Case enhancement: Developing a school chatbot for student support services

Case enhancement: Developing a school chatbot for student support services

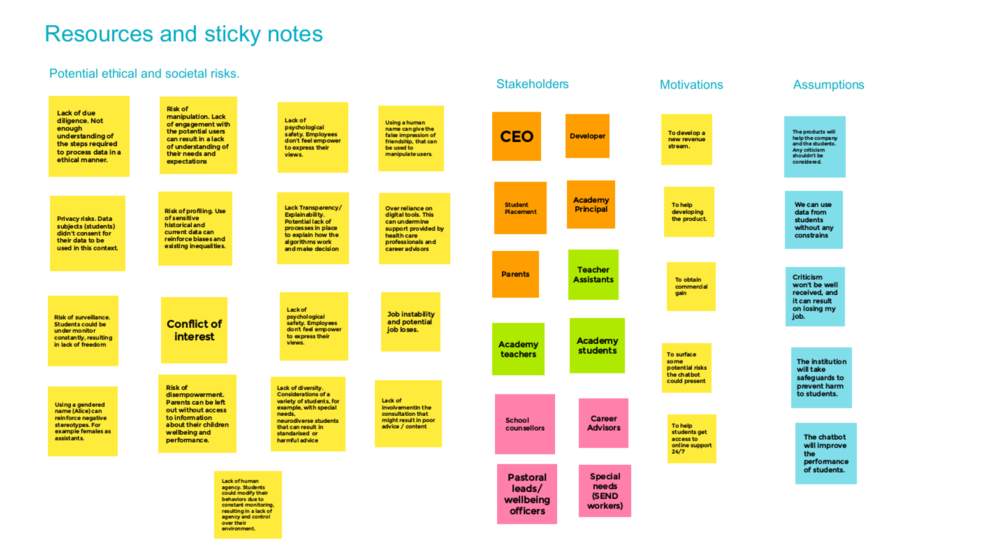

Activity: Stakeholder mapping to elicit value assumptions and motivations.

Author: Karin Rudolph (Collective Intelligence).

Overview:

This enhancement is for an activity found in point 5 of the Summary section of the case study.

What is stakeholder mapping?

- Stakeholder mapping is the visual process of laying out the people, also called stakeholders, who are involved with or affected by an issue and can influence a project, product or idea.

What is a stakeholder?

- Stakeholders are people, groups or individuals who have the power to affect or be affected by a process, project or product.

Mapping out stakeholders will help you to:

- Identify the stakeholders you need to collaborate with to ensure the success of the project.

- Understand the different perspectives and points of view people have and how these experiences can have an impact on your project or product.

- Map out a wide range of people, groups or individuals that can affect and be affected by the project.

Stakeholder mapping:

The stakeholder mapping activity is a group exercise that provides students with the opportunity to discuss ethical and societal issues related to the School Chatbot case study. We recommend doing this activity in small groups of 6-8 students per table.

Resources:

- Stakeholder mapping: a complete guide with examples

- Stakeholder mapping & analysis template

- Stakeholder mapping 101

Materials:

To carry out this activity, you will need the following resources:

1. Sticky notes (or digital notes if online).

2. A big piece of paper or digital board (Jamboard, Miro if online) divided into four categories:

-

- Manage closely.

- Keep satisfied.

- Keep informed.

- Monitor.

3. Markers and pencils.

The activity:

- Begin the activity by asking the students to write a list of stakeholders involved in or affected by the school chatbot.

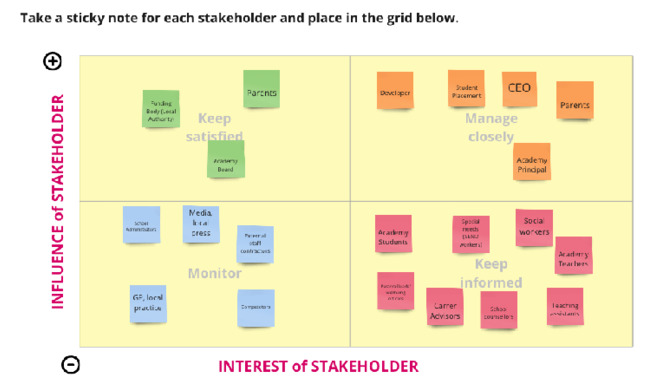

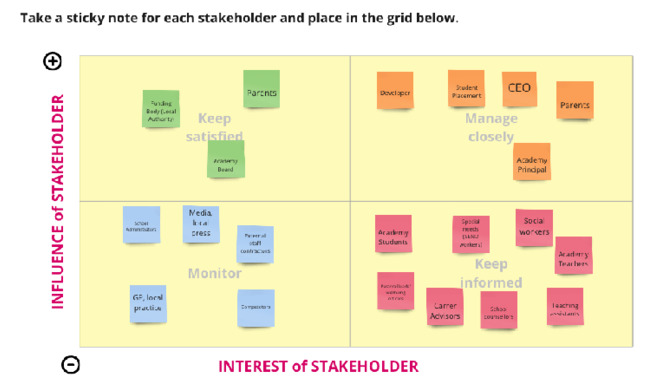

- Once the list of stakeholders is ready, ask the students to allocate each stakeholder according to one of the four categories.

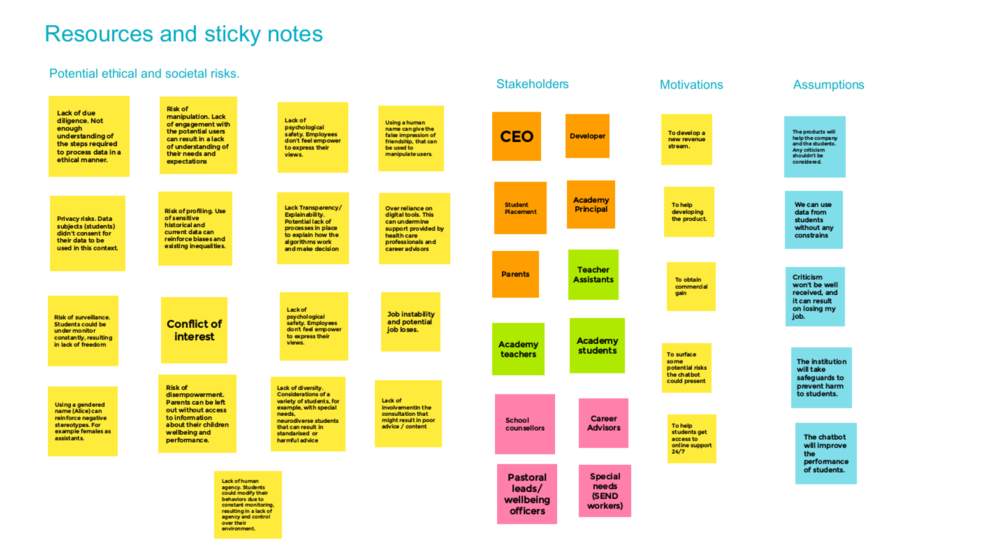

Board One

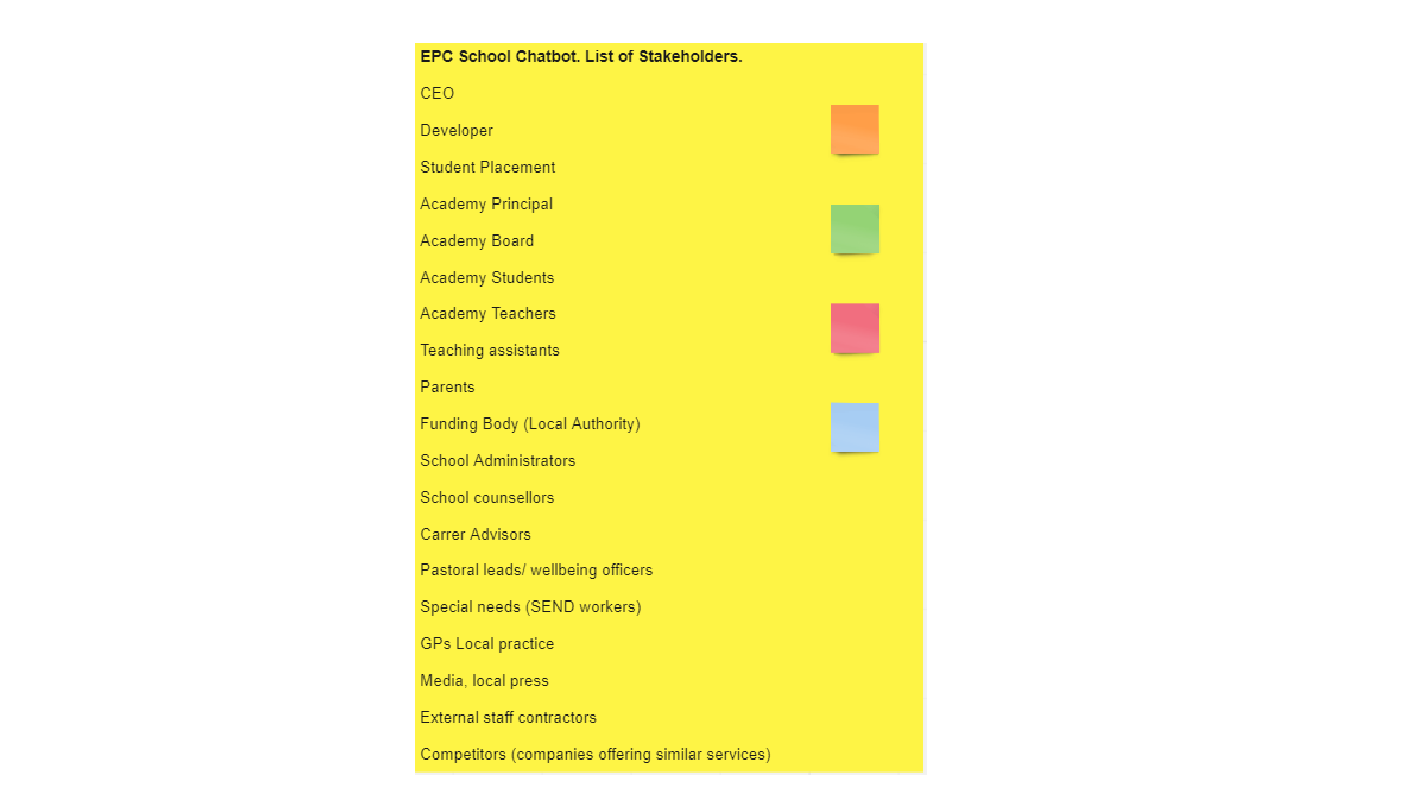

List of stakeholders:

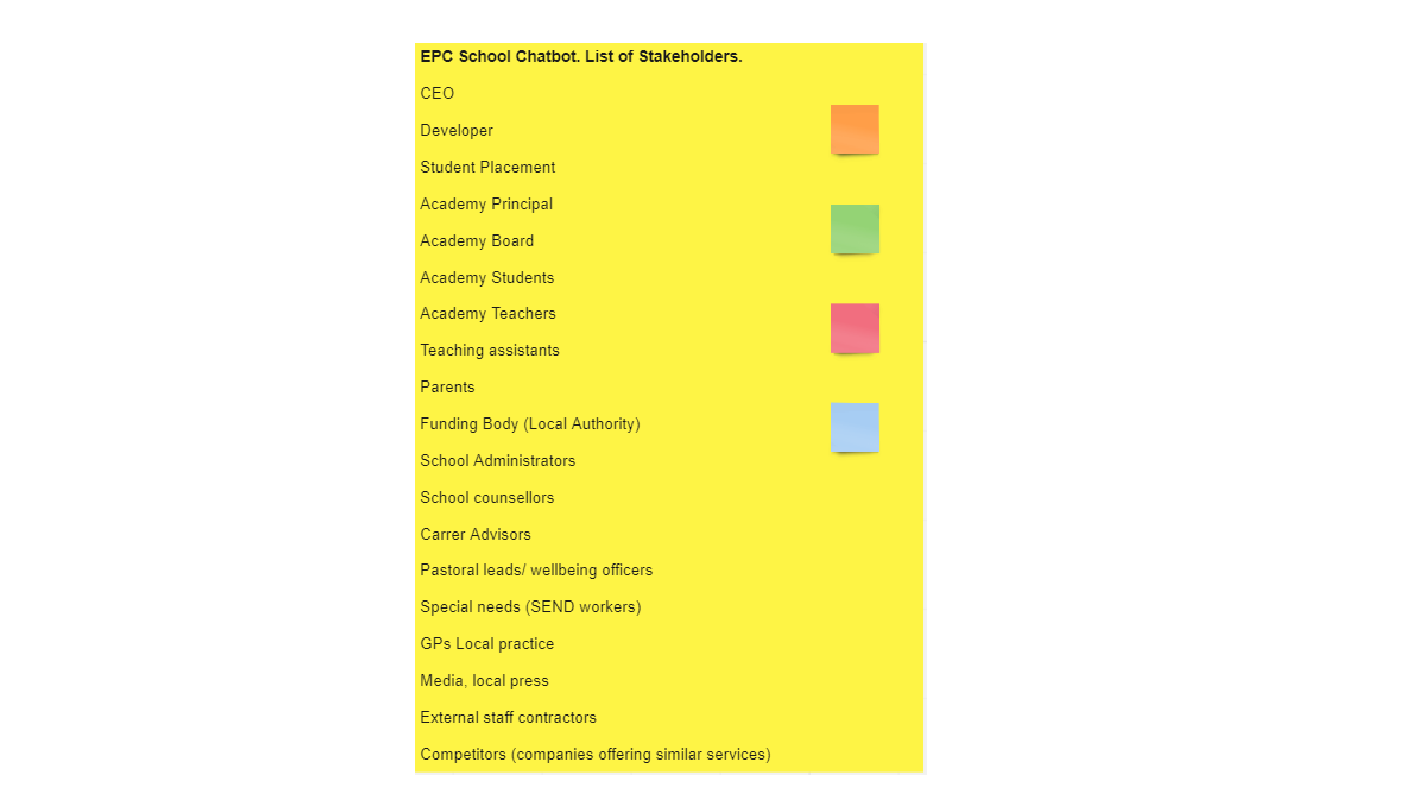

Below is a list of the stakeholders involved in the Chatbot project. Put each stakeholder on a sticky note and add them to the stakeholders map, according to their level of influence and interest in the projects.

Top tip: use a different colour for each set of stakeholders.

School Chatbot – List of Stakeholders:

-

- CEO

- Developer

- Student placement

- Academy principal

- Academy board

- Academy students

- Academy teachers

- Teaching assistants

- Parents

- Funding body (Local Authority)

- School administrators

- School counsellors

- Career advisors

- Pastoral leads/wellbeing officers

- Special needs (SEND) workers

- GPs local practice

- Media/local press

- External staff contractors

- Competitors (companies offering similar services).

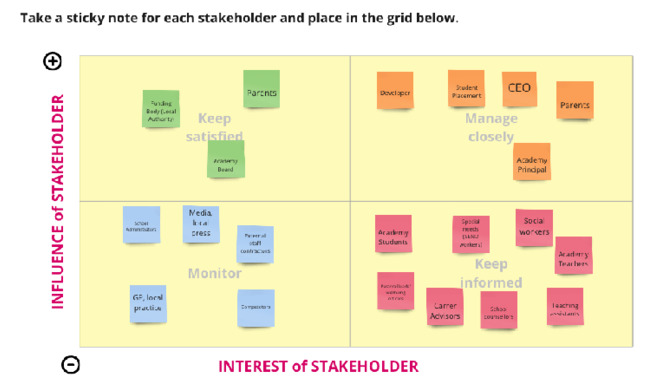

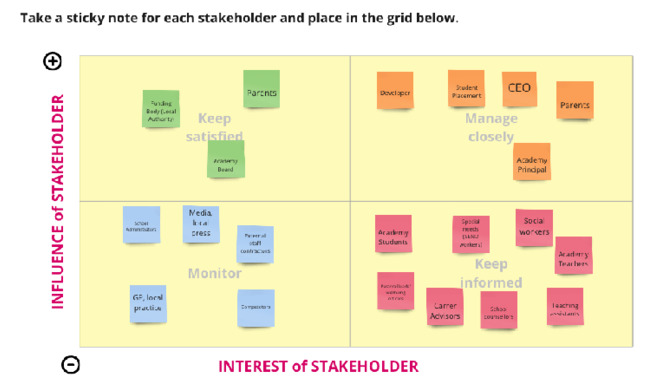

Placement:

- Place the sticky notes with the stakeholders you choose from the list and add them to the stakeholders’ map.

- Map out your stakeholders on the grid to classify them by both their influence and interest in the project.

- The position of the stakeholder on the grid shows you the actions that you could take with their engagement.

Guidance:

Each quadrant represents the following:

- Category: Manage closely. These stakeholders have high power and are highly interested. Their level of interest is an opportunity to maximise the benefit of the project.

- Category: Keep satisfied. These stakeholders have high power, but they are not very involved in the project.

- Category: Keep informed. These stakeholders have low power but high interest. They are supporters of the project and can be helpful. Keep them involved.

- Category: Monitor. These stakeholders have low power and low interest in the project. They only require monitoring.

Board One

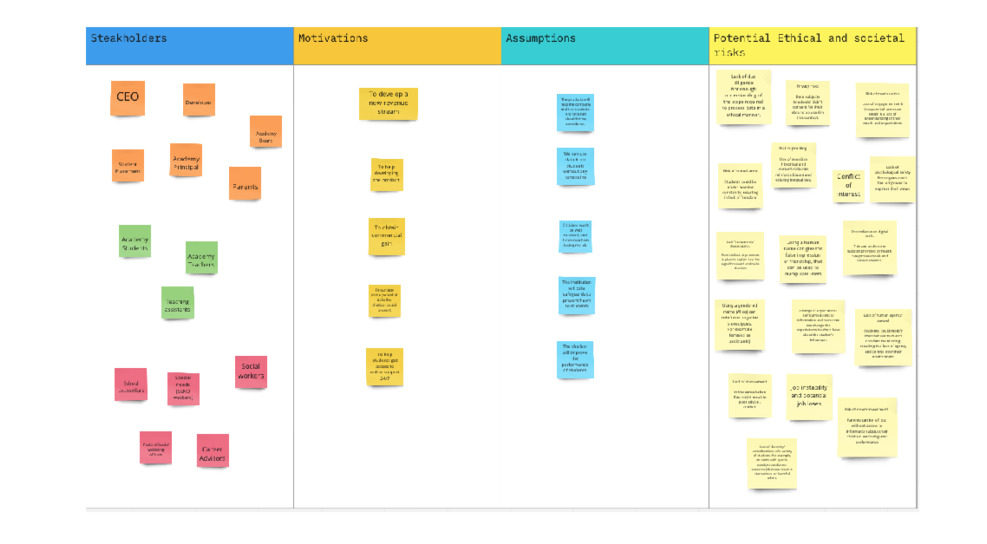

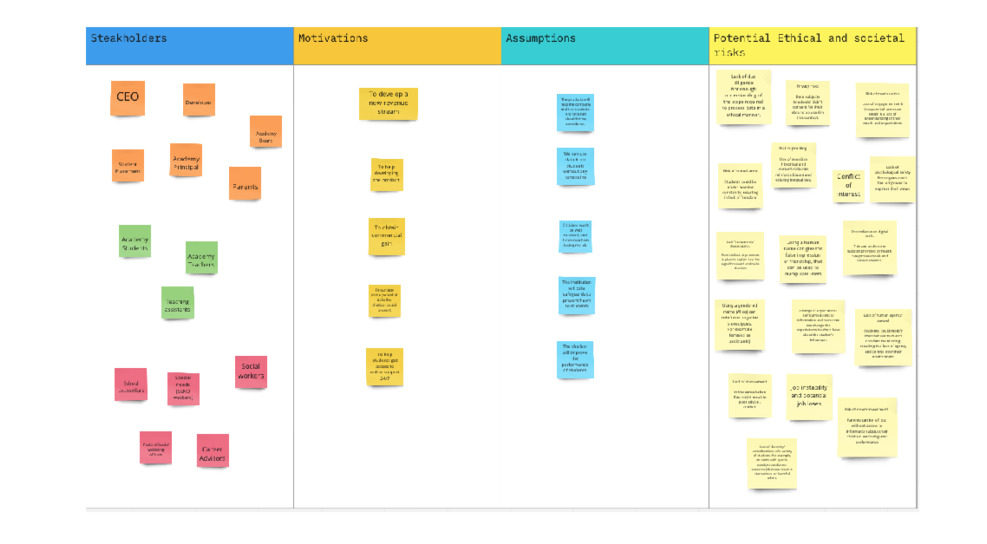

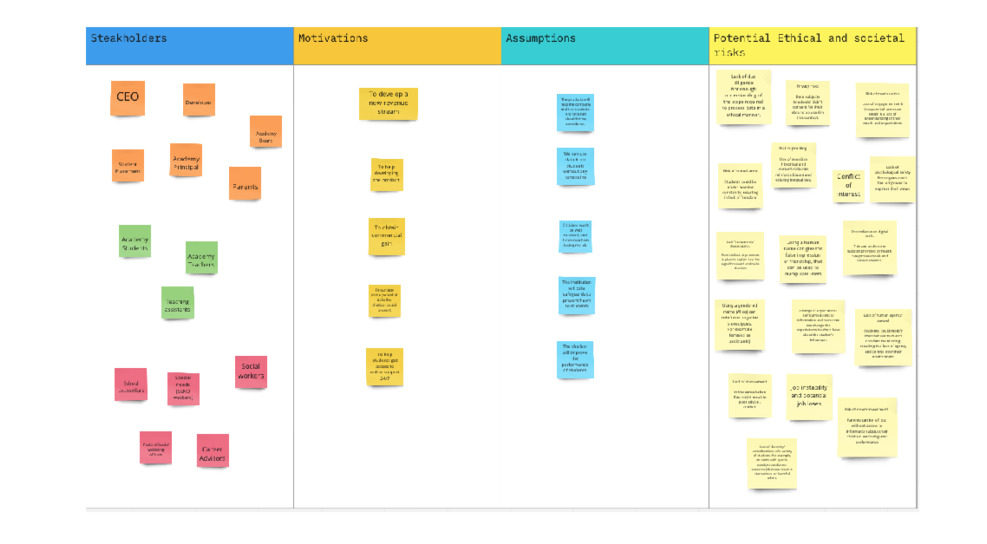

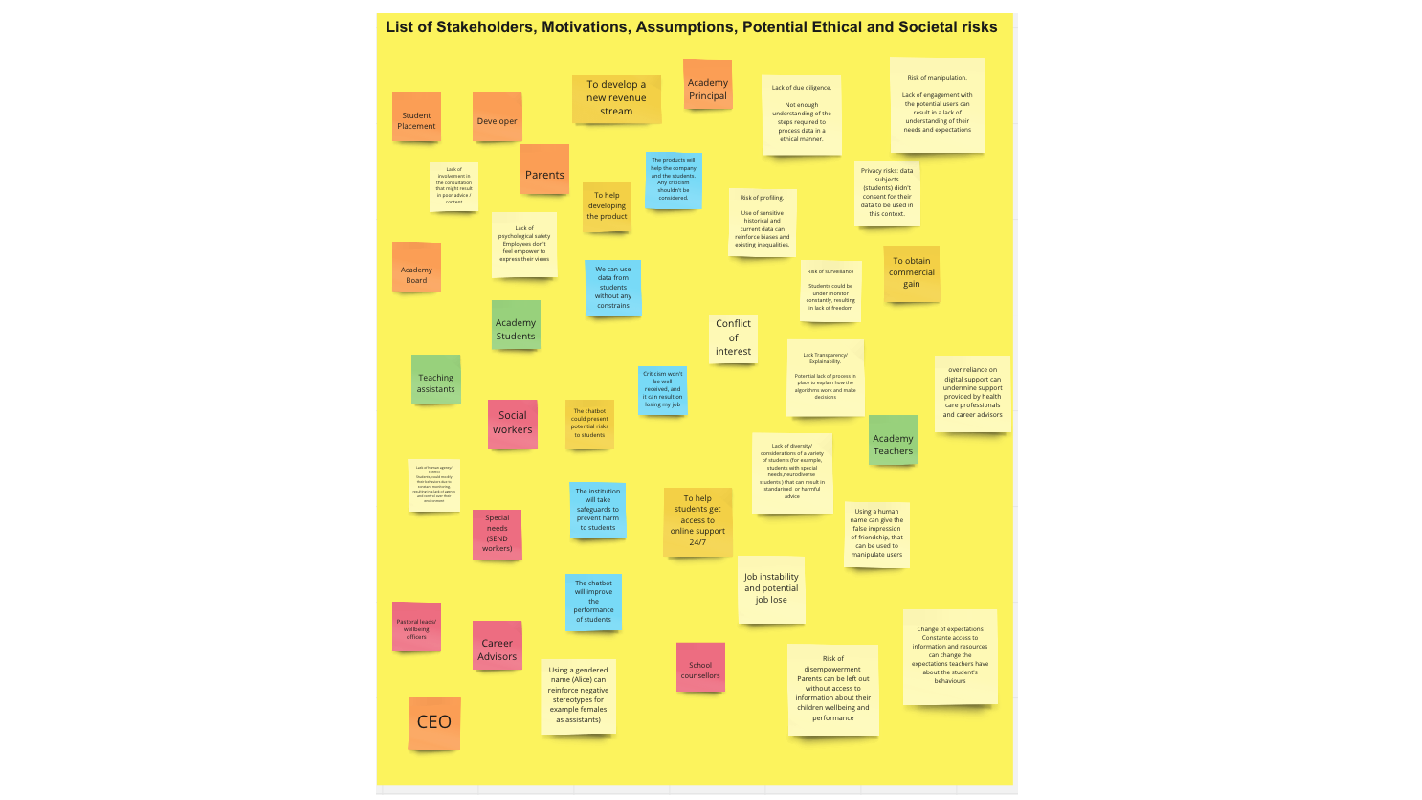

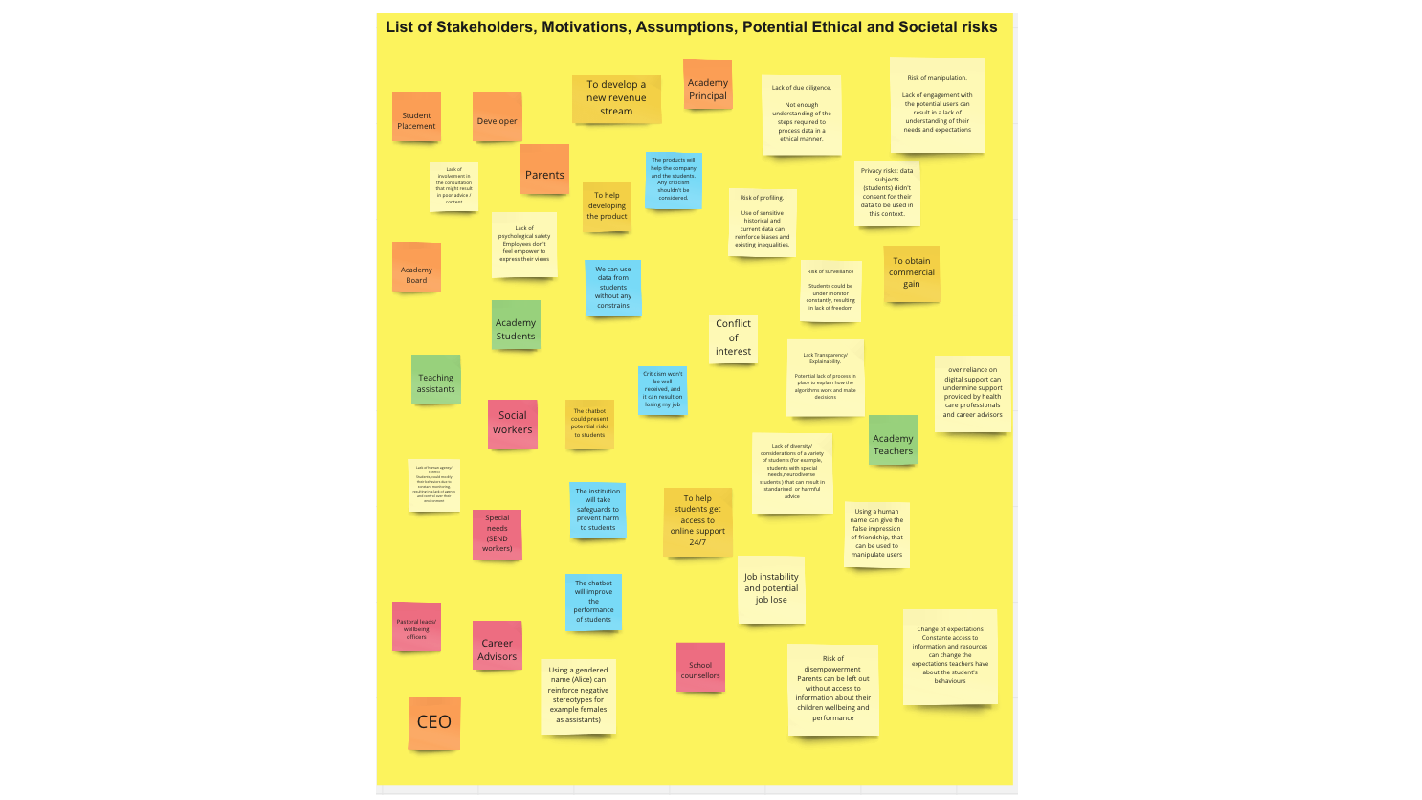

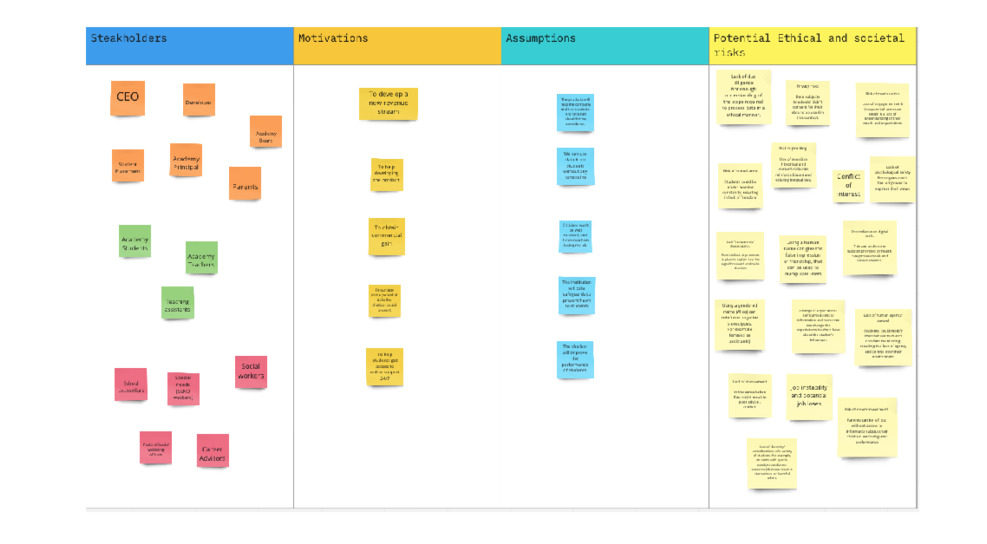

Motivations, assumptions, ethical and societal risks:

Materials:

1. A big piece of paper or digital board (Jamboard, Miro if online) divided into four categories:

-

- Stakeholders.

- Motivations.

- Assumptions.

- Ethical/societal risks.

2. Sticky notes (or digital notes if online).

3. Markers and pencils.

The activity:

- Using the sticky notes from the previous stakeholders activity, ask students to discuss some of the scenarios and situations that can arise as a result of using the School Chatbot.

- Ask students to write these scenarios down and add them to Board 2, according to each category: stakeholders, motivations, assumptions, and ethical and societal risks.

- Discuss some issues this project can bring and ask students to write them on sticky notes according to each category.

Board Two

The Board Two activity can be done in two different ways:

Option 1:

You can use some guiding questions to direct the discussion. For example:

- What role does stakeholder X play in this project?

- What is their main motivation?

- Can you think of any obstacle or conflict this stakeholder could face?

- What is their assumption about the use of the chatbot? (Positive or negative.)

- What are the potential ethical/ societal risks of using a chatbot in this context?

Option 2:

We have already written some assumptions, motivations and ethical/societal risks and you can add these as notes on a table and ask students to place according to each category: stakeholders, motivations, assumptions, and ethical and societal risks.

Motivations:

- To develop a new revenue stream.

- To help in developing the product.

- The chatbot could present potential risks to students.

- To obtain commercial gain.

- To help students get access to online support 24/7.

Assumptions:

- The product will help the company and the students. Any criticism shouldn’t be considered.

- We can use data from students without any constraints.

- The chatbot will improve the performance of students.

- The institution will take precautions to prevent harm to students.

- Criticism won’t be well received and it can result in losing my job.

Potential ethical and societal risks:

- Lack of due diligence. Not enough understanding of the steps required to process data in an ethical manner.

- Privacy risks. Data subjects (students) didn’t consent to their data being used in this context.

- Risk of manipulation. Lack of engagement with the potential users can result in a lack of understanding of their needs and expectations.

- Risk of surveillance. Students could be under constant monitoring, resulting in lack of freedom.

- Risk of profiling. Use of sensitive historical and current data can reinforce biases and existing inequalities.

- Conflict of interest.

- Lack of psychological safety. Employees don’t feel empowered to express their views.

- Lack of transparency/explainability. Potential lack of processes in place to explain how the algorithm works and makes decisions.

- Using a human name can give the false impression of friendship, which can be used to manipulate users.

- Over reliance on digital tools. This can undermine support provided by health care professionals and career advisors.

- Using a gendered name (Alice) can reinforce negative stereotypes (for example, females as assistants).

- Change of expectations. Constant access to information and resources can change the expectations teachers have about the student’s behaviours.

- Lack of human agency/control. Students could modify their behaviours due to constant monitoring, resulting in a lack of agency and control over their environment.

- Lack of involvement in the consultation that might result in poor advice/content.

- Job instability and potential job losses.

- Risk of disempowerment. Parents can be left out without access to information about their children’s wellbeing and performance.

- Lack of diversity/consideration of a variety of students – for example students with special needs, neurodivergent students – that can result in standardised or harmful advice.

Move and match:

- In the board below, you will find sticky notes with a list of stakeholders, motivations, assumptions, and ethical and societal risks.

- Move and organise the sticky notes to match each category.

- Discuss your options with the rest of the team and add new ethical and societal risks as you go.

Reflection:

Ask students to choose 2- 4 sticky notes and explain why they think these are important ethical/societal risks.

Potential future activity:

A more advanced activity could involve a group discussion where students are asked to think about some mitigation strategies to minimise these risks.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.