Author: Dr. Jemma L. Rowlandson (University of Bristol).

Topic: Achieving carbon-neutral aviation by 2050.

Tool type: Teaching.

Relevant disciplines: Chemical; Aerospace; Mechanical; Environmental; Energy.

Keywords: Design and innovation; Conflicts of interest; Ethics; Regulatory compliance; Stakeholder engagement; Environmental impact; AHEP; Sustainability; Higher education; Pedagogy; Assessment.

AHEP mapping: This resource addresses two of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): The Engineer and Society (acknowledging that engineering activity can have a significant societal impact) and Engineering Practice (the practical application of engineering concepts, tools and professional skills). To map this resource to AHEP outcomes specific to a programme under these themes, access AHEP 4 here and navigate to pages 30-31 and 35-37.

Related SDGs: SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy); SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure); SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production); SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Educational aim: Apply interdisciplinary engineering knowledge to a real-world sustainability challenge in aviation, foster ethical reasoning and decision-making with regards to environmental impact, and develop abilities to collaborate and communicate with a diverse range of stakeholders.

Educational level: Intermediate.

Learning and teaching notes:

This case study provides students an opportunity to explore the role of hydrogen fuel in the aviation industry. Considerable investments have been made in researching and developing hydrogen as a potential clean and sustainable energy source, particularly for hydrogen-powered aircraft. Despite the potential for hydrogen to be a green and clean fuel there are lingering questions over the long-term sustainability of hydrogen and whether technological advancements can progress rapidly enough to significantly reduce global carbon dioxide emissions. The debate around this issue is rich with diverse perspectives and a variety of interests to consider. Through this case study, students will apply their engineering expertise to navigate this complex problem and examine the competing interests involved.

This case is presented in parts, each focusing on a different sustainability issue, and with most parts incorporating technical content. Parts may be used in isolation, or may be used to build up the complexity of the case throughout a series of lessons.

Learners have the opportunity to:

- Understand the principles of hydrogen production, storage, and emissions in the context of aviation.

- Assess the environmental, economic, and social impacts of adopting hydrogen technology in the aviation industry.

- Develop skills in making estimates and assumptions in real-world engineering scenarios.

- Explore the ethical dimensions of engineering decisions, particularly concerning sustainability and resource management.

- Examine the influence of policy and stakeholder perspectives on the adoption of green hydrogen within the aviation industry.

Teachers have the opportunity to:

- Integrate concepts related to renewable energy sources, with a focus on hydrogen.

- Discuss the engineering challenges and solutions in storing and utilising hydrogen in aviation.

- Foster critical thinking about the balance between technological innovation, environmental sustainability, and societal impact.

- Guide students in understanding the role of policy in shaping technological advancements and environmental strategies.

- Assess students’ ability to apply engineering principles to solve complex, open-ended, real-world problems.

Supporting resources:

Learning and teaching resources:

Hydrogen fundamentals resources:

- Case Study Workbook – designed for this study to give a broad overview of hydrogen, based primarily on the content below from US DoE.

- US DoE – College of the Desert and Sunlight Transport – Hydrogen basics are covered in Module 1, 2 and 3.

- Hydrogen Aware – Set of modules for a more comprehensive background to hydrogen with a UK-specific context.

We recommend encouraging the use of sources from a variety of stakeholders. Encourage students to find their own, but some examples are included below:

- FlyZero Open Source Reports Archive: A variety of technical reports focused on hydrogen in aviation specifically including concept aircraft, potential life cycle emissions, storage, and usage.

- Hydrogen in Aviation Alliance: Press release (September 2023) announcing an agreement amongst some of the major players in aviation to focus on hydrogen.

- Lee et al. (2018) The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018: Open manuscript available. This seminal paper examines the contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate change.

- Safe Landing: A group of aviation workers campaigning for long-term employment. Projected airline growth is not compatible with net zero goals and the current technology is not ready for decarbonisation, action is drastically needed now to safeguard the aviation industry and prevent dangerous levels of warming.

- UK Government Hydrogen Strategy: Sets out the UK government view of how to develop a low carbon hydrogen sector including aviation projects including considerations of how to create a market.

Pre-Session Work:

Students should be provided with an overview of the properties of hydrogen gas and the principles underlying the hydrogen economy: production, storage and transmission, and application. There are several free and available sources for this purpose (refer to the Hydrogen Fundamentals Resources above).

Introduction

“At Airbus, we believe hydrogen is one of the most promising decarbonisation technologies for aviation. This is why we consider hydrogen to be an important technology pathway to achieve our ambition of bringing a low-carbon commercial aircraft to market by 2035.” – Airbus, 2024

As indicated in the industry quote above, hydrogen is a growing area of research interest for aviation companies to decarbonise their fleet. In this case study, you are put in the role of working as an engineering consultant and your customer is a multinational aerospace corporation. They are keen to meet their government issued targets of reducing carbon emissions to reach net zero by 2050 and your consultancy team has been tasked with assessing the feasibility of powering a zero-emission aircraft using hydrogen. The key areas your customer is interested in are:

- The feasibility of using green hydrogen as a fuel for zero-emission aviation;

- The feasibility of storing hydrogen in a confined space like an aircraft;

- Conducting a stakeholder analysis on the environmental impact of using hydrogen for aviation.

Part one: The aviation landscape

Air travel connects the world, enabling affordable and reliable mass transportation between continents. Despite massive advances in technology and infrastructure to produce more efficient aircraft and reduce passenger fuel consumption, carbon emissions have doubled since 2019 and are equivalent to 2.5 % of global CO2 emissions.

- Activity: Discuss what renewable energy sources are you aware of that could be used for zero-emission aviation?

Your customer is interested in the feasibility of hydrogen for aviation fuel. However, there is a debate within the management team over the sustainability of hydrogen. As the lead engineering consultant, you must guide your customer in making an ethical and sustainable decision.

Hydrogen is a potential energy carrier which has a high energy content, making it a promising fuel for aviation. Green hydrogen is produced from water and is therefore potentially very clean. However, globally most hydrogen is currently made from fossil fuels with an associated carbon footprint. Naturally occurring as a gas, the low volumetric density makes it difficult to transport and add complications with storage and transportation.

- Activity: From your understanding of hydrogen, what properties make it a promising fuel for aircraft? And what properties make it challenging?

- Optional activity: Recap the key properties of hydrogen – particularly the low gas density and low boiling point which affect storage.

Part two: Hydrogen production

Hydrogen is naturally abundant but is often found combined with other elements in various forms such as hydrocarbons like methane (CH4) and water (H2O). Methods have been developed to extract hydrogen from these compounds. It is important to remember that hydrogen is an energy carrier and not an energy source; it must be generated from other primary energy sources (such as wind and solar) converting and storing energy in the form of hydrogen.

- Research: What production methods of hydrogen are you aware of? Where does most of the world’s hydrogen come from currently?

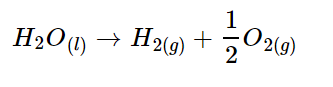

The ideal scenario is to produce green hydrogen via electrolysis where water (H2O) is split using electricity into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2). This makes green hydrogen potentially completely green and clean if the process uses electricity from renewable sources. The overall chemical reaction is shown below:

However, the use of water—a critical resource—as a feedstock for green hydrogen, especially in aviation, raises significant ethical concerns. Your customer’s management team is divided on the potential impact of this practice on global water scarcity, which has been exacerbated by climate change. You have been tasked with assessing the feasibility of using green hydrogen in aviation for your client. Your customer has chosen their London to New York route (3,500 nmi), one of their most popular, as a test-case.

- Activity: Estimate how much water a hydrogen plane would require for a journey of 3500 nmi (London to New York). Can you validate your findings with any external sources? Hint: How much water does it take to produce 1 kg of green hydrogen? Consider the chemical equation above.

- Activity: Consider scaling this up and estimate how much water the entire UK aviation fleet would require in one year. Compare your value to the annual UK water consumption, would it be feasible to use this amount of water for aviation?

- Discussion: From your calculations and findings so far, discuss the practicality of using water for aviation fuel. Consider both the obstacles and opportunities involved in integrating green hydrogen in aviation and the specific challenges the aviation industry might face.

Despite its potential for green production, globally the majority of hydrogen is currently produced from fossil fuels – termed grey hydrogen. One of your team members has proposed using grey hydrogen as an interim solution to bridge the transition to green hydrogen, in order for the company to start developing the required hydrogen-related infrastructure at airports. They argue that carbon capture and storage technology could be used to reduce carbon emissions from grey hydrogen while still achieving the goal of decarbonisation. Hydrogen from fossil fuels with an additional carbon capture step is known as blue hydrogen.

However, this suggestion has sparked a heated debate within the management team. While acknowledging the potential to address the immediate concerns of generating enough hydrogen to establish the necessary infrastructure and procedures, many team members argued that it would be a contradictory approach. They highlighted the inherent contradiction of utilising fossil fuels, the primary driver of climate change, to achieve decarbonisation. They emphasised the importance of remaining consistent with the ultimate goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels altogether and reducing overall carbon emissions. Your expertise is now sought to weigh these options and advise the board on the best course of action.

- Optional activity: Research the argument for and against using grey or blue hydrogen as an initial step in developing hydrogen infrastructure and procedures, as a means to eventually transition to green hydrogen. Contrast this with the strategy of directly implementing green hydrogen from the beginning. Split students into groups to address both sides of this debate.

- Discussion: Deliberate on the merits and drawbacks of using grey or blue hydrogen to catalyse development of hydrogen aviation infrastructure. What would you recommend—prioritising green hydrogen development or starting with grey or blue hydrogen as a transitional step? How will you depict or visualise your recommendation to your client?

Part three: Hydrogen storage

Despite an impressive gravimetric energy density (the energy stored per unit mass of fuel) hydrogen has the lowest gas density and the second-lowest boiling point of all known chemical fuels. These unique properties pose challenges for storage and transportation, particularly in the constrained spaces of an aircraft.

- Activity: Familiarise yourself with hydrogen storage methods. What hydrogen storage methods are you aware of? Thinking about an aviation context what would their advantages and disadvantages be?

As the lead engineering consultant, you have been tasked with providing expert advice on viable hydrogen storage options for aviation. Your customer has again chosen their London to New York route (3,500 nmi) as a test-case because it is one of their most popular, transatlantic routes. They want to know if hydrogen storage can be effectively managed for this route as it could set a precedent for wider adoption for their other long-haul flights. The plane journey from London to New York is estimated to require around 15,000 kg of hydrogen (or use the quantity estimated previously estimated in Part 2 – see Appendix for example).

- Activity: Estimate the volume required to store the 15,000 kg of hydrogen as a compressed gas and as a liquid.

- Discussion: How feasible are compressed gas and liquid hydrogen storage solutions? The space taken up by the fuel is one consideration but what other aspects are important to consider? How does this compare to the current storage solution for planes which use conventional jet fuel. Examples of topics to consider are: materials required for storage tanks, energy required to liquify or compress the hydrogen, practicality of hydrogen storage and transport to airports, location and distance between hydrogen generation and storage facilities, considerations of fuel leakage. When discussing encourage students to compare to the current state of the art, which is jet fuel.

Part four: Emissions and environmental impact

In Part four, we delve deeper into the environmental implications of using hydrogen as a fuel in aviation with a focus on emissions and their impacts across the lifecycle of a hydrogen plane. Aircraft can be powered using either direct combustion of hydrogen in gas turbines or by reacting hydrogen in a fuel cell to produce electricity that drives a propeller. As the lead engineering consultant, your customer has asked you to choose between hydrogen combustion in gas turbines or the reaction of hydrogen in fuel cells. The management team is divided on the environmental impacts of both methods, with some emphasising the technological readiness and efficiency of combustion and others advocating for the cleaner process of fuel cell reaction.

- Activity: Research the main emissions associated with combustion of hydrogen and electrochemical reaction of hydrogen in fuel cells. Compare to the emissions associated with combustion of standard jet fuel. Students should consider not only CO2 emissions but also other pollutants such as NOx, SOx, and particulate matter.

- Discussion: What are the implications of these emissions on air quality and climate change. Discuss the trade-offs between the different methods of utilising hydrogen in terms of the environmental impact. Compare to the current standard of jet fuel combustion.

Both combustion of hydrogen in an engine and reaction of hydrogen in a fuel cell will produce water as a by-product. The management team are concerned over the effect of using hydrogen on the formation of contrails. Contrails are clouds of water vapour produced by aircraft that have a potential contribution to global warming but the extent of their impact is uncertain.

- Activity: Investigate how combustion (of both jet fuel and hydrogen) and fuel cell reactions contribute to contrail formation. What is the potential climactic effect of contrails?

- Optional extension: How can manufacturers and airlines act to reduce water emissions and contrail formation – both for standard combustion of jet fuel and future hydrogen solutions?

- Discussion: Based on your findings, which hydrogen propulsion technology would you recommend to the management team?

So far we have considered each aspect of the hydrogen debate in isolation. However, it is important to consider the overall environmental impact of these stages as a whole. Choices made at each stage of the hydrogen cycle – generation, storage, usage – will collectively impact the overall environmental impact and sustainability of using hydrogen as an aviation fuel and demonstrates how interconnected our decisions can be.

- Activity: Assign students to groups based on the stage of a hydrogen lifecycle (generation, storage/transport, usage). Each group could research and discuss the potential emissions and environmental impacts associated with their assigned stage. Consider both direct and indirect emissions, like energy used in production processes or emissions related to infrastructure development. Principles such as life cycle assessment can be incorporated for a holistic view of hydrogen emissions.

- Activity: After the individual group discussions, each group could present their findings and perspectives on their stage of the lifecycle. The whole class could then reflect on the overall environmental impacts of hydrogen in aviation. How do these impacts compare across different stages of the lifecycle? What are the trade-offs involved in choosing different types of hydrogen (green, blue, grey) and storage/transportation solutions?

- Discussion: Conclude with a reflective discussion. Students bring together their findings on the life cycle stages of hydrogen and present their overall perspectives on the environmental sustainability of using hydrogen in aviation.

Part five: Hydrogen aviation stakeholders

Hydrogen aviation is an area with multiple stakeholders with conflicting priorities. Understanding the perspectives of these key players is important when considering the feasibility of hydrogen in the aviation sector.

- Activity: Who are the key players in this scenario? What are their positions and perspectives? How can you use these perspectives to understand the complexities of the situation more fully?

Your consultancy firm is hosting a debate for the aviation industry in order to help them make a decision around hydrogen-based technologies. You have invited representatives from consumer groups, the UK government, Environmental NGOs, airlines, and aircraft manufacturers.

- Activity: Take on the role of these key stakeholders, ensuring you understand their perspective and priorities. This could form part of a separate research exercise, or students can use the key points given below. Debate whether or not hydrogen fuel should be used to help the aviation sector reach net zero.

| Stakeholder | Key priorities and considerations |

| Airline & Aerospace Manufacturer |

|

| UK Government |

|

| Environmental NGOs |

|

| Consumer |

|

Appendix: Example calculations

There are multiple methods for approaching these calculations. The steps shown below are just one example for illustrative purposes.

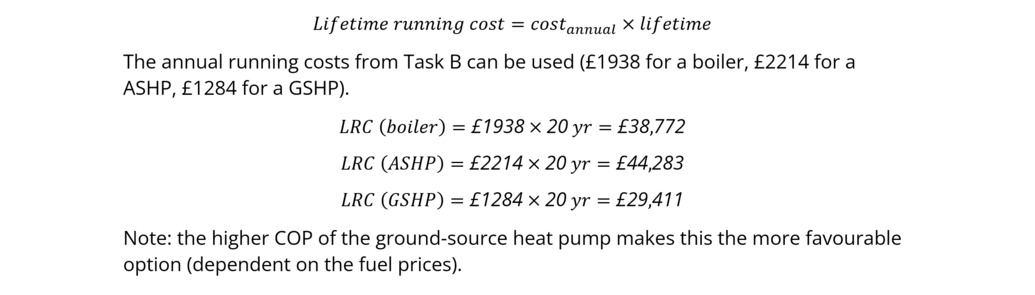

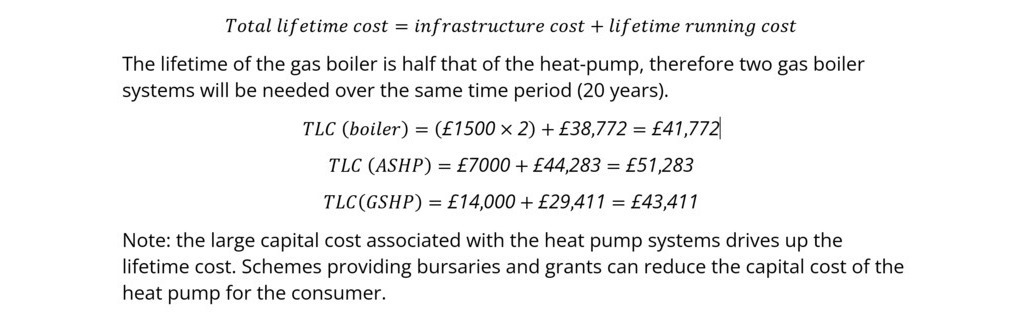

Part two: Hydrogen production

Challenge: Estimate the volume of water required for a hydrogen-powered aircraft.

Assumptions around the hydrogen production process, aircraft, and fuel requirement can be given to students or researched as a separate task. In this example we assume:

- All hydrogen is generated via electrolysis of fresh water with an efficiency of 100%.

- A mid-size aircraft required with ~300 passenger capacity and flight range of ~3500 nmi (London to New York).

- Flight energy requirement for a kerosene-fuelled jet is the same as a hydrogen-fuelled jet.

Example estimation:

1. Estimate the energy requirement for a mid-size jet

No current hydrogen-fuelled aircraft exists, so we can use a kerosene-fuelled analogue. Existing aircraft that meet the requirements include the Boeing 767 or 747. The energy requirement is then:

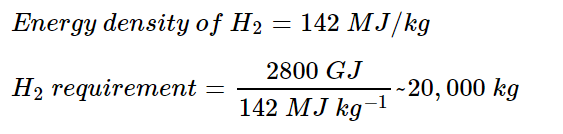

2. Estimate the hydrogen requirement

Assuming a hydrogen plane has the same fuel requirement:

3. Estimate the volume of water required

Assuming all hydrogen is produced from the electrolysis of water:

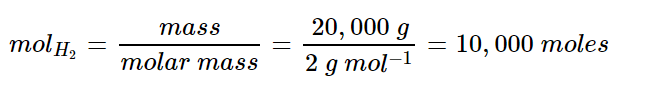

For this reaction, we know one mole of water produces one mole of hydrogen. We need to calculate the moles for 20,000 kg of hydrogen:

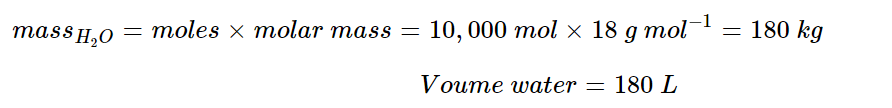

With a 1:1 molar ratio, we can then calculate the mass of water:

This assumes an electrolyser efficiency of 100%. Typical efficiency values are under 80%, which would yield:

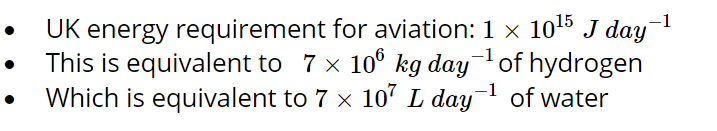

Challenge: Is it feasible to power the UK aviation fleet with water?

The total energy requirement for UK aviation can be given to students or set as a research task.

Estimation can follow a similar procedure to the above.

Multiple methods for validating and assessing the feasibility of this quantity of water. For example, the UK daily water consumption is 14 billion litres. The water requirement estimated above is < 1 % of this total daily water consumption, a finding supported by FlyZero.

Part three: Hydrogen storage

Challenge: Is it feasible to store 20,000 kg of hydrogen in an aircraft?

There are multiple methods of determining the feasibility of storage volume. As example is given below.

1. Determining the storage volume

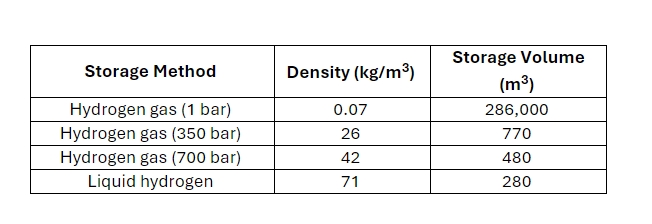

The storage volume is dependent on the storage method used. Density values associated with different storage techniques can be research or given to students (included in Table 2). The storage volume required can be calculated from the mass of hydrogen and density of storage method, example in Table 2.

Table 2: Energy densities of various hydrogen storage methods

2. Determining available aircraft volume

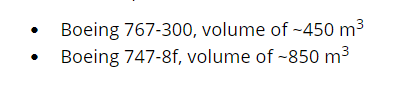

A straightforward method is to compare the available volume on an aircraft with the hydrogen storage volume required. Aircraft volumes can be given or researched by students. Examples:

This assumes hydrogen tanks are integrated into an existing aircraft design. Liquid hydrogen can feasibly fit into an existing design, though actual volume will be larger due to space/constraint requirements and additional infrastructure (pipes, fittings, etc) for the tanks. Tank size can be compared to conventional kerosene tanks and a discussion encouraged over where in the plane hydrogen tanks would need to be (conventional liquid fuel storage is in the wings of aircraft, this is not possible for liquid storage tanks due to their shape and infrastructure storage is inside the fuselage). Another straightforward method for storage feasibility is modelling the hydrogen volume as a simple cylinder and comparing to the dimensions of a suitable aircraft.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.

To view a plain text version of this resource, click here to download the PDF.

Author: Dr Irene Josa (University College London). The author would like to acknowledge Colin Church (IOM3) who provided valuable feedback during the development of this case.

Author: Dr Irene Josa (University College London). The author would like to acknowledge Colin Church (IOM3) who provided valuable feedback during the development of this case.