Authors: Professor Emanuela Tilley, (UCL); Associate Professor Kate Roach (UCL); Associate Professor Fiona Truscott (UCL).

Topic: Sustainability must-haves in engineering project briefs.

Type: Guidance.

Relevant disciplines: Any.

Keywords: PBL; Assessment; Project brief; Learning outcomes; Pedagogy; Communication; Future generations; Decision-making; Design; Ethics; Sustainability; AHEP; Higher education.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

Related SDGs: All.

Supporting resources:

- EWB-UK Global Responsibility Compass

- Evidencing sustainability competencies in assessment

- EPC’s Engineering Ethics Toolkit

- Sustainability Resources Library: Knowledge tools

Premise:

Projects, and thus project-based learning, offer valuable opportunities for integrating sustainability education into engineering curricula by promoting active, experiential learning through critical and creative thinking within problem-solving endeavours and addressing complex real-world challenges. Engaging in projects can have a lasting impact on students’ understanding and retention of knowledge. By working on projects related to sustainability, students are likely to internalise key concepts and develop a commitment to incorporating sustainable practices into their future engineering endeavours.

Building a brief:

Project briefs are a powerful tool for integrating sustainability into engineering education through project-based learning. They set the tone, define the scope, and provide the parameters for students to consider sustainability in their engineering projects, ensuring that future engineers develop the knowledge, skills, and mindset needed to address the complex challenges of sustainability.

To ensure sustainability has a central and/or clear role within an engineering project, consider the following as you develop the brief:

1. Sustainability as part of goals, objectives, and requirements. By explicitly including sustainability objectives in the project brief, educators communicate the importance of considering environmental, social, and economic factors in the engineering design and implementation process. This sets the stage for students to integrate sustainability principles into their project work.

2. Context: Briefs should always include the context of the project so that students understand the importance of place and people to an engineered solution. Below are aspects of the context to consider and provide:

- What is the central problem for the project?

- Where is the problem/project located? What data will be given to students to describe the context of the problem? Why is the context important and how does it relate to expectations of solving of the problem or the project solution

- Who are the people directly impacted by the scenario and central to the context? What is the problem that they face and why? How are they associated with the project and why do they need to be considered?

- When in time does this scenario/context exist? How does the data or information re. the context support the time of the scenario?

3. Stakeholders: Sustainability is intertwined with the interests and needs of various stakeholders. Project briefs can include considerations for stakeholder engagement, prompting students to identify and address the concerns of different groups affected by the project. This reinforces the importance of community involvement and social responsibility in engineering projects. Below are aspects of the stakeholders to consider and provide:

- Who are the main stakeholders (i.e. users) and why are they important to the context? (see above) What are their needs and what are their power positions

- Who else should be considered stakeholders in the project? How do they influence the project by their needs, interest and power situations?

- Have you considered the earth and its non-human stakeholders, its inhabitants or its landscape?

- Do you want to provide this information to the students or is this part of the work you want them to do within the project?

4. Ethical decision-making: Including ethical considerations related to sustainability in the project brief guides students in making ethical decisions throughout the project lifecycle. The Ethics Toolkit can provide guidance in how to embed ethical considerations such as:

- Explicitly state ethical expectations and frame decisions as having ethical components.

- Prompt and encourage students to think critically about the consequences of their engineering choices on society, the environment, and future generations.

5. Knowns and unknowns: Considering both knowns and unknowns is essential for defining the project scope. Knowing what is already understood and what remains uncertain allows students to set realistic and achievable project goals. Below are aspects of considering the knowns and unknowns aspects of a project brief to consider and provide:

- What key information needs to be provided to the students to address the problem given?

- What is it that you want the students to do for themselves in the early part of the project – i.e. research and investigation and then in the process of their problem solving and prototyping/testing and making?

6. Engineering design process and skills development: The Project Brief should support how the educator wants to guide students through the engineering design cycle, equipping them with the skills, knowledge, and mindset needed for successful problem-solving. Below are aspects of the engineering design process and skills development to consider and provide:

- What process will the students follow in order to come to a final output or problem solution? What result is required of the students (i.e. are they just coming up with concepts or ideas? Do they need to justify and thus technical argue their chosen concept? Do they need to design, build/make and test a prototype or model to show their design and building/making skills as well? Do they need to critically analyse it using criteria based on proof of concept or sustainability goals – ie. It is desirable? Viable? Responsible? Feasible?)

- What skills should students be developing through the project? Some possibilities are (depending on how far they expect students to complete the solution), however the sustainability competencies are relevant here too:

a. Research – investigate,

b. Creative thinking – divergent and convergent thinking in different parts of the process of engineering design,

c. Critical thinking – innovation model analysis or other critical thinking tools,

d. Decision making – steps taken to move the project forward, justifying the decision making via evidence,

e. Communication, collaboration, negotiation, presentation,

f. Anticipatory thinking – responsible innovation model AREA, asking in the concept stages (which ideas could go wrong because of a double use, or perhaps thinking of what could go wrong?),

g. Systems thinking.

7. Solution and impact: Students will need to demonstrate that they have met the brief and can demonstrate that they understand the impact of their chosen solution. Here it would need to be clear what the students need to produce and how long it is expected to take them. Other considerations when designing the project brief to include are:

- Is the brief for a module or a short activity? What is the ideal number of students in a team? Is it disciplinary-based or interdisciplinary (and in this case – which disciplines would be encouraged to be included).

- We would want the students to understand and discuss the trade-offs that they had to consider in their solution.

Important considerations for embedding sustainability into projects:

1. Competences or content?

- Embedding and/or developing competences is a normal part of project work. When seen as a set of competences sustainability is crosscutting in the same way as other HE agendas such as employability, global citizenship, decolonisation and EDI. See the Global Responsibility competency compass for an example of how competencies can be developed for engineering practice.

- Embedding sustainability content often requires additional material, even if it is only in adapting one of the project phases/outcomes to encourage students to think through sustainable practice. For more guidance on how to adapt learning outcomes, see the Engineering for One Planet Framework (aligned to AHEP4).

2. Was any content added or adapted?

- Was any content adapted to include sustainability awareness?

– What form of content, seminars, readings, lectures, tutorials, student activity

- Were learning objectives changed?

- Did you have to remove material to fit in the new or adapted content?

- Were assessments changed?

3. Competencies

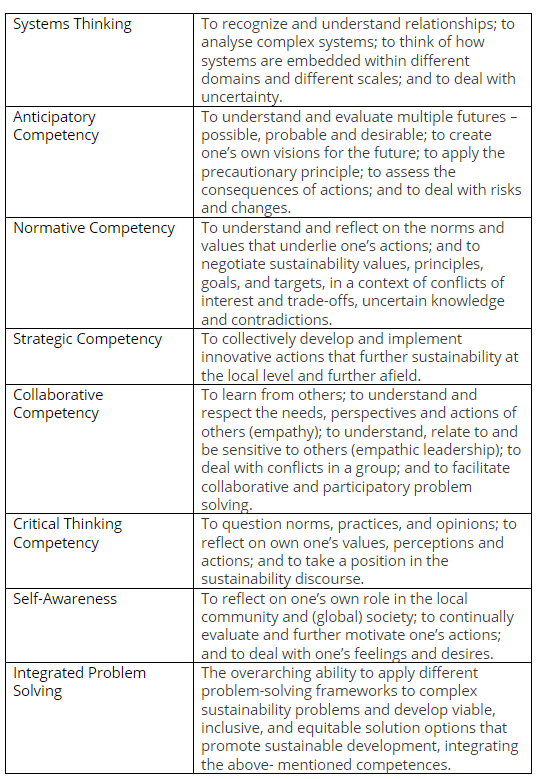

UNESCO has identified eight competencies that encompass the behaviours, attitudes, values and knowledge which facilitate safeguarding the future. These together with the SDGs provide a way of identifying activities and learning that can be embedded in different disciplinary curricula and courses. For more information on assessing competences, see this guidance article.

- Did you map the competences that you already support before changing anything?

- What kind of activities did you add to support the development of the competences you wish to target?

- Did you explain to the students that these were the competences that you were targeting and that they are considered necessary for all who go on to work and live in a warming world?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.