Theme: Collaborating with industry for teaching and learning, Knowledge exchange, Research, Graduate employability and recruitment

Authors: Steve Jones (Siemens), Associate Prof David Hughes (Teesside University), Prof Ion Sucala (University of Exeter), Dr Aris Alexoulis (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Dr Martino Luis (University of Exeter)

Keywords: Digitalisation, Partnership, Collaboration, Network

Abstract: Siemens have worked together with university academics from 10 institutions to develop and implement holistic digitalisation training and resources titled the “Connected Curriculum”. The collaboration has proved hugely successful for teaching, research and knowledge transfer. This model and collaboration is an excellent example of industry informed curriculum development and the translational benefits this can bring for all partners.

Collaboration between academic institutions and industry is a core tenet of all Engineering degrees; however its practical realisation is often complex. Academic institutions employ a range of strategies to improve and embed their relationships with industry. These approaches are often institution specific and do not translate well across disciplines. This leaves industries with multiple academic partnerships, all operating differently and a constant task of managing expectations on both sides. The difference about Siemens Connected Curriculum is that it is an industry-led engagement which directly seeks to address and resource these challenges.

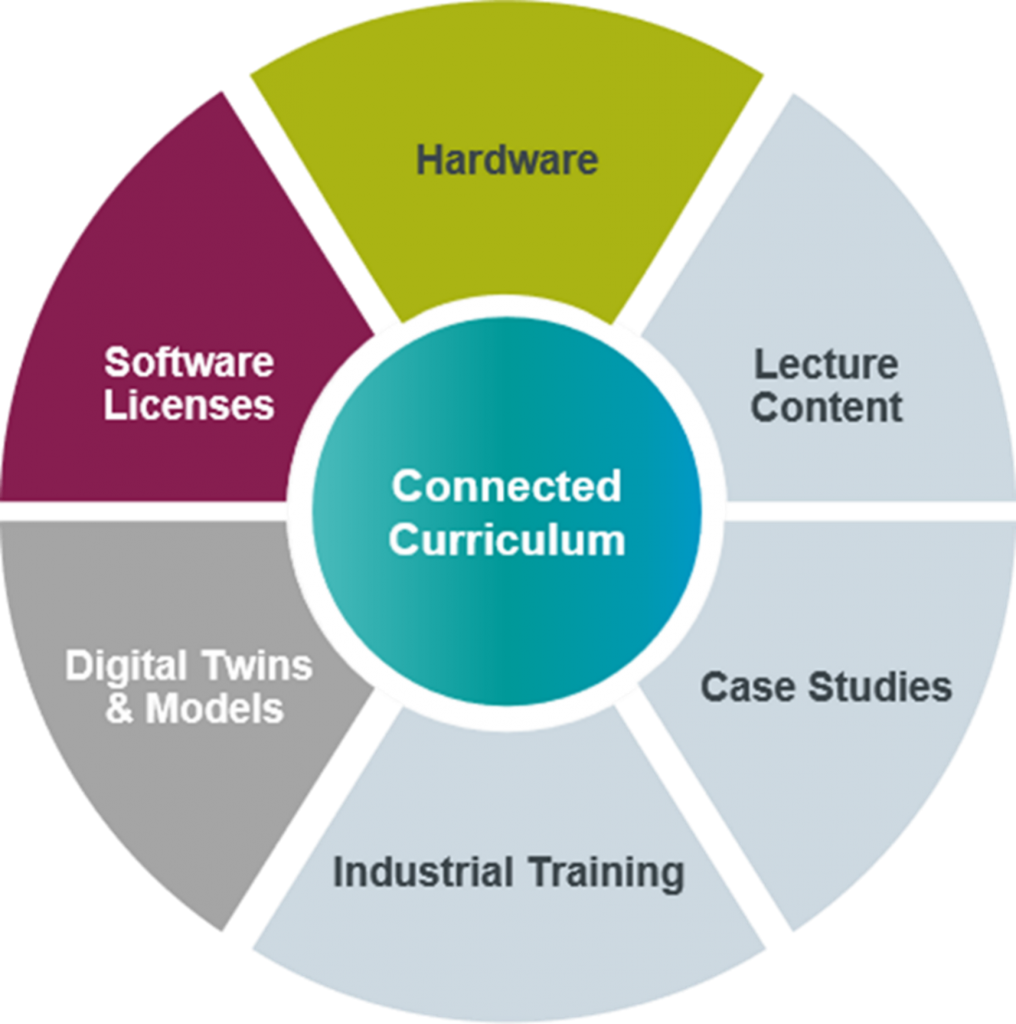

In 2019 Siemens developed the “Connected Curriculum”, a suite of resources (see fig1) to support and enable academic delivery around the topic of ‘Industry 4’. A novel multi-partner network was formed between Siemens, Festo Didactic and universities to develop and deliver the curriculum using real industrial hardware and software. Siemens is uniquely positioned to support on Industry 4 because it is one of the few companies that has a product portfolio that spans the relevant industrial hardware and software. As a result, Siemens is more able to bring together the cyber-physical solutions that sit at the heart of Industry 4.

Figure 1 – Core resources of Siemens Connected Curriculum

Connected Curriculum Aims

The scheme set out with a number of designed aims for the benefit of both Siemens and the partner universities.

- Increase the ability of graduates to have an impact on complex Industry 4 topics

- Develop graduate employability/recruitment through real world understanding nurtured through industrial case studies and problem-based engagement with industry.

- Expanding the market with engineers familiar with Siemens’ industrial hardware and software

- Develop and keep current the skills of academics in a rapidly changing technical landscape

- A model that supported sustained industrial investment in academic capability

- A model that was scalable to engage future institutions

Connected Curriculum Implementation

In 2019, four universities agreed with Siemens to create a pilot programme with a common vision for where Siemens could add value, how the university partners could collaborate, and how the network could scale. The initial pilot programme included Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), The University of Sheffield (UoS), Middlesex University (Mdx), and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). Since the success of its pilot programme, as of Jan 2022 Connected Curriculum now has ten UK university partners with the addition of Teesside University, Coventry University, Exeter University, Salford University, Sheffield Hallam University and The University West of England. The consortium continues to grow and is now expanding internationally. The university academics and the Connected Curriculum team at Siemens have worked together to develop holistic digitalisation training and resources.

Siemens developed a specific team to resource Connected Curriculum, which now includes a full-time Connected Curriculum lead and two Engineering support staff. In addition to the direct team, the initiative also relies on input from a range of experts across the multiple Siemens business units.

The collaboration between multiple institutions and Siemens has proved hugely successful for teaching, research and knowledge transfer. We feel this model and collaboration is an excellent example of industry informed curriculum development and the translational benefits this can bring for all partners. Evidential outcomes of these benefits are demonstrated through the following examples.

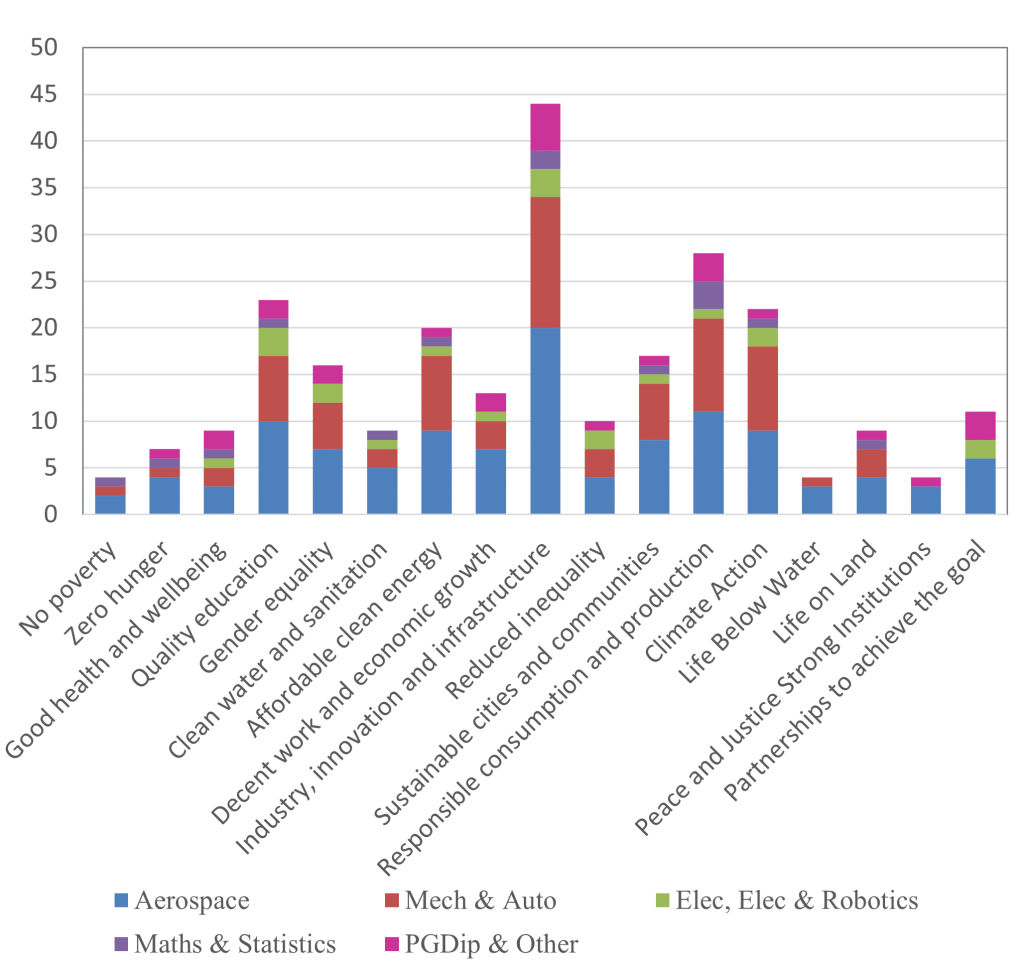

Multi-disciplinary delivery

In 2020 Teesside University’s School of Computing, Engineering and Digital Technologies completed a module review including the embedding of digitalisation, resourced through Connected Curriculum, across its Engineering degrees. A discipline specific, scaffolded approach was developed, enabling students to build on previous learning. This includes starting at a component level and building towards fully integrated cyber-physical systems and plants. Connected Curriculum resources are used to inform and resource new modules including Robotics Design and Control and Process Automation. Due to the inherent need for multi-disciplinary working on digitalisation projects many of these have been structured as shared modules. As Siemens work across such a broad range of industries we are able to embed case studies and tasks which are relevant and foster collaborative working. The need for these digital skills and collaborative approaches has been highlighted by a number of studies including the joint 2021 IMechE/IET survey report: The future manufacturing engineer – ready to embrace major change?

Impact on Industry

In May 2021, Exeter’s Engineering Management group and a manufacturer of electric motors, generators, power electronics, and control systems (located in Devon, UK) collaborated to create digital twins for the assembly line of the Internal Permanent Magnet Motor. With the support from Siemens, we implemented Siemens Tecnomatix Plant Simulation to develop the models. The aim was to optimise assembly line performance of producing the Internal Permanent Magnet Motor such as cycle time, resource utilisation, idle time, throughput and efficiency. What-if scenarios (e.g. machine failure, various material handling modes, absenteeism, bottlenecks, demand uncertainty and re-layout workstations) were performed to build resilient, productive and sustainable assembly lines. Two MSc students were closely involved in this collaborative project to carry out the modelling and the experiments. Our learners have experienced hands-on engineering practice and action-oriented learning to implement Siemens plant simulation in industry.

Industrially resourced project-based learning

In 2020 Siemens was involved in the Ventilator Challenge UK (VCUK) consortium that was formed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. VCUK was tasked with ramping up production of ventilators from 10/week to 1500/week to produce a total of 13500 in just 12 weeks. Inspired by this very successful project, academics at MMU approached the Connected Curriculum team asking if the project could be replicated with a multidisciplinary group of 2nd year Engineering students. MMU Academics and Engineers from Siemens codeveloped a project pack using an open-source ventilator design from Medtronic. The students were tasked with designing a manufacturing process that would produce 10000 ventilators in 12 weeks. The students had 6 weeks to learn how to use the industry standard tools required for plant simulation (Siemens Tecnomatix) and to carry out the project successfully. The project attracted media attention and was featured in articles 1 and 2.

Keys to Success

So, what made the Connected Curriculum so successful? Digitalisation is clearly a current trend and so timing has played an important role. One of the most significant reasons is that Siemens not only led the scheme but resourced it. This has been key to supporting the rapidly growing need for relevant academic expertise. The on-going support from Siemens is also key for issue resolution and to support implementation for universities in adopting new curriculum. Engaging academic partners early in the process was key to ensuring the content was relevant and appropriately pitched.

Siemens breadth and depth of technological expertise across numerous technologies has been a key factor in the success of this initiative. Combined with its global engineering community, this has facilitated a rich integrated curriculum approach which covers a range of aligned technologies. Drawing on internal experts across its global community has allowed the initiative to benefit from a wealth of existing knowledge and resources. Having reached critical mass the initiative is now financially self-sustaining. Without reaching this milestone continued engagement would have been impossible.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.