Case enhancement: Developing an internet constellation

Case enhancement: Developing an internet constellation

Activity: Anatomy of an internet satellite.

Author: Sarah Jayne Hitt, Ph.D. SFHEA (NMITE, Edinburgh Napier University).

Overview:

This enhancement is for an activity found in the Dilemma Part two section. It is based on the work done by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler and published by the SHARE Lab of the SHARE Foundation and the AI Now Institute of New York University, which investigates the “anatomy” of an Amazon Echo device in order to “understand and govern the technical infrastructures” of complex devices. Educators should review the Anatomy of an AI website to see the map and the complementary discussion in order to prepare and to get further ideas. This activity is fundamentally focused on developing systems thinking, a competency viewed as essential in sustainability that also has many ethical implications. Systems thinking is also an AHEP outcome (area 6). The activity could also be given a supply chain emphasis.

This could work as either an in-class activity that would likely take an entire hour or more, or it could be a homework assignment or a combination of the two. It could easily be integrated with technical learning. The activity is presented in parts; educators can choose which parts to use or focus on.

1. What are the components needed to make an internet satellite functional?:

First, students can be asked to brainstorm what they think the various components of an internet satellite are without using the internet to help them. This can include electrical, mechanical, and computing parts.

Next, students can be asked to brainstorm what resources are needed for a satellite to be launched into orbit. This could include everything from human resources to rocket fuel to the concrete that paves the launch pad. Each of those resources also has inputs, from chemical processing facilities to electricity generation and so forth.

Next, students can be asked to brainstorm what systems are required to keep the internet satellite operational throughout its time in orbit. This can include systems related to the internet itself, but also things like power and maintenance.

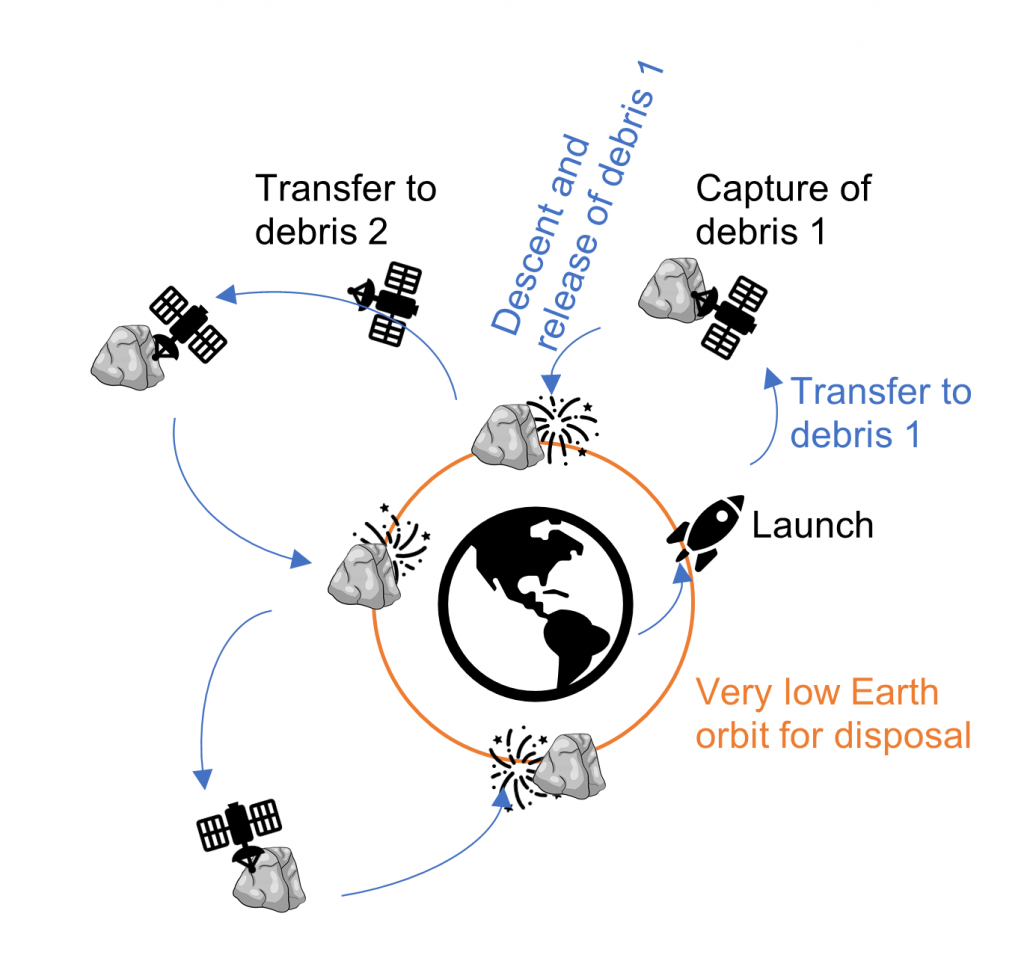

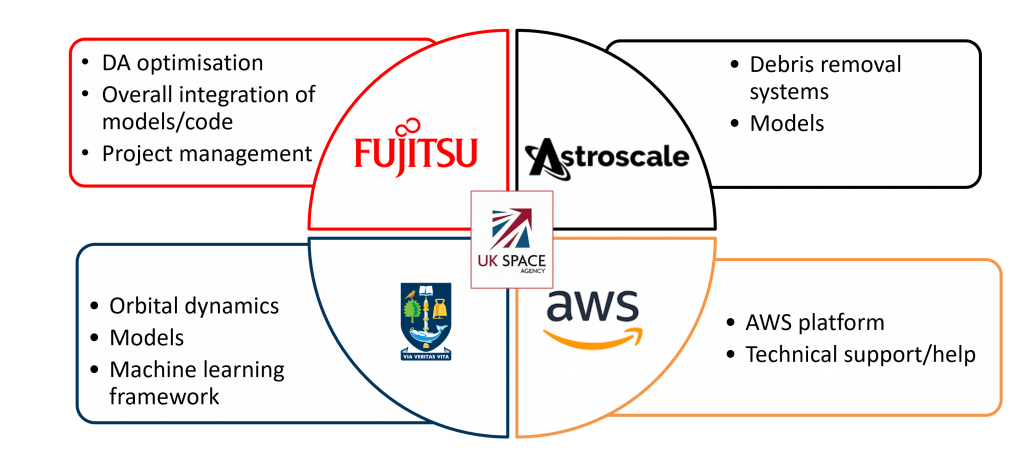

Finally, students can be asked to brainstorm what resources will be needed to manage the satellite’s end of life.

Small groups of students could each be given a whiteboard to make a tether diagram showing how all these components connect, and to try to determine the path dependencies between all of them.

To emphasise ethics explicitly, educators could ask students to imagine where within the tether diagram there could be ethical conflicts or dilemmas and why. Additionally, students could reflect on how changing one part of the system in the satellite would affect other parts of the system.

2. How and where are those components made?:

In this portion of the activity, students can research where all the parts of those components and systems come from – including metals, plastics, glass, etc. They should also research how and where the elements making up those parts are made – mines, factories, chemical plants, etc. – and how they are then shipped to where they are assembled and the corresponding inputs/outputs of that process.

Students could make a physical map of the globe to show where the raw materials come from and where they “travel” on their path to becoming a part of the internet satellite system.

To emphasise ethics explicitly, educators could ask students to imagine where within the resources map there could be ethical conflicts or dilemmas and why, and what the sustainability implications are of materials sourcing.

3. The anatomy of data:

In this portion of the activity, students can research how the internet provides access to and stores data, and the physical infrastructures required to do so. This includes data centres, fibre optic cables, energy, and human labour. Whereas internet service is often quite localised (for instance, students may be able to see 5G masts or the service vans of their internet service provider), in the case of internet satellites it is very distant and therefore often “invisible”.

To emphasise ethics explicitly, educators could ask students to debate the equity and fairness of spreading the supply and delivery of these systems beyond the area in which they are used. In the case of internet satellites specifically, this includes space and the notion of space as a common resource for all. This relates to other questions and activities presented in the case study.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.