Toolkit: Complex Systems Toolkit.

Author: Nafiseh M. Aftah, PhD Candidate (University of Kansas).

Topic: Why integrate complex systems in engineering education?

Title: Complex systems in a transformational era.

Resource type: Knowledge article.

Relevant disciplines: Any.

Keywords: Interdisciplinarity; Problem-solving; Problem-based learning; Active learning; Professional development; Collaboration; Real world; Artificial Intelligence; Trade offs.

Licensing: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Downloads: A PDF of this resource will be available soon.

Who is this article for?: This article should be read by educators at all levels in higher education who are seeking an overall perspective on teaching approaches for integrating complex systems in engineering education.

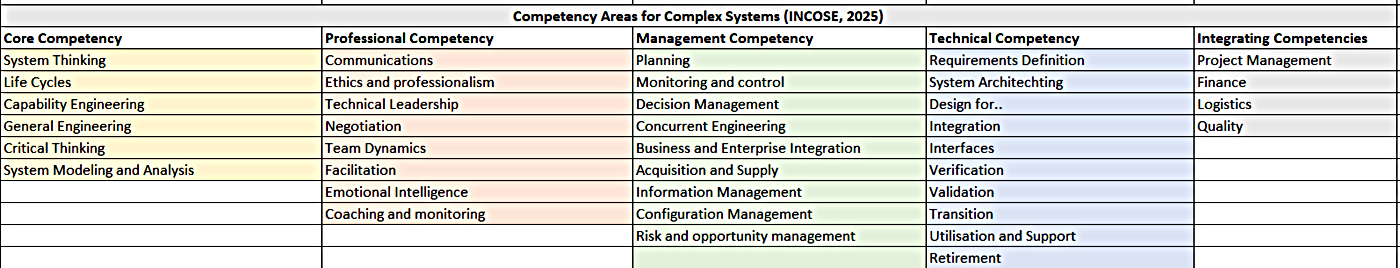

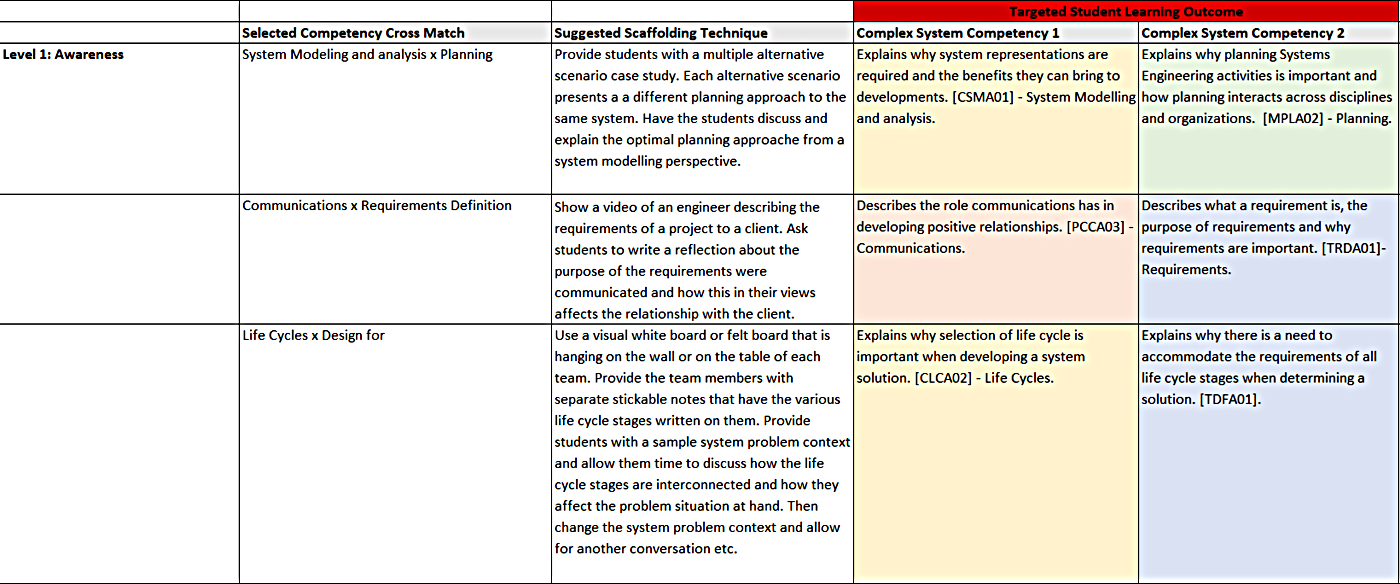

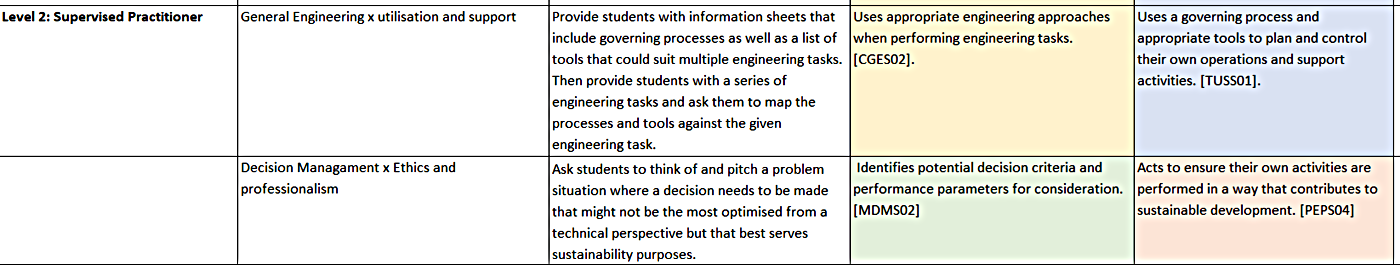

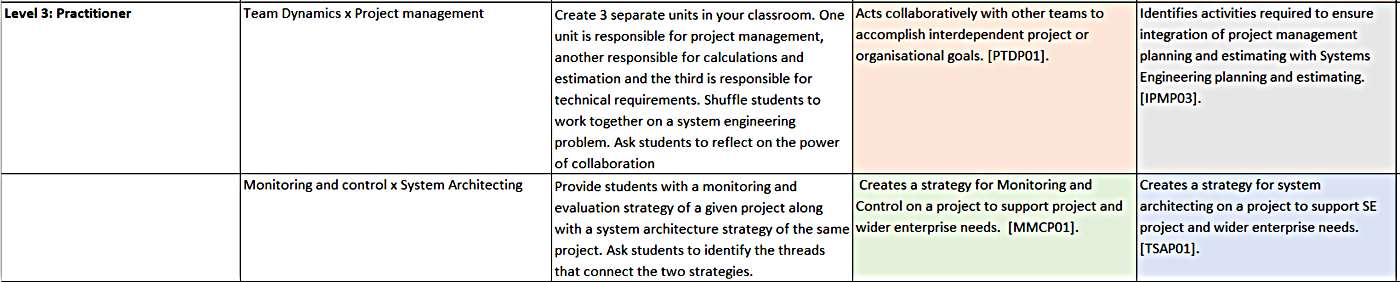

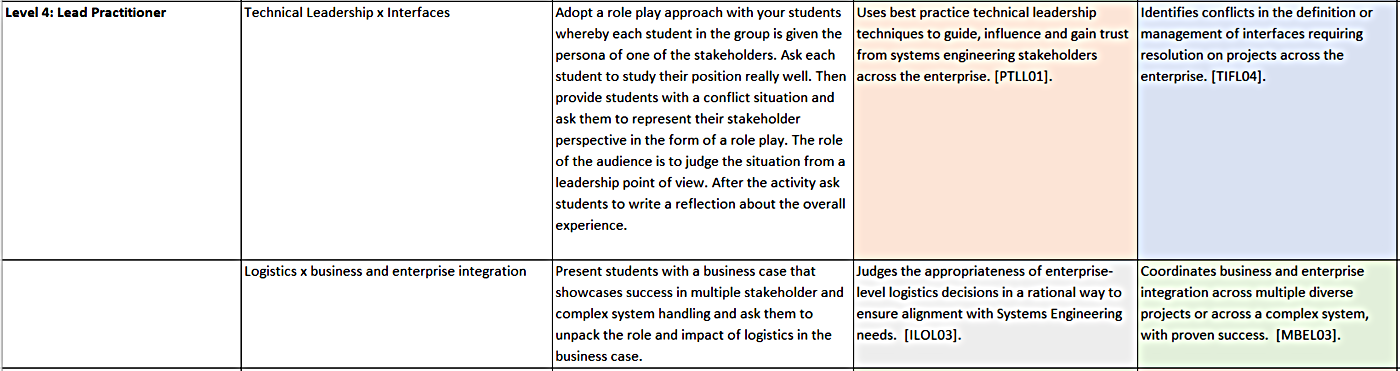

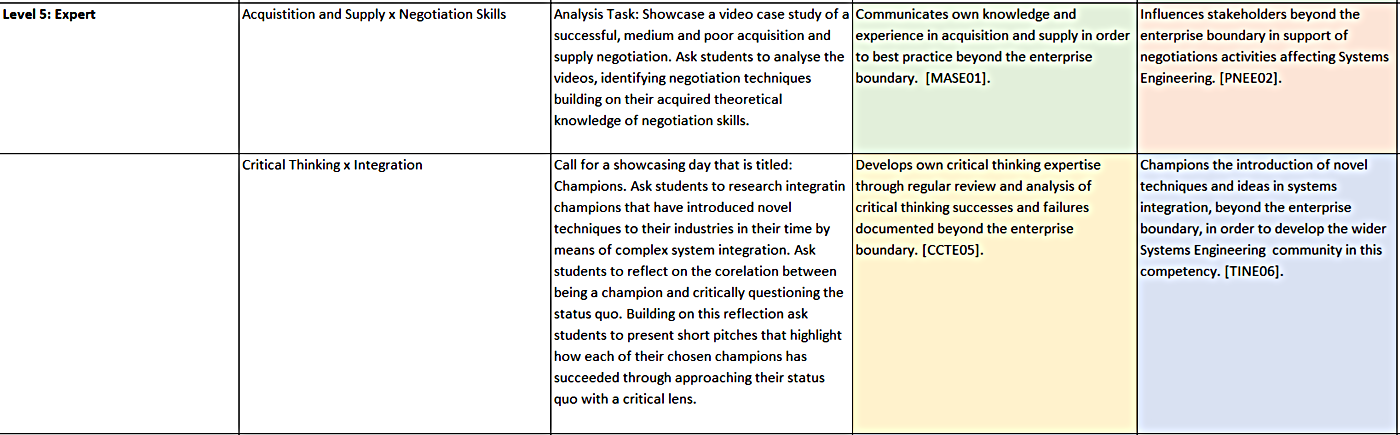

Related INCOSE Competencies: Toolkit resources are designed to be applicable to any engineering discipline, but educators might find it useful to understand their alignment to competencies outlined by the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). The INCOSE Competency Framework provides a set of 37 competencies for Systems Engineering within a tailorable framework that provides guidance for practitioners and stakeholders to identify knowledge, skills, abilities and behaviours crucial to Systems Engineering effectiveness. A free spreadsheet version of the framework can be downloaded.

This resource relates to the Systems Thinking and Critical Thinking INCOSE competencies.

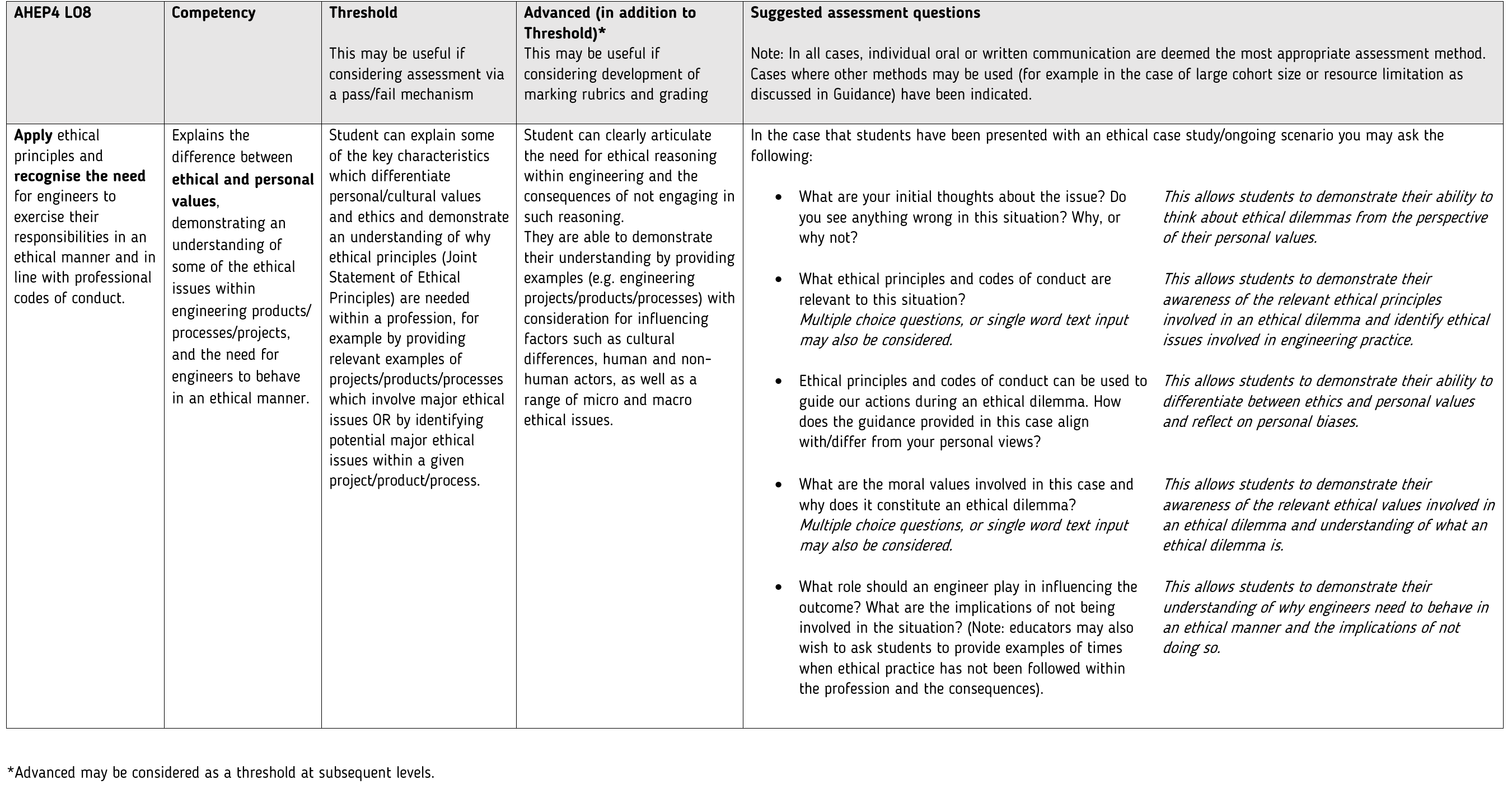

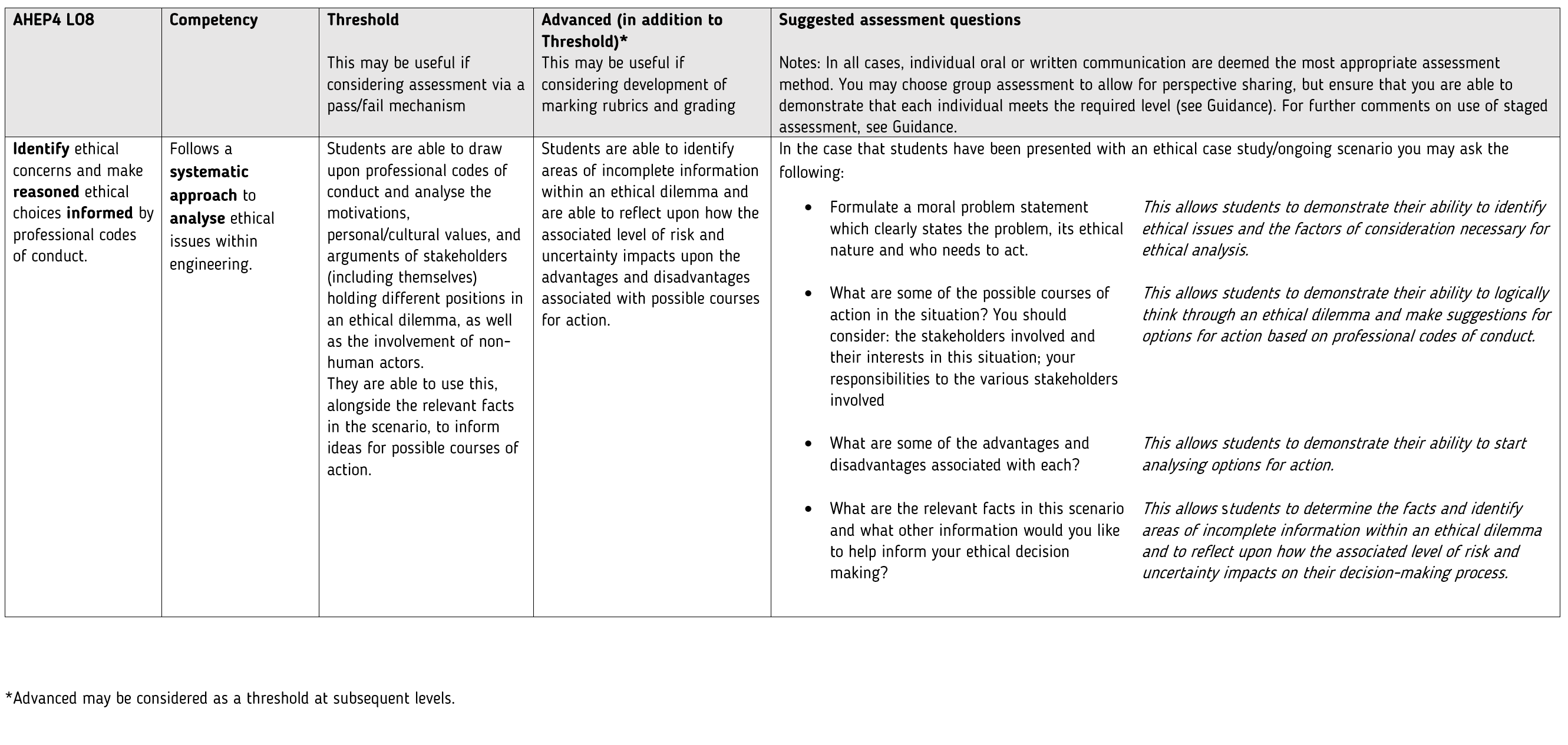

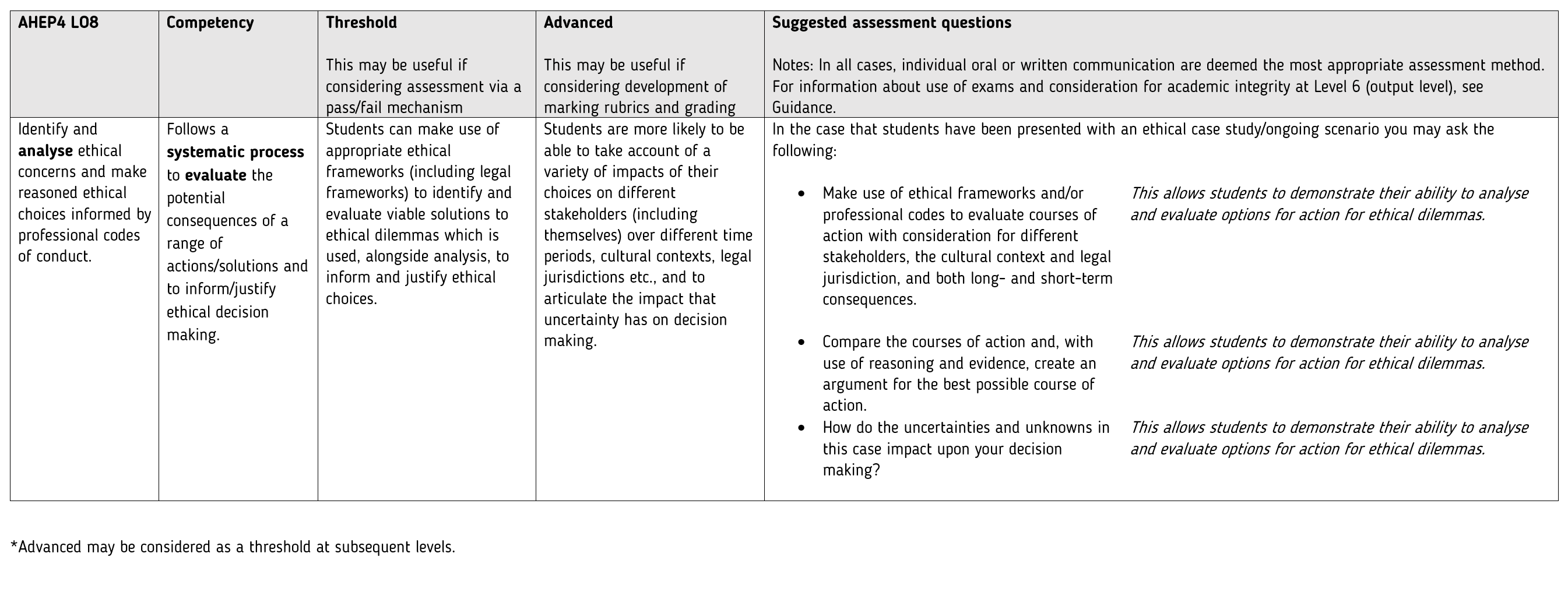

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses several of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): Analytical Tools and Techniques (critical to the ability to model and solve problems), and Integrated / Systems Approach (essential to the solution of broadly-defined problems).

Premise:

Engineering education is undergoing a fundamental transformation. The convergence of technological, social, and environmental challenges demands that future engineers move beyond procedural problem-solving toward complex thinking – a mindset capable of navigating uncertainty, interdependence, and dynamic change. This shift has been accelerated by advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI), which have redefined both the nature of engineering practice and the competencies students must develop to thrive in it.

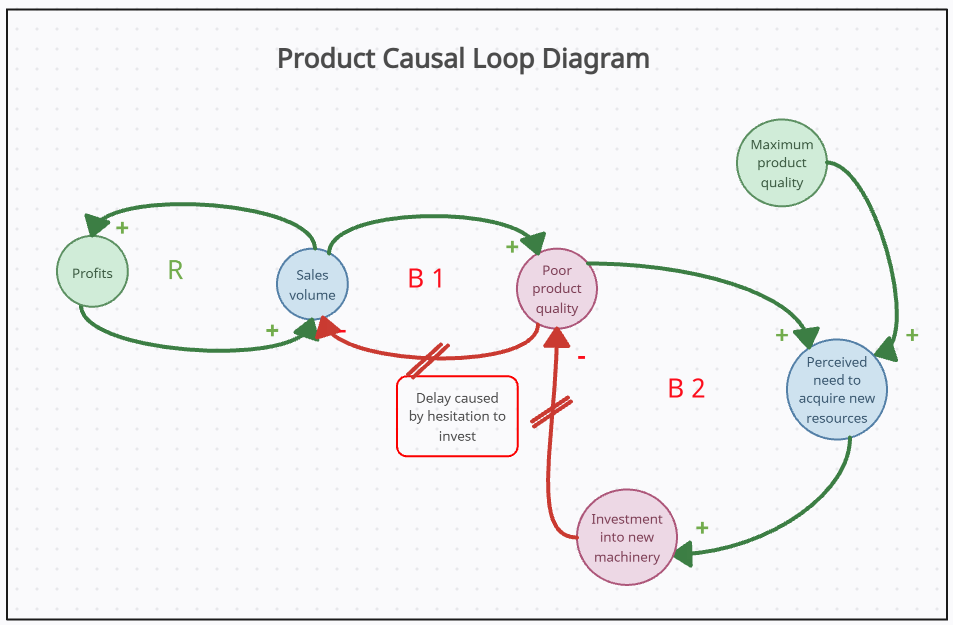

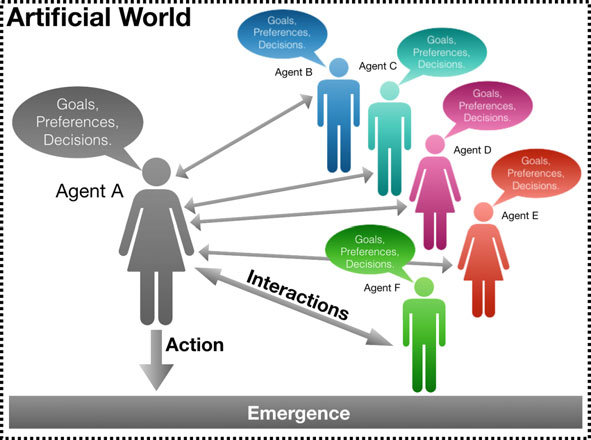

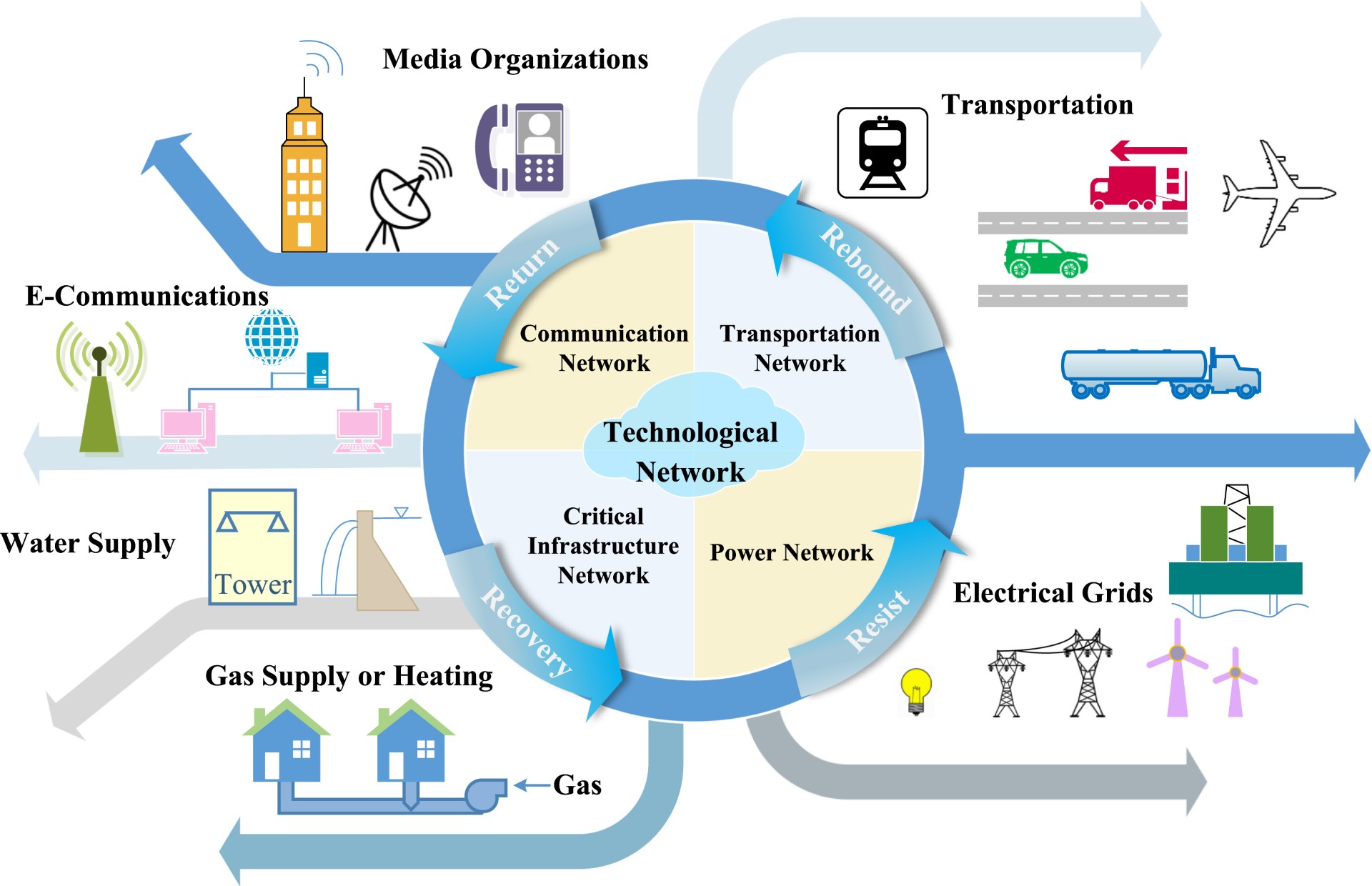

For scientists and engineers, understanding complex systems is critical for the ability to apply knowledge and techniques across diverse contexts. This is particularly visible in fields such as bioengineering, which depends on advances in chemistry, physics, computing, and other engineering disciplines. Such integration requires designing subsystems where engineering expertise can be meaningfully applied. Complex systems also involve human interaction, introducing unpredictability, feedback loops, and uncertainty. Modern AI-enabled systems—ranging from autonomous vehicles to smart grids and biomedical devices—cannot be fully understood through a single traditional discipline. These systems are not simply complicated; they are interconnected, dynamic, and often nonlinear (Jakobsson, 2025).

What this means for engineering education and educators:

Across the globe, educators have turned to Problem-Based Learning (PBL) as a central strategy for cultivating systems-oriented thinking. For instance, Tauro et al. (2017) and the case study conducted at Tishk International University demonstrate that integrating PBL within mechatronics education enhances students’ ability to connect theory with practice, encouraging collaboration and creativity in addressing multifaceted engineering problems. Similarly, Watters et al. (2016) show that industry–school partnerships transform classrooms into real-world laboratories, reinforcing the value of experiential learning and knowledge transfer between academia and professional practice. These initiatives reflect a broader movement toward authentic, interdisciplinary engagement, a necessary foundation for understanding and designing complex systems.

However, adopting PBL and interdisciplinary methods is not only a pedagogical improvement but also an epistemological necessity. As Stegeager et al. (2024) emphasise, educators themselves must evolve from instructors to facilitators, cultivating reflective and adaptive learning environments that mirror the complexity of professional engineering contexts. Mynderse et al. further highlight that when students are given responsibility for solving open-ended problems, they report higher satisfaction and deeper conceptual integration. These outcomes suggest that active learning approaches foster the kind of complex, interconnected reasoning required for contemporary engineering practice.

In parallel, the AI-driven classroom is transforming the educational landscape. Emerging evidence shows that generative AI tools support personalised learning and immediate feedback, freeing educators to focus on mentorship and creativity (Jaramillo, 2024). Yet this technological advancement also underscores the limits of automation. Machines can model and predict, but they cannot interpret ethical implications, reconcile trade-offs, or integrate human and ecological perspectives. This is where complex thinking becomes indispensable: it enables learners to understand AI not merely as a computational tool but as a component within broader sociotechnical systems.

The need for complex systems understanding is especially acute in fields such as bioengineering and mechatronics, where technologies intersect with living systems and social contexts. The defining feature of complex systems is the interaction among multiple components that produce emergent, often unpredictable behaviour. For engineering students, grasping these principles means developing the ability to think beyond linear causality and to engage with feedback loops, uncertainty, and adaptive design.

The imperative to transform engineering education:

In traditional engineering education, students get topics presented in discrete classes. They get trained in thermodynamics and fluid mechanics and they often forget what they have learned by the time they are at the control systems course where there is an opportunity to bring together skills from prior knowledge. This modularised model is already losing its effectiveness in preparing the students for encountering real-world problems. As the adage says, “In theory, theory and practice are the same; in practice, they are not”. Understanding the role of noise, measurement errors, simplifying assumptions and computational errors play an essential role. To this end, it is crucial to centre complex system design and embrace interdisciplinarity to develop a competency that supports life-long, adaptive learning.

As an example, Aalborg University in Denmark stands as a global exemplary of systems-oriented engineering education. Its PBL model is not an add-on; it is the spine of the entire curriculum. Every semester, students tackle a new problem – often tied to societal needs such as urban planning, environmental sustainability, or healthcare. Students must identify relevant knowledge areas, work collaboratively across disciplines, and reflect on both process and outcome. Faculty report that this structure promotes holistic thinking, resilience, and a sense of professional identity early on the students’ journeys (Kolmos et al. 2008).

On the undergraduate level, capstones are a common part of engineering education which happens at the late stages of the student’s studies. At Rowan University (New Jersey, USA), Engineering Clinics provide a different but equally powerful model. Students work across all four years on interdisciplinary teams, contributing to faculty research or industry-sponsored projects. These clinics are embedded in the curriculum and require students to engage deeply with current research problems, often involving complex technical and human systems. A junior clinic project, for example, might involve the optimisation of a renewable energy system integrating mechanical, electrical, and computer engineering principles. Therefore, students learn to navigate ambiguity, collaborate with experts, and see the relevance of their disciplinary knowledge in a broader context by confronting the messy nature of real data.

These are two of many examples where systems thinking is cultivated. Students gain exposure to open-ended problems and practice seeking connection across domains as they encounter the limits of their knowledge. In this fast-moving era, crossing disciplines empowers students for lifelong adaptation, allowing them to incorporate their experiences into any new technological developments. It also encourages treating learning as a collaborative social process, rather than a solo race to secure the first job.

Educators must do more than just deliver content; they also need to act as facilitators and learn alongside their students. By redesigning the curriculum around design-oriented problems that mirror real-world changes, higher education will better prepare future engineers to face upcoming systemic global challenges.

Looking ahead:

As artificial intelligence and automation continue to reshape industry, engineering education must also evolve. Integrating complex systems into teaching offers students the opportunity to engage directly with the data-driven ecosystem they will encounter in practice. The goal is not only to produce technically skilled engineers, but also thoughtful stewards of technology who can navigate its broader social and ethical dimensions.

One ongoing challenge is that independent projects often vary in quality and can be difficult to assess. Without intentional design, students may default to trial-and-error approaches instead of drawing on knowledge from prior courses. At the same time, the pressure to cover extensive technical material can make it difficult to provide the broader systems context essential for modern engineering. Yet when learning is reinforced across the curriculum, students are better prepared for future careers that demand systems-based thinking.

Experiential, self-directed projects play a crucial role in this preparation. They allow students to choose their own path while working closely with advisors and industry partners. Whether developing a product, designing a system, or engaging with professionals, students gain a perspective that feels different from traditional coursework. This process offers them a glimpse of what it means to think and act like real engineers, fostering both confidence and adaptability as they transition from the classroom to the workplace.

References:

- Jakobsson, Eric et al. (1999) ‘Complex systems: Why and what?’, New England Complex Systems Institute. Available at: https://necsi.edu/complex-systems-why-and-what (Accessed: 16 July 2025).

- Jaramillo, J., Chiappe, A. (2024) ‘The AI-driven classroom: A review of 21st century curriculum trends’, Prospects. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11125-024-09704-w (Accessed: 1 August 2025).

- Kolmos, A., Du, X., Holgaard, J., Jensen. (2008) ‘Facilitation in a PBL environment. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338698720_Facilitation_in_a_PBL_environment (Accessed: 30 July 2025)

- Mynderse, James A., Shelton, Jeffrey N., (2014) ‘Implementing problem-based learning in a senior/graduate mechatronics course’, Paper presented at 2014 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Indianapolis, Indiana. Available at: https://peer.asee.org/implementing-problem-based-learning-in-a-senior-graduate-mechatronics-course (Accessed: 1 August 2025).

- Stegeager, N., Traulsen, S., Carvalho Guerra, A., Telléus, P., Du, X. (2024) ‘Do good intentions lead to expected outcomes? Professional learning amongst early career academics in a problem-based program’, Education Sciences, 14(2), p. 205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020205.

- Tauro, F., Cha, Y., Rahim, F., Rasul, M.S., Osman, K., Halim, L., Dennisur, D., Esner, B., Porfiri, M. (2017) ‘Integrating mechatronics in project-based learning of Malaysian high school students and teachers’, International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306419017708636 (Accessed: 1 August 2025).

- Watters, J., Pillay, H. and Flynn, M. (2016) ‘Industry-school partnerships: A strategy to enhance education and training opportunities. Australia’, Queensland University of Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/98390/ (Accessed: 30 July 2025).

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.