This month marked a milestone for the engineering education community, as the EPC and E-DAP launched their practical, step-by-step Deaf Awareness Toolkit* to a wider audience for the first time.

This month marked a milestone for the engineering education community, as the EPC and E-DAP launched their practical, step-by-step Deaf Awareness Toolkit* to a wider audience for the first time.

Designed for engineers at all career stages, the toolkit offers practical training to build inclusive skills, implement meaningful measures, and encourage open participation, ultimately improving engineering outcomes through greater accessibility and communication.

Breaking new ground in Engineering inclusion

Hosted by EPC CEO Johnny Rich, the toolkit’s accompanying webinar ‘Being heard: How everyone benefits from deaf awareness’ (available to watch here) brought together over 50 attendees from more than 29 institutions. It marked the first time the UK engineering community has come together in this way to explore how deaf awareness can unlock stronger communication, collaboration and innovation across the sector.

The panel featured voices from RNID, the EPC, E-DAP and professionals with lived experience, offering engineers practical, experience-led guidance grounded in real-world insight—not just theory.

Closed captions: a simple shift, a big impact

One key takeaway is that closed captions do more than support communication. They encourage presenters to structure content more clearly, making complex ideas easier to follow. This is especially important in engineering, where technical information needs to be communicated accurately across classrooms, meetings, and fast paced R&D environments.

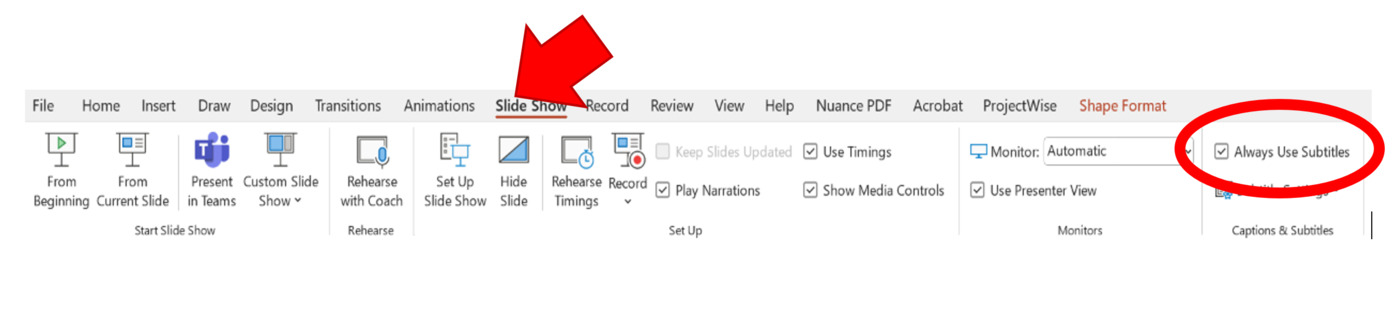

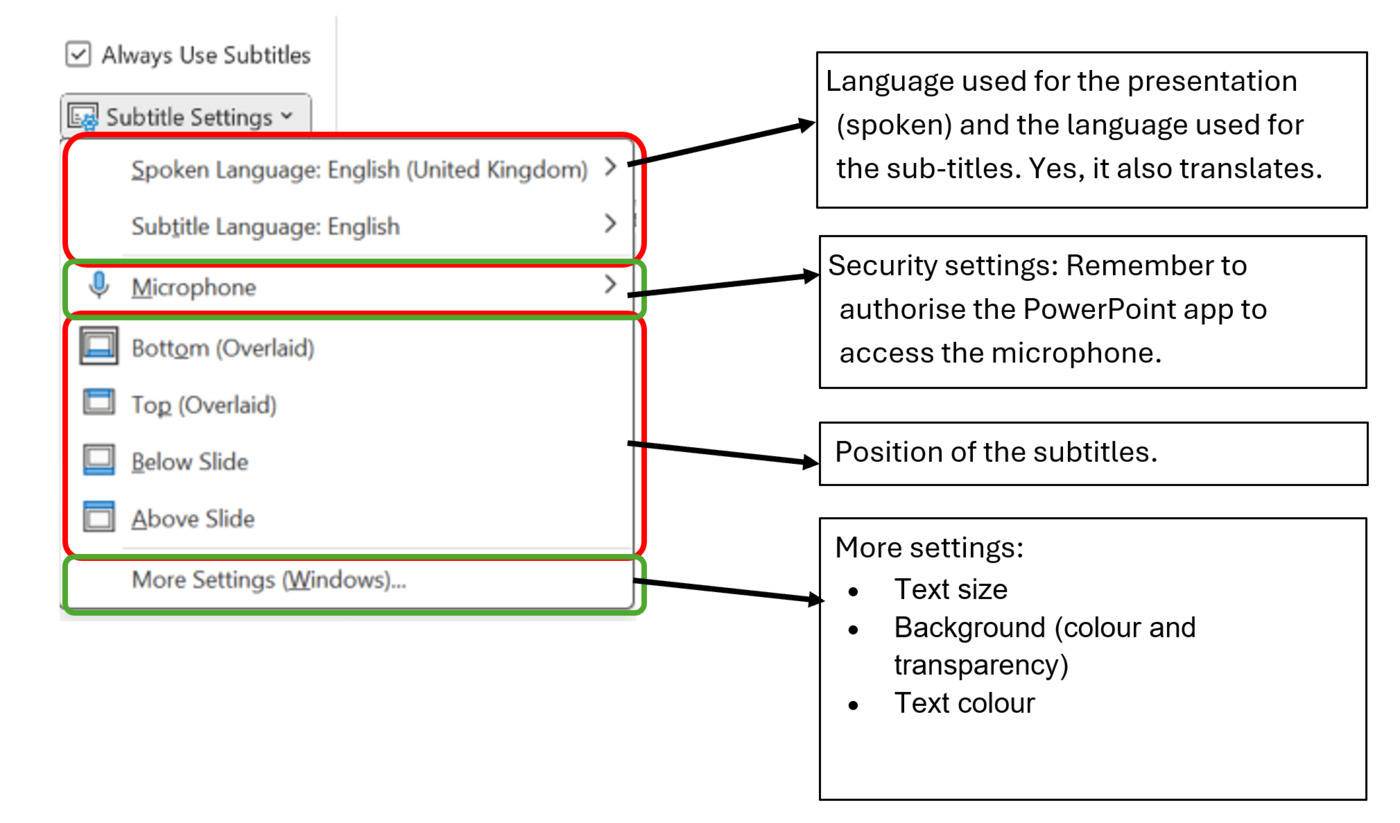

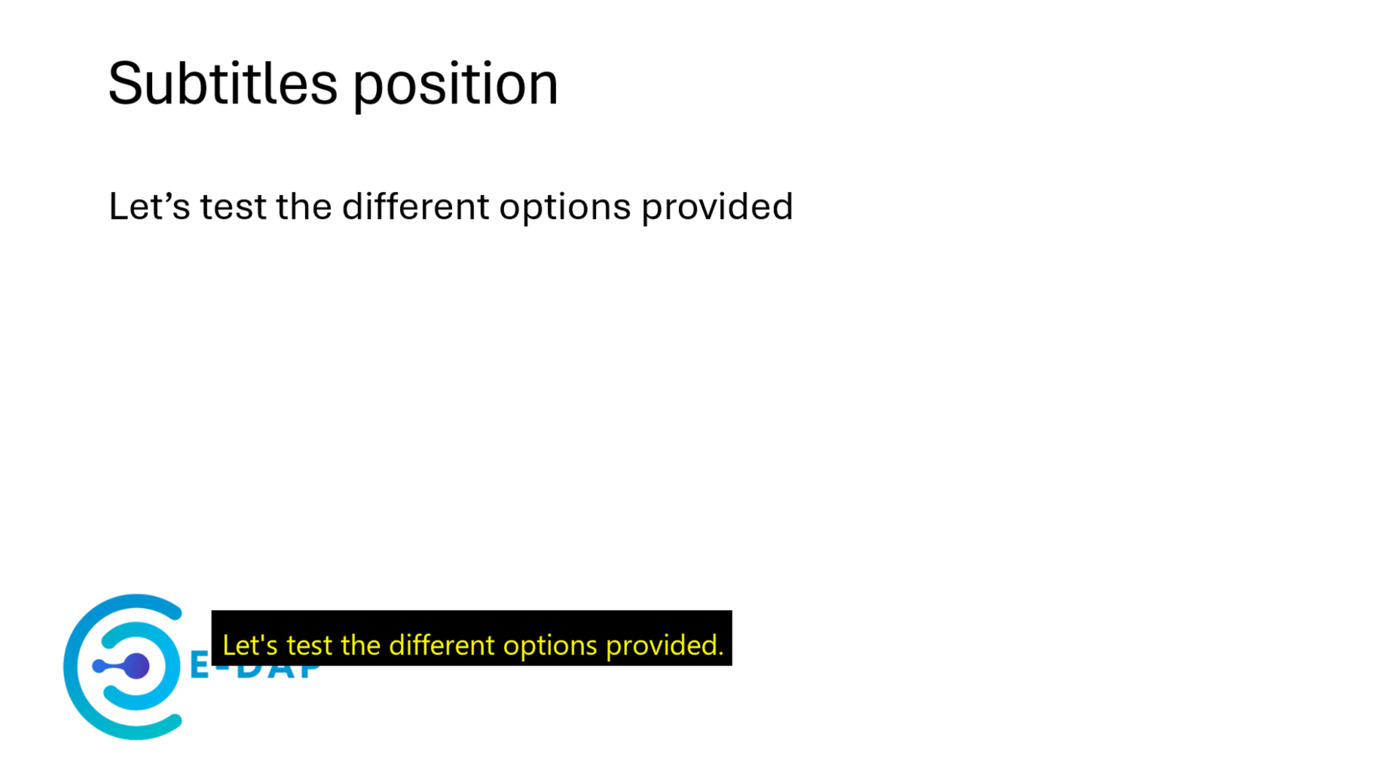

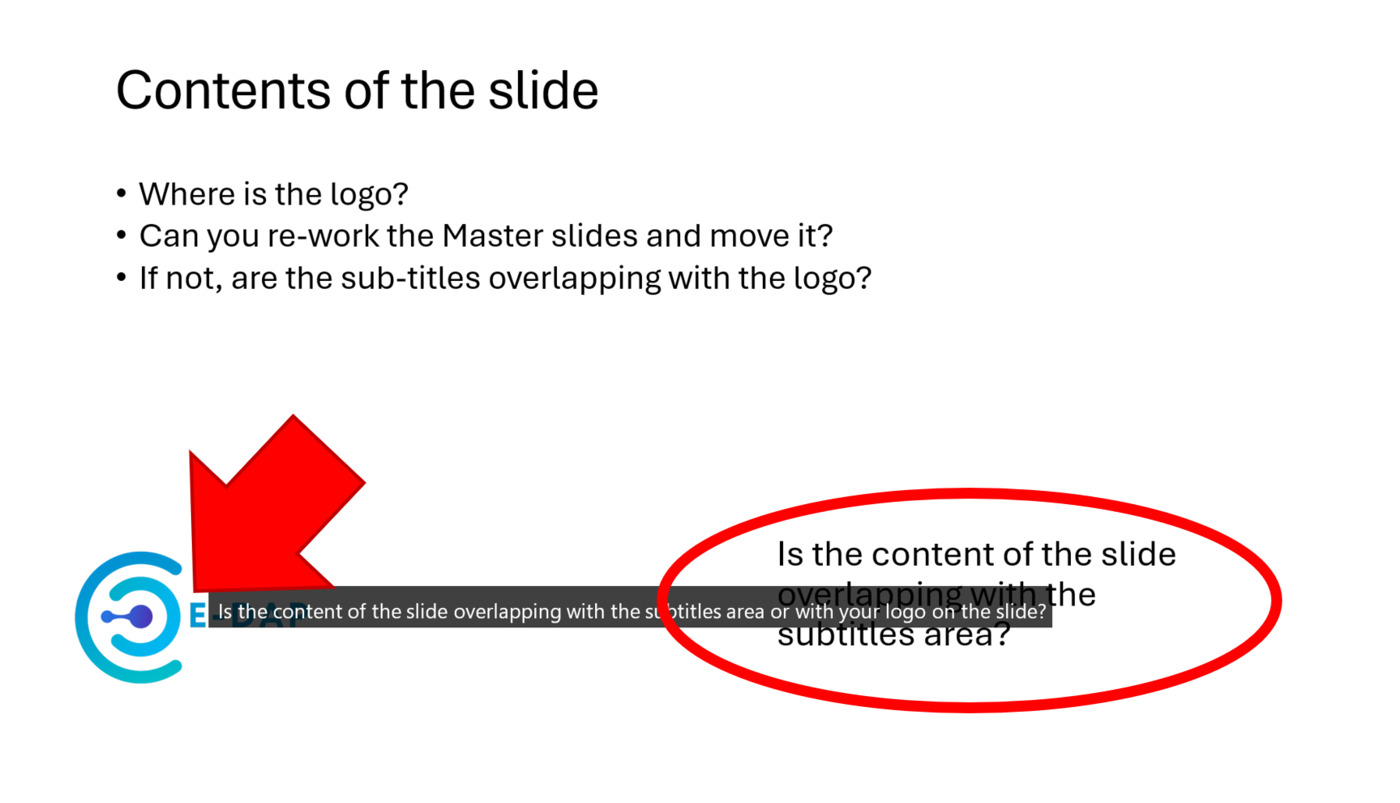

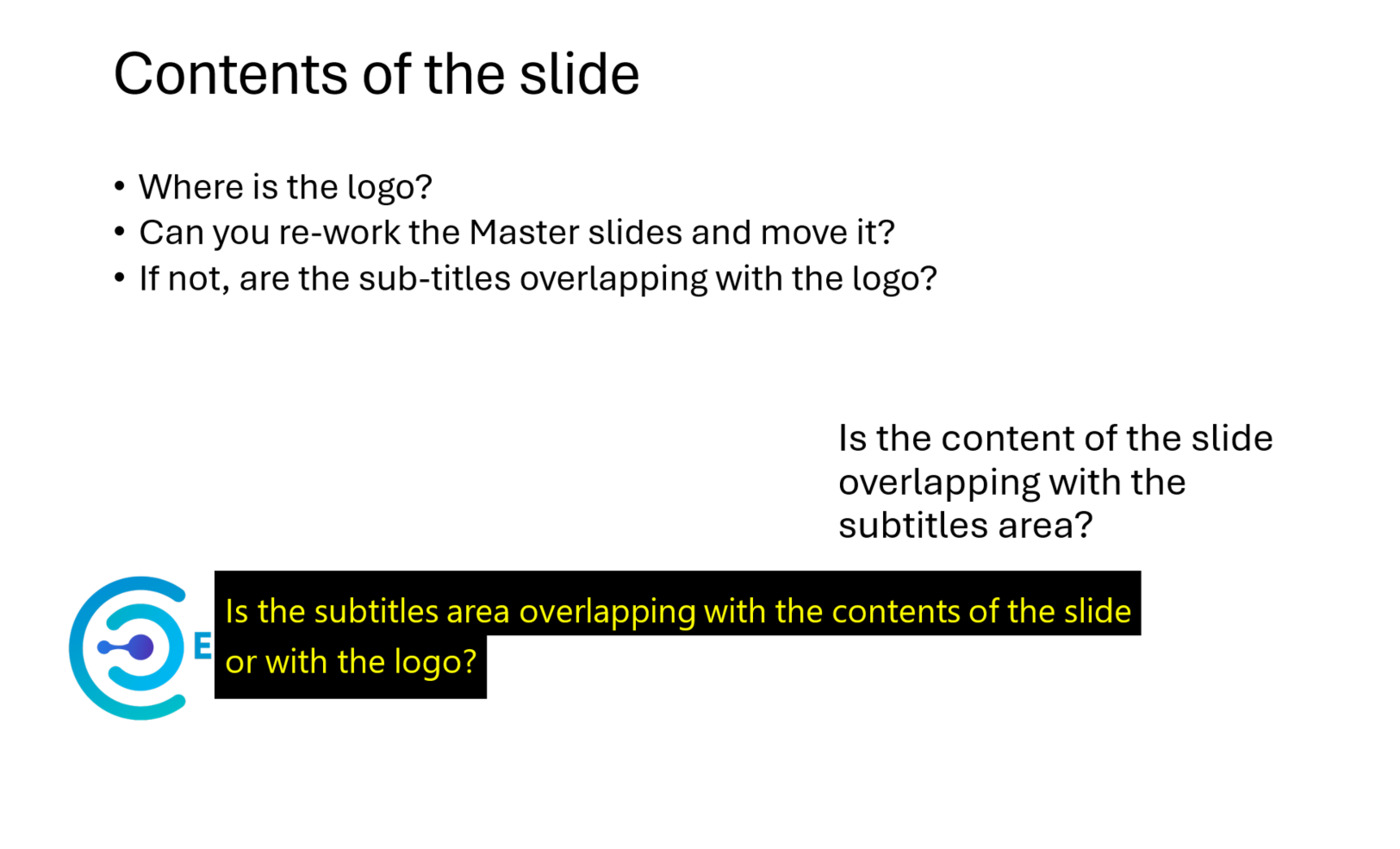

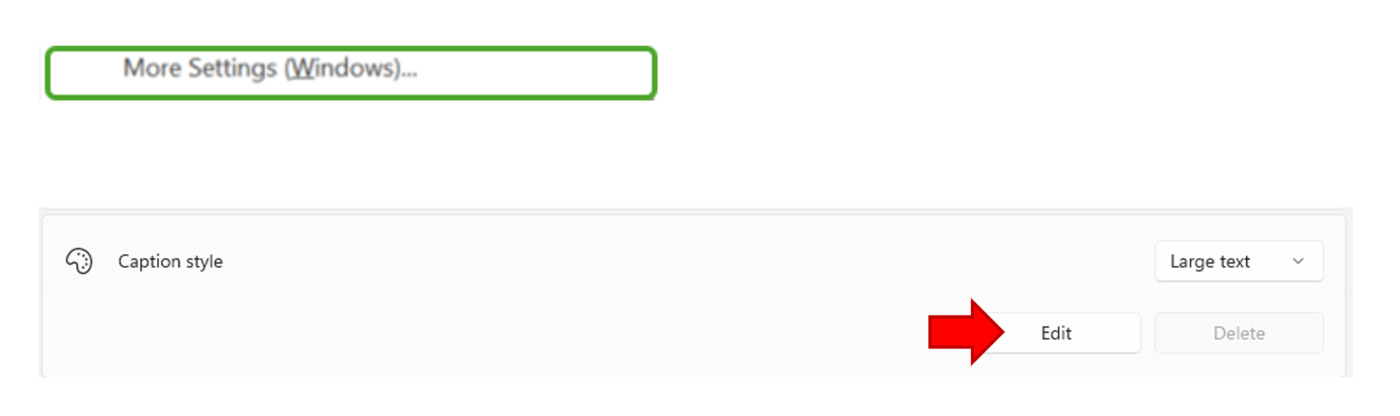

Lucia Capogna (E-DAP) showed just how simple this can be in practice, giving a live demonstration of how to activate captions in PowerPoint. It is a small shift that can make a big difference, and it is easier to implement than many people realise.

Key messages from the panel

Frankie Garforth (RNID)

Frankie addressed widespread misconceptions around deafness, hearing loss and tinnitus, reminding us that over 18 million people in the UK are affected. “You’ll know people living with this,” she said. “It’s good to support them.” She highlighted how deaf-aware technologies like closed captions can significantly improve communication – often in ways people don’t realise until they experience it first hand.

Dr. Sarah Jayne Hitt (EPC)

Sarah Jayne emphasised that some of the most impactful accessibility technologies are already freely available. Many were showcased earlier in the webinar, and others can be explored via the EPC website. These tools, she explained, complement the learning that happens through real human connection – like her own journey learning ASL from a school teacher and later embedding deaf awareness in everyday university life.

Ellie Haywood (E-DAP)

Ellie shared how she took personal responsibility to embed deaf awareness into her workplace a few years ago. Her goal: to make accessibility part of the default way her team operated, so no one would need to ask for special measures. The impact was immediate – improving team efficiency and communication well beyond the deaf community. This inclusive approach proved particularly effective in high-tech R&D projects.

Pilot and student feedback

E-DAP piloted the Deaf Awareness Toolkit with nearly 500 first-year students across civil, mechanical and other engineering disciplines. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, particularly among non-native English speakers, who reported being better able to follow lectures and understand the content.

One simple innovation, using a blank PowerPoint slide during Q&A, made a big difference in helping students catch questions that might otherwise be lost in the noise of a busy classroom.

Survey responses showed nearly two-thirds of students felt neutral to strongly positive about captions and wanted to see them used more widely.

Resources and tools available now

The Deaf Awareness Toolkit is designed to help educators and engineers improve everyday communication and inclusion. It includes:

- An introduction to the Deaf Awareness Project – outlining the aims and origins of the initiative.

- Written guidelines on how to add subtitles in PowerPoint presentations.

- A five-minute walkthrough video demonstrating how to set up captions in PowerPoint.

- Signposting to RNID’s meeting etiquette guidance – practical tips for more inclusive meetings.

- A curated library of links to other deaf awareness resources.

Beyond communication: safety, inclusion and culture

Deaf awareness goes beyond communication. In engineering environments, visual alarms and clear auditory cues support safety. Inclusive meeting behaviours, accessible research environments, and awareness of hearing health can all contribute to a more inclusive and effective working culture. Clear communication isn’t just a benefit for deaf individuals, it supports better outcomes for everyone.

The vision: One Million Engineers

This is just the beginning. Our goal is to engage one million engineers with accessibility.

With the EPC platform reaching 7,500 engineering academics across 82 institutions, and 179,000 students enrolled in those institutions, we are taking our first steps towards that vision.

Accessibility isn’t an optional extra. It’s a core part of engineering education and inclusion that we want to instil in future engineers.

What’s next

E-DAP and the EPC are now working together to embed deaf awareness more deeply into engineering practice and culture. Future activities will include:

- Awareness campaigns across the engineering sector.

- Continued toolkit development and events focused on neurodiversity, ethics and inclusion.

- Action-based inspiration from initiatives like our visit to Google’s Accessibility Discovery Centre.

*E-DAP’s Role as an Ally

E-DAP is an active ally to the Deaf and deaf communities. We do not speak for them, but work in partnership with experts, advocates, and individuals with lived experience to improve awareness and inclusion in engineering and education.

We collaborate with the community to learn and co-create. Our goal is to support engineering innovation by enabling better communication for everyone, and to implement inclusion in engineering through technology, tools, learning, and partnerships that embed inclusive practices and create lasting change.

A Note on Language

Language matters. Whether someone identifies as Deaf, deaf, has hearing loss or tinnitus, they are all individuals, and respectful language helps create more inclusive spaces. If you’re unsure how to phrase something, ask. It’s always better to check than assume. Helpful guidance on terminology is available from the RNID.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.