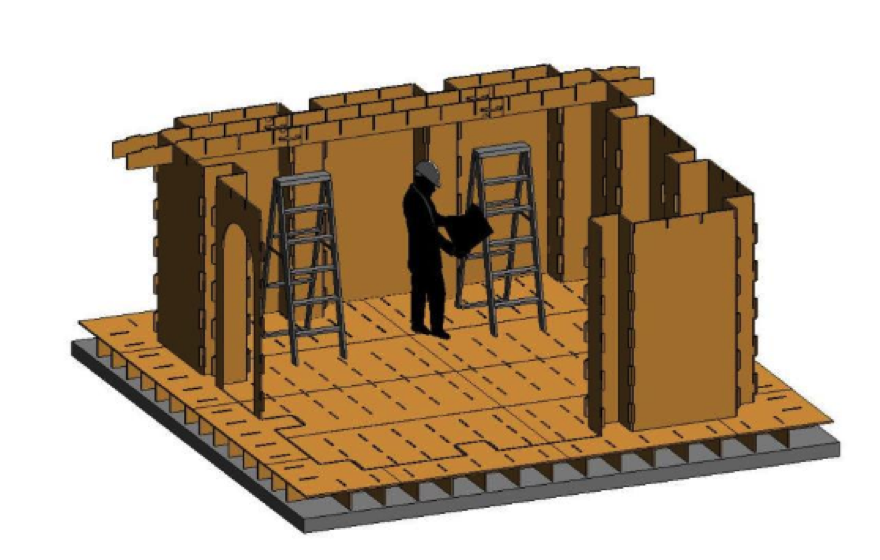

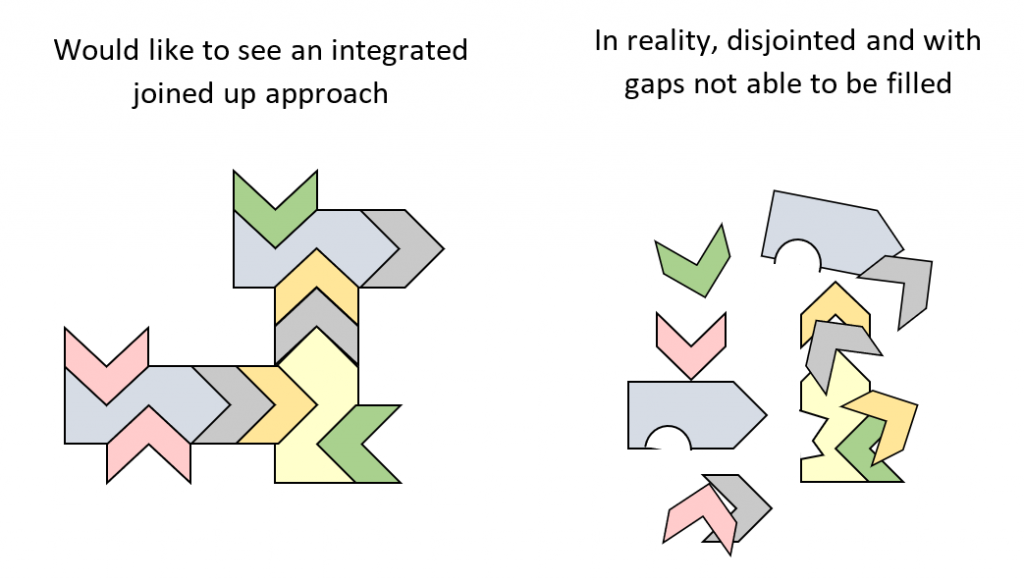

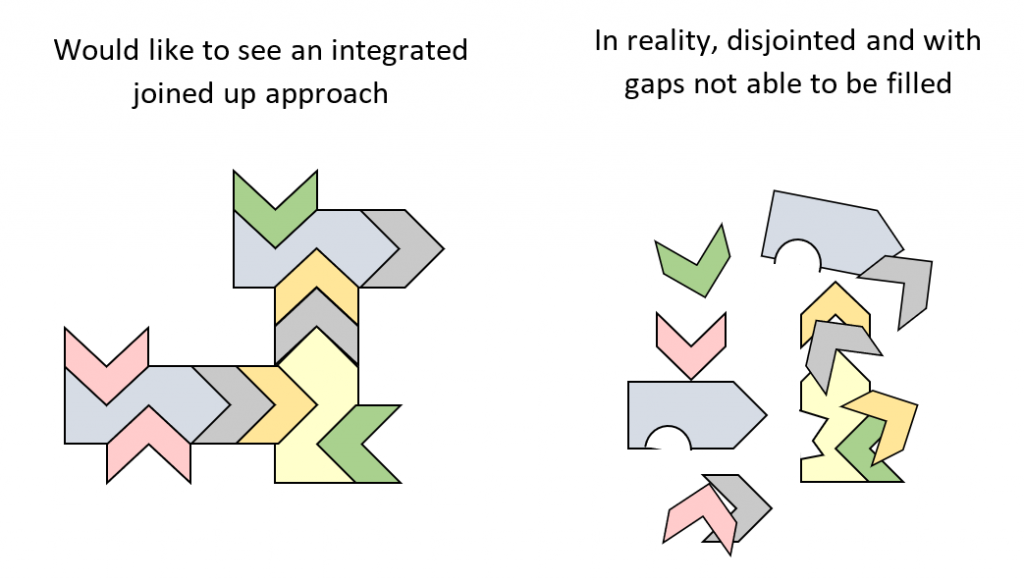

This lack of integration often gives rise to fractured and unconnected industrial involvement (Figure 1) with lack of overall visibility of the extent of industrial involvement in a group and lack of clarity on where gaps exist or opportunities present themselves.

Figure 1 : Industry involvement in degrees is often not as joined up as might be hoped.

As part of professional body accreditation it is also generally expected that Industrial Advisory Boards are set-up and meet regularly to help steer curriculum planning. Day to day pressures however often mean that these do not necessarily operate as effectively as they could and changes or suggestions proposed by these can be slow to implement.

Industry Club

To try to consolidate and develop engagement with industry a number of institutions have developed Industry Clubs [14,15] as a way of structuring and strategically developing industrial engagement in industry.

For companies, such a scheme offers a low risk, low cost involvement with the University, access to students to undertake projects and can also help to raise awareness in the students minds of companies and sectors which may not have the profile of the wider jobs market beyond the big players in the automotive, aerospace or energy sectors. At Aston University industry clubs have been running for several years in Mechanical Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Computer Science.

The focus in this report is the setting up and development of the industry club in the Mechanical, Biomedical and Design Engineering (MBDE) department.

Recruitment of companies was via consolidation of existing contacts from within the MBDE department and engagement with the wider range of potential partners through the University’s ‘Research and Knowledge Exchange’ unit.

The industry focus within the club has been on securing SME partners. This is a sector which has been found to be very responsive. Feedback from these partners has indicated that often getting access to University is seen as ‘not for them’ but when an easy route in is offered, it becomes a viable proposition. By definition SMEs do not have the visibility of multi-nationals and so they can struggle to attract good graduates so the ability to raise brand awareness is seen as positive. From the perspective of academics, the very flat and localised management structure also makes for a responsive partner able to make decisions relatively quickly. Longer term this opens up options to explore more expansive relationships such as KTPs or other research projects and also sets up a network of different but compatible companies able to share knowledge among themselves.

Within MBDE the industry club initially focussed on placing industrially linked projects for final year dissertation students. This was considered relatively ‘low hanging fruit’ with a simple proposition for companies, academics and students.

- The companies get the opportunity to access the physical and student resource of the university

- The students get a more contextualised and live project offering added practical and commercial concerns of a commercial project thereby enhancing their experience and employability

- The academics are able to enhance the curriculum and build industrial contacts who can support both teaching and research going forward.

While this proposal is straightforward it is not entirely without difficulty with matching of academics to projects, expectation management and practical logistics of diary mapping between partners all needing attention.

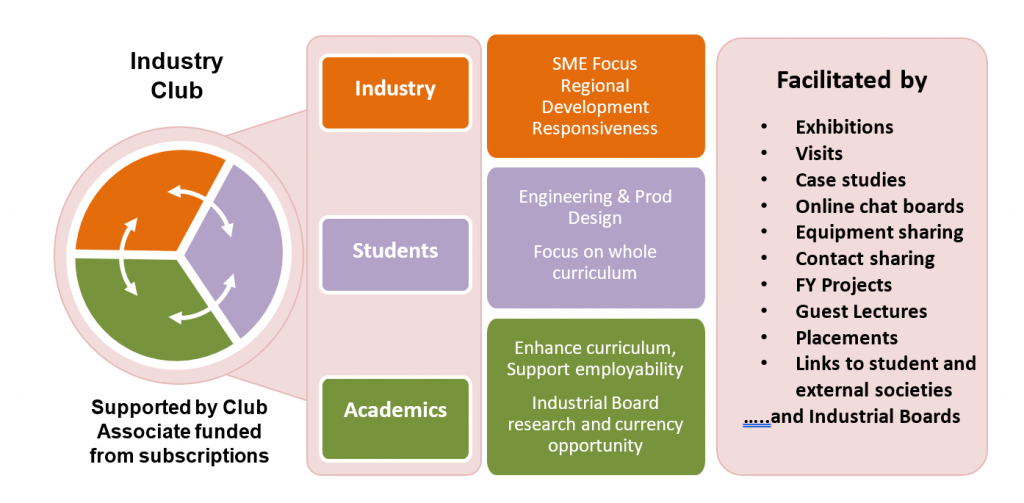

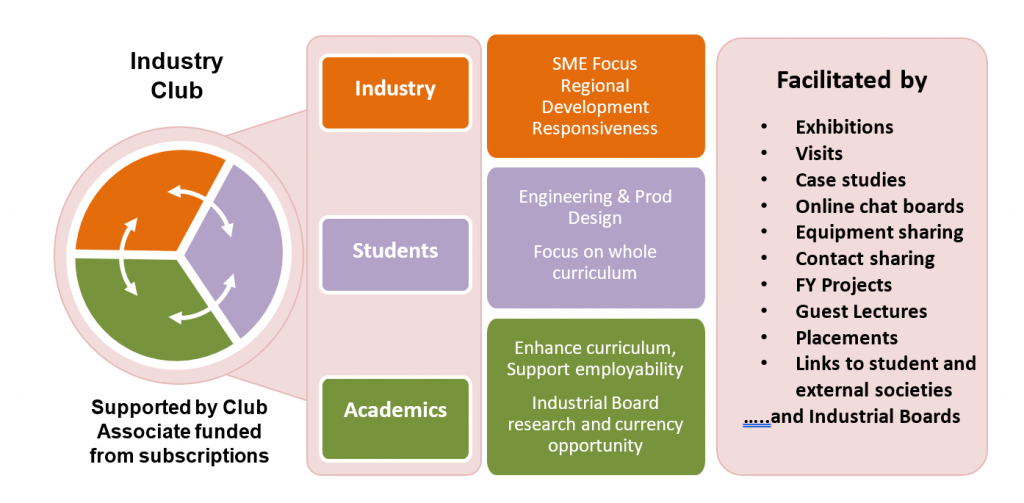

To support this, an Industry Club Associate was recruited to help manage the initiative, funding for this being drawn from industry partner subscriptions and underwritten by the department.

This has allowed the Industry Club to move beyond its initial basis of final year projects to have a much wider remit to oversee much of the involvement of industry in both the teaching programmes directly and in their advising and steering of the curriculum.

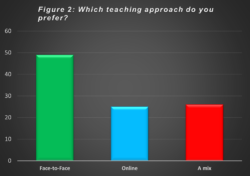

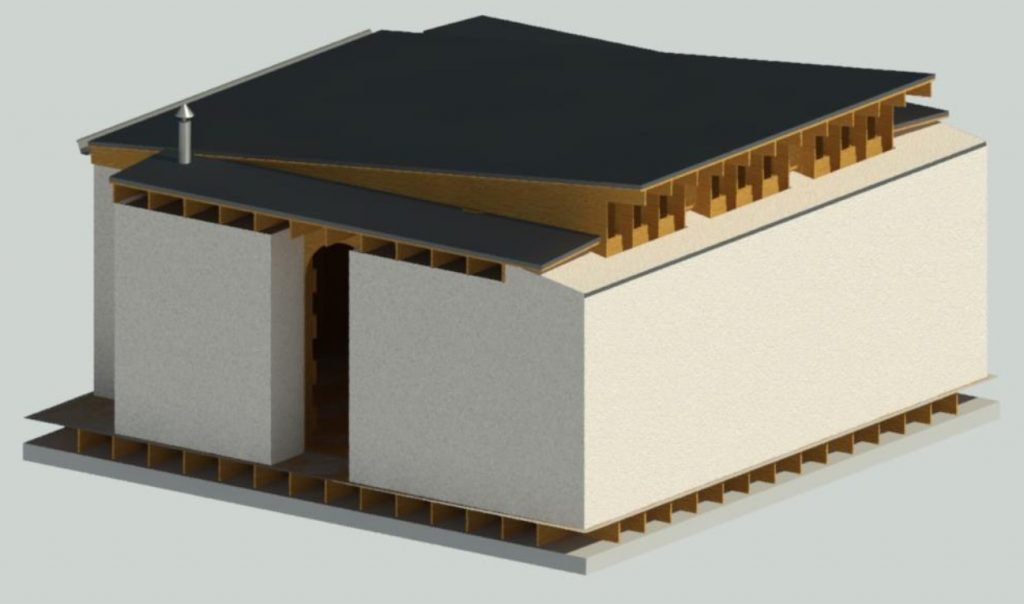

Figure 2 shows schematically the role and activities of the industry club within the group.

Impact Beyond Projects

The use of the Industry Club to co-ordinate and bolster other industry activity within the department has gone beyond final year projects. These can be seen in Figure 2.

The Industrial Advisory Board has now become linked to the Industry Club and so with partners now involved in the wider activities of the club involvement is now not exclusively limited to twice yearly meeting but is an active ongoing partnership using the projects, other learning and teaching activity and a LinkedIn group to create a more dynamic and responsive consultation body. A subset of the IAB is now also made up entirely of recent alumni to act as a bridge between the students and practising industry to help spot immediate gaps and opportunities to support students in this important transition.

Figure 2 : Industry Club set-up and Activity

The club has also developed a range of other industrially linked activities in support of teaching and learning.

While industrial involvement is relatively easy to embed in project or design type modules this is not so easy in traditional underpinning engineering science type activity.

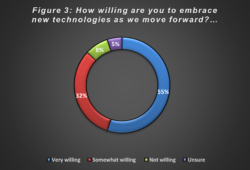

To address the lack of industrial content in traditional engineering science modules a pilot interactive online case studies be developed to help show how fundamental engineering science can be applied in authentic industrial problems. A small team consisting of an academic, the industry club associate and an industrialist was assembled.

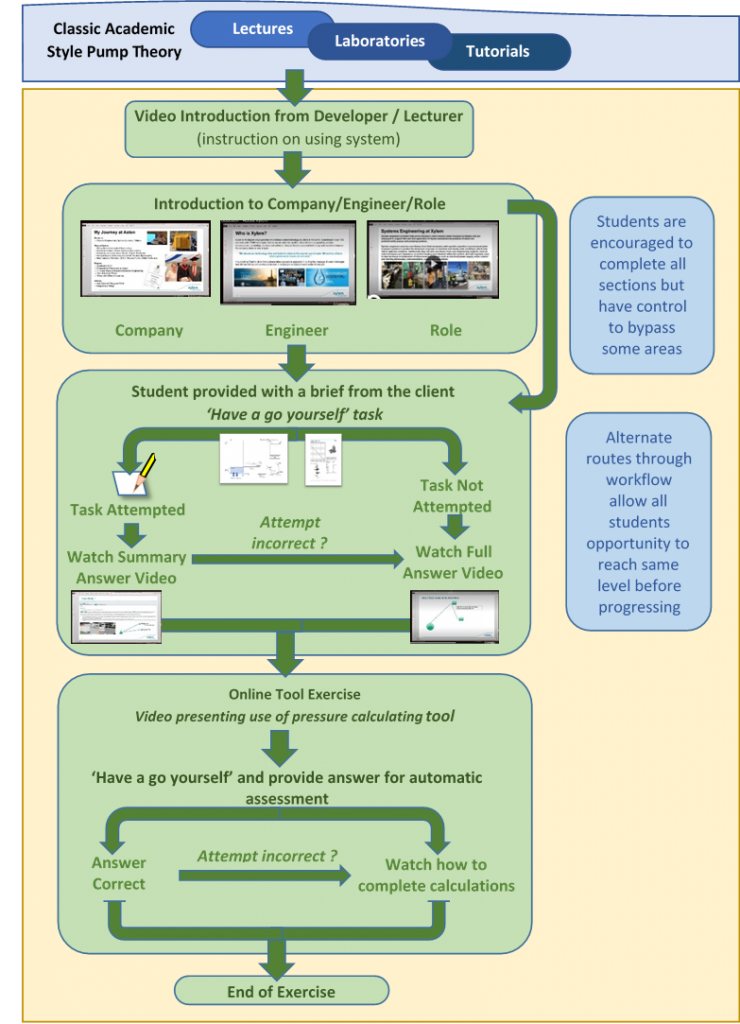

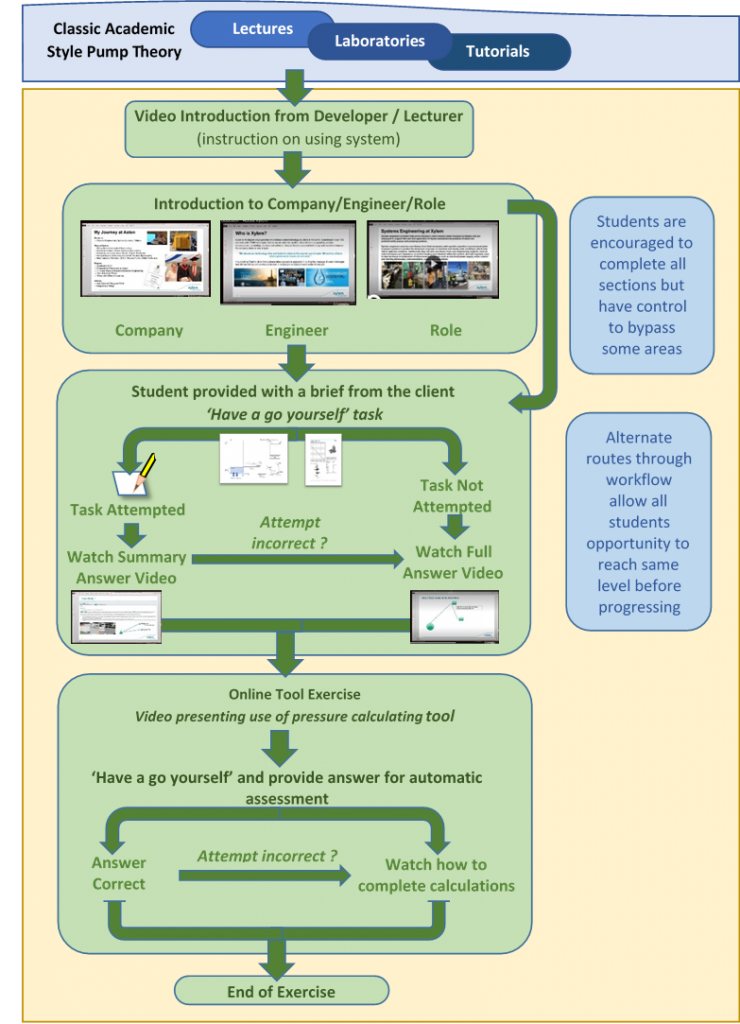

This team developed an online pump selection tool which combined interactive masterclasses and activities, introduced and explained by the industrialist to show how the classic classroom theory could be used and adapted in real world scenarios (Figure 3). This has been well-received by students, added authenticity to the curriculum and raised awareness in student minds of the perhaps unfashionable but important and rewarding water services sector.

Figure 3 : Online Interactive Activity developed as part of industry club activity

Further interactions developed by the Industry Club, and part of its remit to embed industrial links at all stages of the degree, include the involvement of an Industrial Partner on a major wind turbine design, build and test project engaged in as group exercises by all students in year one. Here the industrialist, a wind energy professional, contextualises work while his role is augmented by a recent alumni member of the Industrial board who is currently working as a graduate engineer on offshore wind and who completed the same module as the students four years or so previously.

Conclusion

While the development of the Industry Club and its associated activity can not be considered a panacea, it has significantly developed the level of industry involvement within programmes. More crucially it moves away from an opaque and piecemeal approach to industry engagement and offers a more transparent framework and structure on which to hang industry involvement to support academics and industry in developing and maximising the competencies of graduates.

References

- Pantzos, P.,Gumaelius L.,Buckley J. and Pears A., “On the role of industry contact on the motivation and professional development of engineering students,” 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 2019, pp. 1-8, doi: 10.1109/FIE43999.2019.9028621.

- Male, S.A., King, R. (2019). Enhancing learning outcomes from industry engagement in Australian engineering education. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 101–117.

- Genheimer SR, Shehab R. The effective industry advisory board in engineering education – a model and case study. 2007 37th Annual Frontiers In Education Conference – Global Engineering: Knowledge Without Borders, Opportunities Without Passports, 2007 FIE ’07 37th Annual. October 2007. doi:10.1109/FIE.2007.4418027

- Surgenor B, Mechefske C, Wyss U, Pelow J,(2005) Capstone Design – Experience with Industry Based Projects, 1st Annual CDIO Conference Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada June 7 to 8, 2005

- Carbone A, Rayner GM, Ye J, Durandet Y (2020) Connecting curricula content with career context: the value of engineering industry site visits to students, academics and industry, European Journal of Engineering Education, 45:6, 971-984, DOI: 10.1080/03043797.2020.1806787

- Fang N, Mcneill L, Spall R, Barr P (2019) Impacts of Industry Seminars and a Student Design Competition in an Engineering Education Scholarship Program International Journal of Engineering Education Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 674–684, 2019

- Ringwood JV(2013) Integrating industrial seminars within a graduate engineering programme, European Journal of Engineering Education, 38:2, 141-148, DOI: 10.1080/03043797.2012.755497

- Magnell M, Geschwind L, Kolmos A (2017) Faculty perspectives on the inclusion of work-related learning in engineering curricula, European Journal of Engineering Education, 42:6, 1038-1047, DOI: 10.1080/03043797.2016.1250067

- Tennant S, Murray M, Gilmour B, Brown L. Industrial Work Placement in Higher Education: A Study of Civil Engineering Student Engagement. Industry and Higher Education. 2018;32(2):108-118. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- Mejtoft T, (2015) Industry Based Projects And Cases: A CDIO Approach To Students’ Learning, Proc. of the 11th International CDIO Conference, Chengdu University of Information Technology, Chengdu, Sichuan, P.R. China, June 8-11, 2015.

- Lima RM, Dinis-Carvalhoa J, Sousaa RM, Arezesa P, Mesquita D, (2017), Production, Development of competences while solving real industrial interdisciplinary problems: a successful cooperation with industry, 27(spe), e20162300, 2017 | DOI: 10.1590/0103-6513.230016

- Seidel R, Shahbazpour M, Walker D, Shekar A, Chambers C, (2011), An Innovative Approach To Develop Students’ Industrial Problem Solving SkillsProc. of the 7th International CDIO Conference, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen, June 20 – 23, 2011

- Thomson G, Prince M, McLening C, Evans C, (2012) A Comparison Between Different Approaches To Industrially Supported Projects, Proc. of the 8th International CDIO Conference, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, July 1 – 4, 2012

- University of Canterbury, (2021), Collaborate – College of Engineering

- Aston University (2021), Computer Science Industry Club Brochure

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.