Author: Andrew Avent (University of Bath).

Author: Andrew Avent (University of Bath).

Keywords: Assessment criteria; Pedagogy; Communication.

Who is this article for? This article should be read by educators at all levels in higher education who wish to integrate ethics into the engineering and design curriculum, or into module design and learning activities. It describes an in-class activity that is appropriate for large sections and can help to provide students with opportunities to practise the communication and critical thinking skills that employers are looking for.

Premise:

Encouraging students to engage with the ethical, moral and environmental aspects of engineering in any meaningful way can be a challenge, especially in very large cohorts. In the Mechanical Engineering department at the University of Bath we have developed a debate activity which appears to work very well, minimising the amount of assessment, maximising feedback and engagement, and exposing the students to a wide range of topics and views.

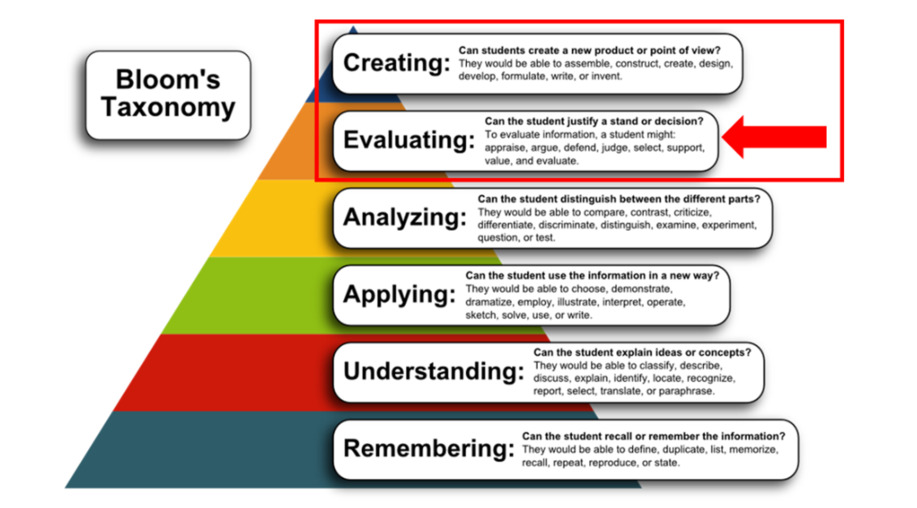

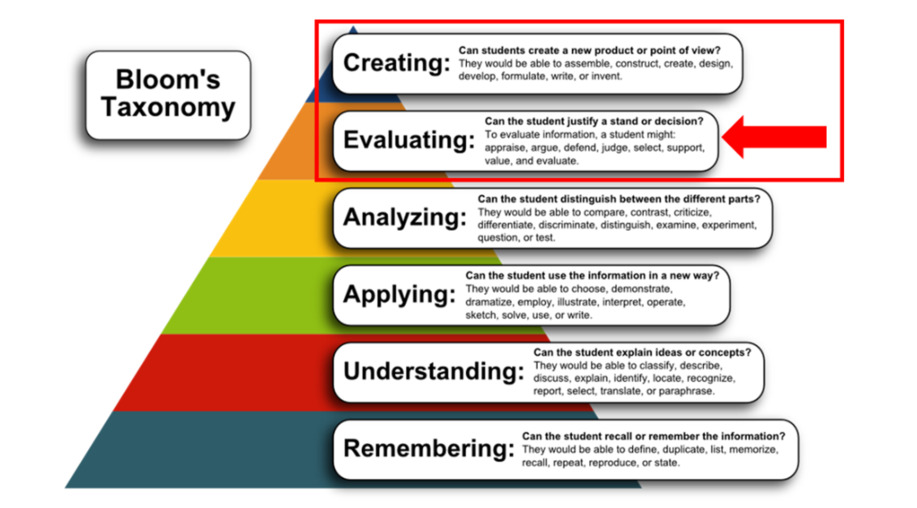

In our case, the debate comes after a very intensive second year design unit and it is couched as a slightly “lighter touch” assignment, ahead of the main summer assessment period. The debate format targets the deeper learning of Bloom’s taxonomy and is the logical point in our programme to challenge students to develop these critical thinking skills.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain.” New York: David McKay Co Inc.

This activity addresses two of the themes from the Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes (AHEP) fourth edition: The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

The debate format:

- Several weeks prior to the unit starting, academic staff are asked to submit ideas for technical engineering conundrums as topics for debate; the topics need to be current and include ethical, moral, environmental and technical feasibility aspects.

- The cohort is divided into randomly formed groups (aiming for six members in each). An even number of groups is essential (half being pro vs half being anti).

- Each pair of groups is assigned a debate topic, with odd numbered groups arguing in favour of the statement, even numbered groups arguing against.

- Each group then spends a couple of weeks researching the topic (we weave this in around Easter so the precise timings vary). Studio/tutorial sessions are used by the groups to (a) clarify the scope and intent of the question posed, (b) try out their arguments, and (c) obtain differing perspectives from academic support staff.

- We provide supporting lectures covering environmental considerations and commercial imperatives; there is scope to include ethical issues within this.

- On debate day the cohort is further divided so that we can run four concurrent debate sessions and keep the timings reasonable.

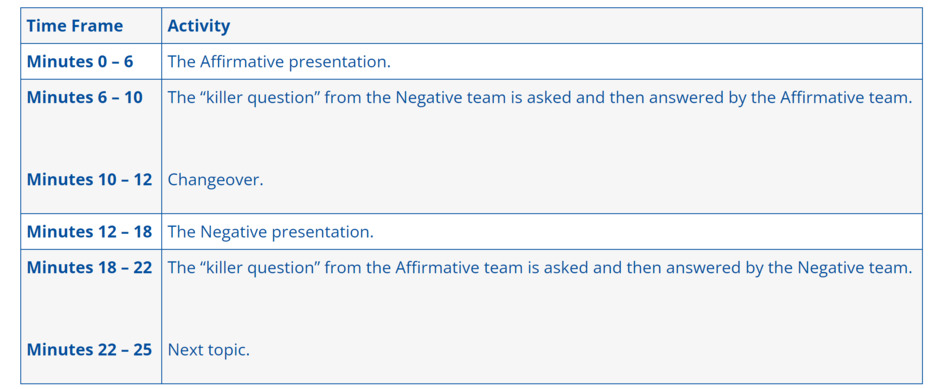

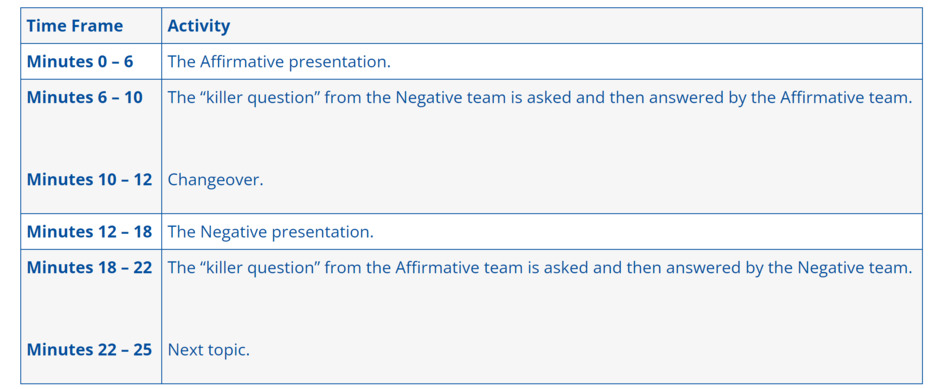

- Each debate room is set up with the two teams in a “v” formation facing each-other and the audience. The typical timings of a debate session are provided in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Timings for technical feasibility debate. There is plenty of scope to alter these timings

and allow a healthy debate from the floor and further exploration of the key arguments.

- The audience is asked to vote (using a QR code unique to each session) and the winning team is declared. The votes are revealed in real time and are displayed, adding an element of theatre.

- There are no marks on the debate at this stage; attendance is notionally compulsory but in fact we have near full attendance. In any event, the sense of anticipation, duty to one’s team and a desire to eavesdrop on colleagues’ debate tactics (arguments) drives the activity. Staff from across the department are invited to attend those sessions related to their interests and research; they often chime in with questions from the floor and provide an interesting perspective for the students to take into the final deliverable – a six-minute video presentation of their argument.

- The videos are marked by a panel of three academics (a number greater than three and there tends to be an inevitable dilution of marks at the extreme ends of the spectrum).

- Following marking, the videos are made available to the rest of the cohort (in our case, hosted on Panopto) so that they can further engage in topics of their choosing and understand why they were allocated the mark they were.

Some key points to bear in mind:

- The students do not get the opportunity to choose a topic or indeed which side of the argument they are required to argue. This is presented to the students by asking them to imagine they were a defence counsel at court, having to defend a notorious criminal; in order to ensure the safety of the conviction they would have to acquaint themselves with every weakness, every potential flaw in the prosecution’s case and to anticipate the “killer questions”. Take for example a team of engineering undergraduates who are all keen F1 enthusiasts and are placed in a position of having to take the negative position and argue against F1 as a sport (the actual debate topic is shown below).

The environmental impact of Formula 1 can(not) be justified through improvements to vehicle and other technologies.

For clarity, the term “Affirmative” means they are arguing for the proposal, “Negative” implies they are arguing against the proposal. The Negative argument includes the bracketed word in all cases.

Equally the team given the “affirmative” position to argue in favour of the sport, needs to be certain of their arguments and to fully research and anticipate any potential killer questions from their opponents.

- It will be seen that this challenges the students and indeed the audience (staff included) to confront some uncomfortable and inconvenient truths, exposing those present to the deeper research undertaken by the students in preparation for the debate as well as to the broader contexts of engineering and its macroethical implications.

- Asking for a video submission a few days after the debate forces the students to assimilate the counter arguments and update or revise their presentation and indeed potentially their entire approach.

- The first time this debate format was trialled was as an entirely online (remote) activity (forced upon us by the pandemic). Thanks to the sterling work on the requisite IT/AV side by colleagues (acknowledged below) it worked very well in this format and was universally acclaimed as a success by staff and students alike (receiving positive feedback and high unit evaluation scores). In this format it was a gruelling three and a half hour exercise, but it allowed students, who had hitherto been isolated from their wider cohort, to engage in the banter and atmosphere from afar. There was an element of student voting in this first iteration of this exercise and a real sense of healthy competition and energy.

Discussion points for improvements:

- The use of microphones in front of each team and for the session chair/MC would improve engagement from the entire audience.

- An element of peer marking might heighten engagement further but might also be problematic with students influencing the actual unit marks of their peers.

- Directly linking academic research and teaching material to the topics for debate might encourage a more engaged and critical cohort in later units and might also potentially send the students out on placement better prepared and more aware.

We felt that our experience with what has become known as the Technical Feasibility Debate was worth sharing with the wider higher education community, and hope that readers will learn from our experience and implement their own version.

Acknowledgements:

- Dr Joseph Flynn – unit convener and co-originator of the debate format.

- Dr Ed Elias – for his excellent lecture providing the students with some insight into the commercial imperatives impacting their arguments.

- Dr Rick Lupton – for his excellent lecture and supporting material giving the students an environmental and lifecycle analysis perspective to their arguments.

- Dr Nathan Sell – for his technical, IT and AV contribution (including the voting system) which made the new format possible.

- Dr Elies Dekoninck – as head of the design group in Bath for her encouragement and support in trialling these new approaches.

Appendices:

Typical list of debate topics:

- Gas turbines are (not) a dying technology for aircraft propulsion.

- Cumbrian super coal mine: there is (no) justification for accessing these fossil fuel reserves.

- Metal additive manufacturing, 3D Printing, is (not) a sustainable technology.

- Mining the Moon/asteroids for minerals, helium, etc. should (not) be permitted.

- Electrification of lorries via hydrogen fuel cell technology is (not) preferable to changing the road infrastructure to include overhead power lines (or similar).

- Electrification of road vehicles is (not) preferable to using cleaner fuel alternatives in internal combustion engine cars.

- The use of single use plastic packaging is (not) defensible when weighed up against increases in food waste.

- The environmental impact of Formula 1 can(not) be justified through improvements to vehicle and other technologies.

- Solar technologies should (not) take a larger share of future UK investment compared to wind technologies.

- Tidal turbines will (never) produce more than 10% of the UK’s power.

- Wave energy converters are (never) going to be viable as a clean energy resource.

- Commercial sailing vessels should (not) be used to transport non-perishable goods around the globe.

- We should (not) trust algorithms over humans in safety-critical settings, for example autonomous vehicles.

- Inventing and manufacturing new technologies is (not) more likely to help us address the climate emergency than reverting to less technologically and energy intense practices

- Mechanical Engineering will (not) one day be conducted entirely within the Metaverse, or similar.

- The financial contribution and scientific effort directed towards fundamental physics research, for example particle accelerators, is (not) justified with regard to the practical challenges humanity currently faces.

- A total individual annual carbon footprint quota would (not) be the best way to reduce our carbon emissions.

- The UK power grid will (not) be overwhelmed by the shift to electrification in the next decade.

- We are (not) more innovative than we were in the past – breakthrough innovations are (not) still being made.

- Lean manufacturing and supply chains have (not) been exposed during the pandemic.

Marking rubric:

| Criteria | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 1. Organisation and Clarity:

Main arguments and responses are outlined in a clear and orderly way. |

Exceeds expectations with no suggestions for improvement. | Completely clear and orderly presentation. | Mostly clear and orderly in all parts. | Clear in some parts but not overall. | Unclear and disorganised throughout. |

| 2. Use of Argument:

Reasons are given to support the resolution. |

Exceeds expectations with no suggestions for improvement. | Very strong and persuasive arguments given throughout. | Many good arguments given, with only minor problems. | Some decent arguments, but some significant problems. | Few or no real arguments given, or all arguments given had significant problems. |

| 3. Presentation Style:

Tone of voice, clarity of expression, precision of arguments all contribute to keeping audience’s attention and persuading them of the team’s case. Neatly presented and engaging slides, making use of images and multimedia content. |

Exceeds expectations with no suggestions for improvement. | All style features were used convincingly. | Most style features were used convincingly. | Few style features were used convincingly. | Very few style features were used, none of them convincingly. |

References:

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.