Elizabeth Robertson, Teaching Fellow in the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at The University of Strathclyde, discusses how we need to move past our discomfort in order to teach ethics in engineering.

Elizabeth Robertson, Teaching Fellow in the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at The University of Strathclyde, discusses how we need to move past our discomfort in order to teach ethics in engineering.

I could wax lyrical about the importance of engineering ethics for today’s students who are tomorrow’s engineers. However, there are lots of other articles that will do it much better than I can. All I’d say in short is that as educators, we know it’s important, our graduate employers tell us it’s important, and our accrediting bodies are looking for us to include it through our curriculum because they know it’s important too.

The task for us as educators then is to demonstrate the importance of ethics to our students and to offer students a learning experience that is relevant to them at whatever stage they are and that that will also offer the most impact – but as with so many things, that is easier said than done.

Getting comfortable with what the toolkit is and how to use it

I have used the Engineering Ethics Toolkit since its launch, and I cannot be a bigger proponent for its usefulness for staff or its impact on students’ learning. Educators are always challenged to design sessions that are engaging, participatory and have real student impact. With its range of case studies and really useful advice and guidance documents, the Engineering Ethics Toolkit does all three.

The documentation in the toolkit contains a mix of introductory material on what ethics is and why to integrate ethics education into modules alongside practical considerations including the ‘hows’ – best practice in teaching ethics and methods for assessment and evaluation.

Choosing a case study for your students

The suite of broad engineering ethics case studies means that there is a case study for a range of student needs (and there are often new ones on the horizon too). In my teaching that means sometimes I use case studies that are related to discipline-specific learning the students are currently undertaking so they can pull in technical knowledge and experience they have, and in other cases I choose something totally removed in order to allow students to spend more time with the ethical dimensions of a case and not get preoccupied with the technical.

The case studies I’ve used

During the last academic year we used the case study ‘Glass safety in a heritage building conversion’ with my first year groups, and that’s pretty far removed from the electrical, mechanical and computer science modules they take. That decision was intentional; the aim was to get students to concentrate on the principles of ethics, stakeholder mapping, stakeholder motivations and interpersonal dynamics and not be ‘distracted’ by the technical aspects. This was one class in a module centred around a sustainable design challenge and we used the Ethics toolkit to help students develop an understanding of the importance of economic, environmental and social factors. Working with a case study not in their exact engineering field helped students see that they must look beyond the technical to understand people – be they stakeholders, end users or community members. Students worked to make decisions on actions with honesty and integrity and to respect the public good. The students engaged really well in the session and there were some vibrant discussions on which actions were ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ and vitally the students grasped how stakeholder dynamics and dynamics of power in projects can affect outcomes.

In comparison, for my third year undergraduate students I intentionally chose a case study that would link to their hardware/software project that was upcoming, and connect closely to learning in their communications module: ‘Smart homes for older people with disabilities’. This meant that alongside stakeholder mapping we identified technical factors looking into possible routes of data leaks. Students engaged so well and were actively debating possible actions to take covering ethical, technical and legal implications. It pained me every time I had to cut conversations short so we could cover the full case study – so much so that this year we’re going to try and give them longer than an hour for the process.

Getting comfortable with the students in the lead

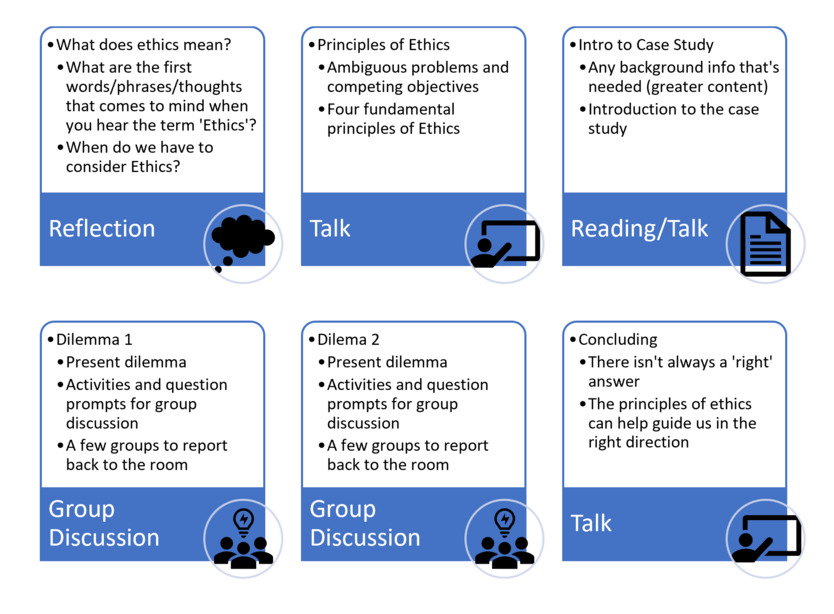

I use a participatory teaching methodology often. This means starting our 50 minutes together with student reflection, having 5/10 minutes of introductory talk and then rounds of group discussions. The students are therefore in the driving seat in the classroom – students set the tone and the pace. If they are having valuable, meaningful and worthwhile discussions and demonstrating valuable ethical discussions, my plans change. This means maybe not covering all parts of the case study maybe skipping a stage or two of discussions that were in my plans. As long as the session’s objective are met, the students can write their own journey.

What my sessions look like

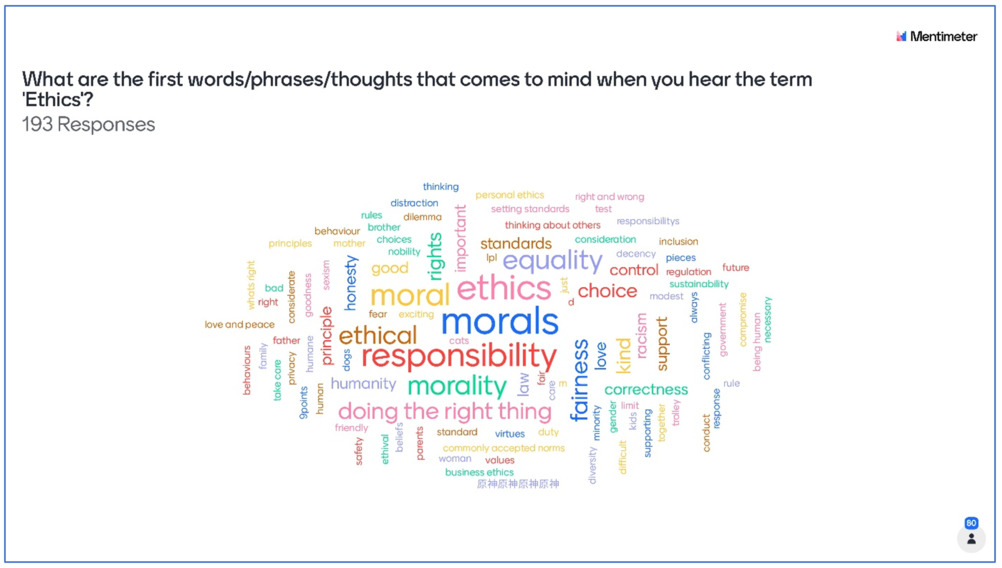

As the song goes, we start at the very beginning as it’s a very good places to start. That means first asking the students their current understanding of what ethics is – we did this first by using a word association activity, and asked what came to mind when they hear the term ‘ethics.’ Their answers in the word cloud below demonstrate a good maturity of thought to work from in the session. We then moved on to discuss when we should consider ethics – for us as individuals, members of society and as engineers.

What they said:

Building on from our prompting questions we then introduced the Statement of Ethical Principles published by the Engineering Council and the Royal Academy of Engineering and covering the four fundamental principles of ethics defined therein.

From there we worked with the toolkit and our case study of choice. Most case studies come in 2-4 ‘phases’, each with a bit more of the story that I’d briefly talk over, which we gave them printed and electronically. The phases often include a ‘dilemma’ for the protagonist and some questions for provoking thought and discussion or more technical work as is suitable. The questions and activity prompts that are within the case studies are invaluable to educators and students in helping design the session and for giving student groups a place to start if they are not sure how to tackle part of the story. We worked on a think-pair-share model asking individuals to think, groups to discuss, and then asking a few groups to report back to the room. One thing I want to do more of is asking different groups to role play as different stakeholders. Asking students to embed themselves in different perspectives can lead to some very valuable insights.

Getting comfortable in a room of differing views

Students worked in small groups with the case study and an important stage was asking groups to report back their thoughts. These were volunteered rather than cold-called and in asking for more groups to share I would prompt if anyone had a different view to make sure that a range of perspectives were heard. Though in fairness to the students they engaged so readily and enthusiastically that I often ran short of time rather than being left with ‘dead air’.

I have delivered ethics sessions to groups of 12, 30 and 100. In all cases it is important that all students feel heard and all views and perspectives respected. You need to make sure that an open, honest, and non-judgemental tone is set. This allows all students to feel they are free to ask questions and importantly share their perspectives, meaning that there is a big onus on the educator to act as a facilitator as much as a teacher.

Good facilitation is key. Some things to think about:

- Consider room layout. – Flexible seating in small groups has worked best for me. If I’m not using the whole space I place resources (printouts of the case study) on the tables I want used so no-one is left alone at the back of the room.

- How do you build discussion groups? – Will established (friendship) groups all agree with each other and therefore discussions die, or will their knowledge of each other help them challenge each other?

- How can you engage the whole room? – Cold-calling can challenge a neurodiverse audience, and so you need to consider ways to include everyone in discussions, but not put anyone on the spot.

- How do you set the right tone? – This enables discussions to be open and honest and allows all voices and perspectives to be heard.

Getting comfortable with no absolutes

What is vital in running these sessions is offering some sort of conclusion when there is no ‘right’ answer. My third-year cohort knew that a class on ethics was in the schedule – that I was going to get them to answer Menti polls, work in small groups and report back to the room. These are my established teaching styles and by halfway through the semester the students are well used to it. What they weren’t prepared for was that in the end I wasn’t going to tell them a ‘right’ answer.

All the students I have worked on ethics with were somewhat disappointed when in the end they were not offered the ‘right’ answer for the ethical dilemmas posed. What I did do though was still offer them a conclusion to their learning. I point out some of the excellent examples of consideration and thought offered by groups to highlight themes from the four principles. It’s useful here too to point students to where they’ll apply their learning from the session in the short and long term. For my students their future projects all require ethics, inclusion and sustainability statements. It’s important though to also evidence where the learning will go beyond the classroom.

There are examples of cases that in hindsight there are clear cases of ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ (you can pull examples of fields relevant to you, often cited is the Challenger tragedy and Ford Pinto Memo). What we conclude on though is getting comfortable with a lot of decision making professionally being in the ‘middle’ – a complex space with multiple competing factors. Engineers need to work with the principles of ethics to guide us to make sound and well-informed judgements.

It’s essential that tomorrow’s graduate engineers understand that ethics is not a ‘tack on’ statement at the end of a project proposal but rather that ethics is a core part of the role of an engineer. Using the Engineering Ethics Toolkit to help integrate ethics into the core of their education today is a very good way to do that. I recommend the Engineering Ethics Toolkit to all educators – the wealth of the resource cannot be understated in its support to a teacher’s session design and, most importantly, to a student’s learning.

You can find out more about getting involved or contributing to the Engineering Ethics Toolkit here.

This post is also available here.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

Elizabeth Robertson, Teaching Fellow in the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at The University of Strathclyde, discusses how we need to move past our discomfort in order to teach ethics in engineering.

Elizabeth Robertson, Teaching Fellow in the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at The University of Strathclyde, discusses how we need to move past our discomfort in order to teach ethics in engineering.