Toolkit: Complex Systems Toolkit.

Toolkit: Complex Systems Toolkit.

Topic: Developing competence in model-based systems engineering.

Title: Practical control engineering education through the ACE-Model.

Resource type: Teaching activity.

Relevant disciplines: Systems engineering; electrical engineering; control engineering.

Keywords: Available soon.

Licensing: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Downloads: A PDF of this resource will be available soon.

Learning and teaching resources:

Related INCOSE Competencies: Toolkit resources are designed to be applicable to any engineering discipline, but educators might find it useful to understand their alignment to competencies outlined by the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). The INCOSE Competency Framework provides a set of 37 competencies for Systems Engineering within a tailorable framework that provides guidance for practitioners and stakeholders to identify knowledge, skills, abilities and behaviours crucial to Systems Engineering effectiveness. A free spreadsheet version of the framework can be downloaded.

This resource relates to the Systems Thinking, Systems Modelling and Analysis, Integration, and Technical Leadership INCOSE competencies.

AHEP4 mapping: This resource addresses several of the themes from the UK’s Accreditation of Higher Education Programmes fourth edition (AHEP4): Analytical Tools and Techniques (critical to the ability to model and solve problems), and Integrated / Systems Approach (essential to the solution of broadly-defined problems).

Educational level: Beginner; intermediate.

Learning and teaching notes:

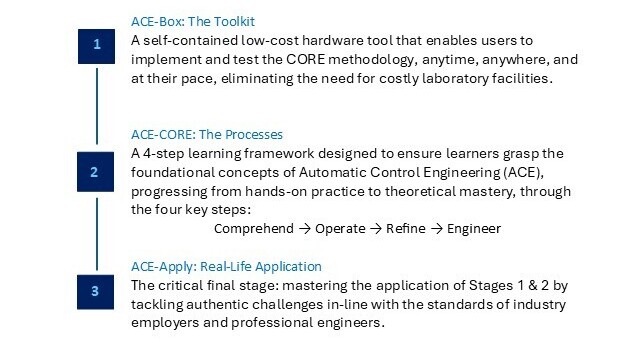

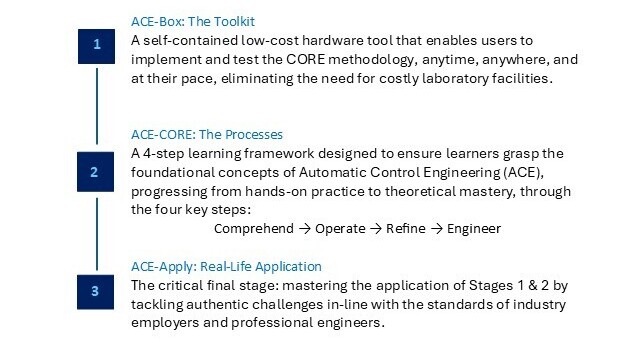

Modern engineering is increasingly digital, interconnected, and system oriented. To prepare students for this evolving landscape, the Automatic Control Engineering (ACE) Model offers a systems-driven, application-focused framework for practical control engineering education. Developed through a MathWorks-funded project launched in the summer of 2025, the ACE-Model unifies three complementary components that together cultivate systems thinking and model-based systems engineering competence:

- ACE-Box: The Toolkit

- ACE-CORE: The Processes

- ACE-Apply: Real-World Application

Learners have the opportunity to:

- Engage with the entire ACE-CORE (Comprehend – Operate – Refine – Engineer) framework.

- Experience a welcoming and accessible introduction to ACE, without an early overemphasis on mathematics. This stands in contrast to the traditional approach, where topics such as Laplace transforms are introduced early on, often creating unnecessary barriers to engagement (Abou-Hayt and Dahl, 2023).

- Develop systems awareness and motivation.

- Develop confidence, engagement, and curiosity.

- Gain the technical knowledge and systems integration mindset required to thrive in the complex, adaptive landscape of digital engineering.

Teachers have the opportunity to:

- Introduce control theory topics in a way that addresses the concern of students finding it difficult to link abstract control theory with the world of control engineering practice (Rossiter, 2022; Badau, et al., 2024).

- Introduce industry-standard systems processes such as the V-diagram and model-based design workflows.

- Progressively link theory to practice.

- Support AHEP4 expectations for developing graduates who can apply integrated systems approaches to solving complex problems and the INCOSE Systems Engineering Competency areas of systems thinking, integration, and technical leadership.

What does the ACE-Model consist of?:

Figure 1: The ACE-Model: Integrating the Toolkit (ACE-Box), with the Processes (ACE-CORE), to Lead to the Real-Life Application (ACE-Apply) to build a progressive mastery in Automatic Control Engineering (ACE).

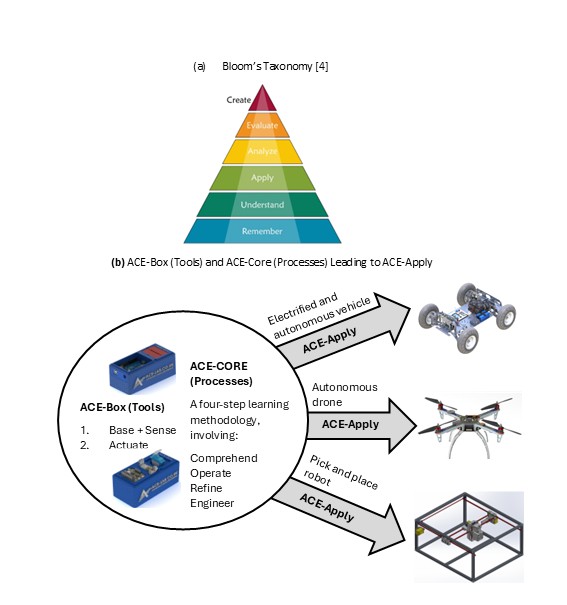

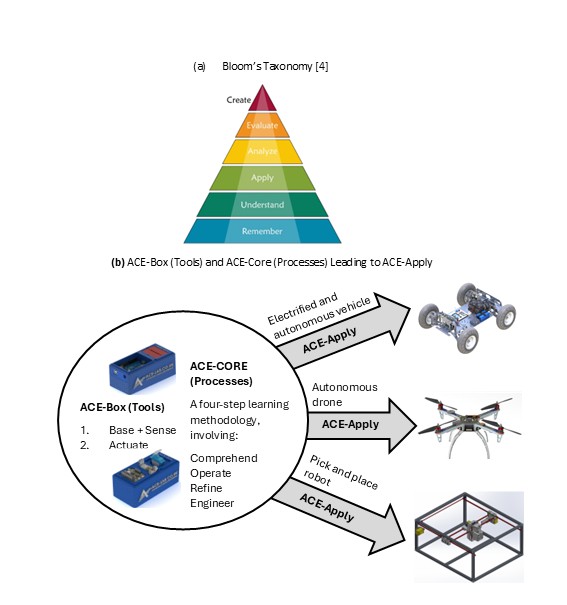

The ACE-Model is closely aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy, see (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) and Figure 2(a) providing a structured pathway for students to progress through the cognitive hierarchy, while developing capabilities across multiple levels of system abstraction. Figure 2(b) offers a schematic view of the three stages of the ACE-Model, as introduced in Figure 1. An initial overview of the ACE-Model is presented here, with further details provided in the following sections.

The ACE-Box is a portable, self-contained hardware tool that brings ACE to life beyond the traditional costly, full-scale laboratories. All that is required is a laptop and the ACE-Box. Designed to support the ACE-CORE methodology, ACE-Box can be set up on a desk, in a classroom, or even at home. MATLAB and Simulink serve as the primary platforms for model-based design, enabling system modelling, control system development, and the deployment of control algorithms to physical hardware (e.g. Arduino Uno) through code generation tools.

ACE-CORE guides learners through successive levels of Bloom’s framework:

- Comprehend aligns with Remember and Understand on the Bloom Taxonomy, enabling students to grasp the applications of control engineering before advancing.

- Operate corresponds to Apply on the Bloom Taxonomy, as students engage directly with control systems, supported by Stage 2, making use of the ACE-Box (hardware or virtual).

- Refine maps to both Analyse and Evaluate on the Bloom Taxonomy, where learners diagnose performance, compare outcomes, and adapt solutions to meet stakeholder requirements.

- Engineer extends this process to system-level design and synthesis, making use of modelling and simulation tools such as MATLAB and Simulink. At this stage, students revisit the full cycle (Remember through to Evaluate), but at a higher level of integration with the use of control theory, again supported by the ACE-Box.

At each stage of CORE, learners move from recognising system components to synthesising complex interactions, mirroring the systems engineering lifecycle from requirement capture through verification and validation. This alignment supports AHEP4’s emphasis on analytical and problem-solving competence and INCOSE’s System Definition and Integration competencies.

Finally, learners progress to Create, the highest stage of Bloom’s Taxonomy, by applying their knowledge to design complete control systems for real-world applications such as drones, vehicles, and automation systems. In this way, the ACE-Model scaffolds learning in parallel with Bloom’s progression, from foundational comprehension to advanced problem-solving, design and innovation.

Together, these three pillars form a cohesive learning ecosystem: the toolkit, the process, and the application.

Figure 2: Bloom’s Taxonomy (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) (a) and the ACE-Model Three Stages (b).

Collaborative community:

The ACE-Model ‘sits’ within the ACE-Lab, a collaborative community of academics and industry professionals committed to developing, validating, and disseminating open-access systems education resources. The ACE-Lab approach embodies complex adaptive systems principles, where the community evolves through continuous feedback, iteration, and co-design. Membership to the ACE-Lab is open to anyone who shares our vision of advancing control engineering teaching tools and practices. Through this approach, the ACE-Model equips graduates with the knowledge and hands-on skills required to excel in modern ACE careers. Find out more about the ACE-Lab through the following website: www.ace-lab.co.uk

As an evolving community, ACE-Lab continually expands its open-access content through the active contributions of its members. New materials are regularly developed and shared, ensuring the resources remain current and relevant. Through this dynamic, collaborative approach, embodied in the ACE-Model, students not only gain technical knowledge but also develop the capacity to understand, navigate, and work effectively with complex, interconnected engineering systems.

ACE-Box: The toolkit:

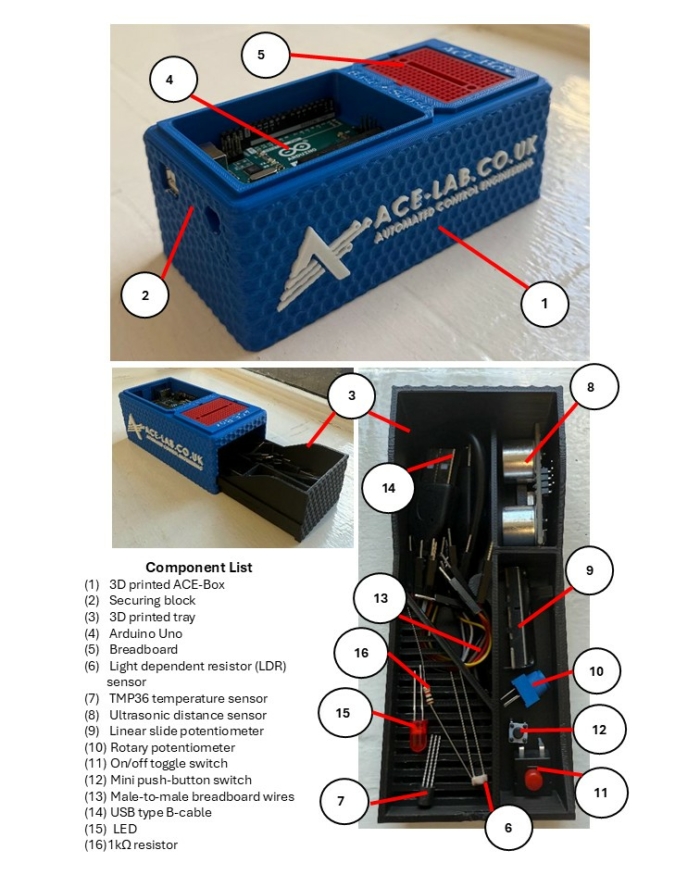

The ACE-Box is based on the early development work of Control-Lab-in-a-Box (Pickering, 2023; 2025). CLB integrates sensors, actuators, and microcontroller to allow students to experience dynamic behaviour, and feedback control.

For now, two ACE-Box kits have been developed:

1. Base and sense

2. Actuate

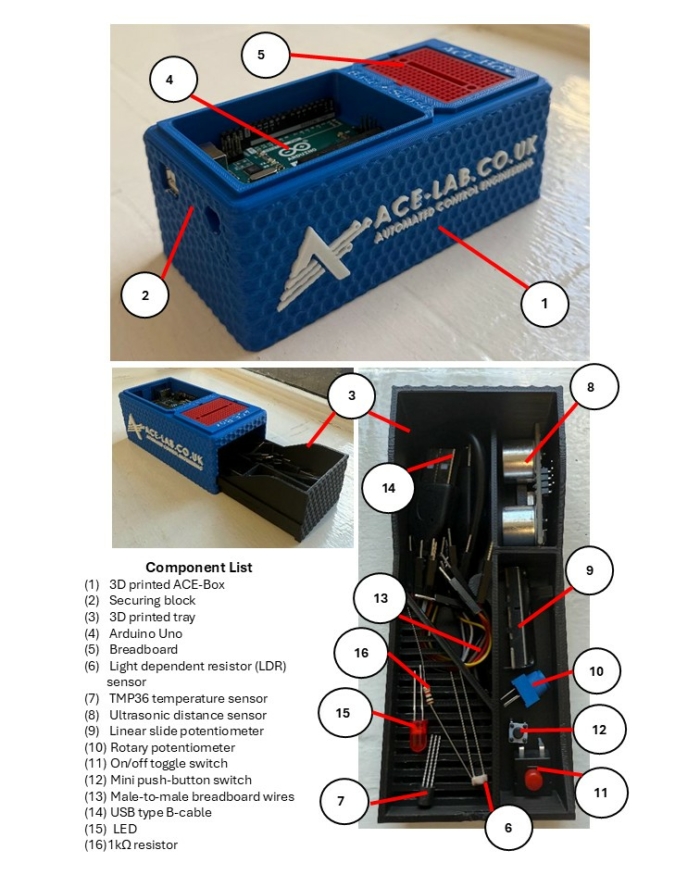

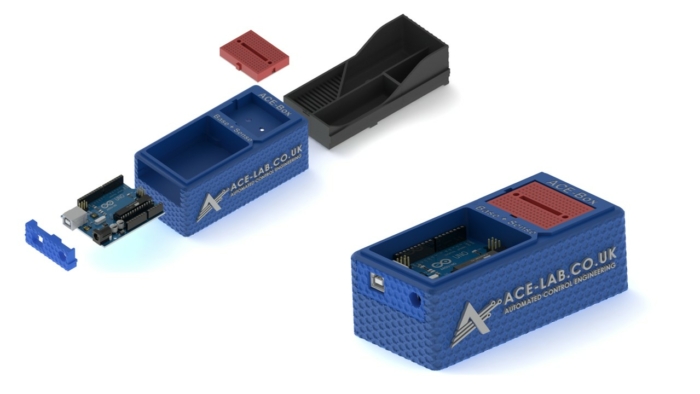

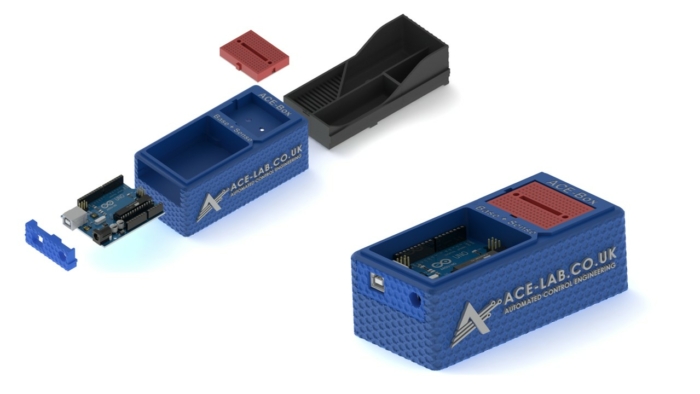

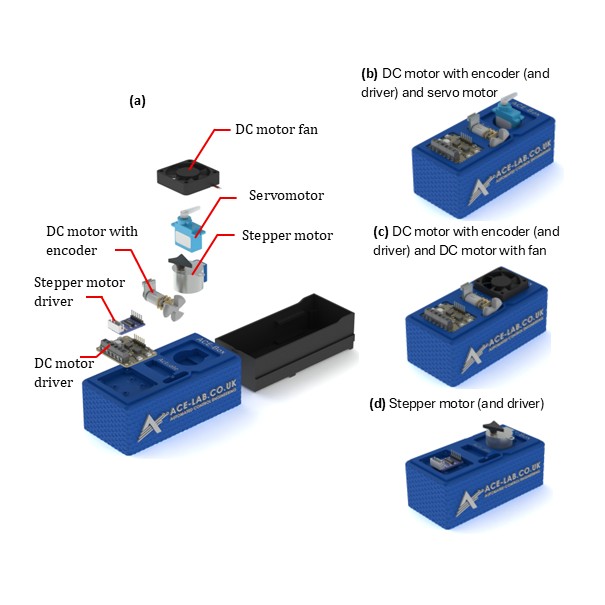

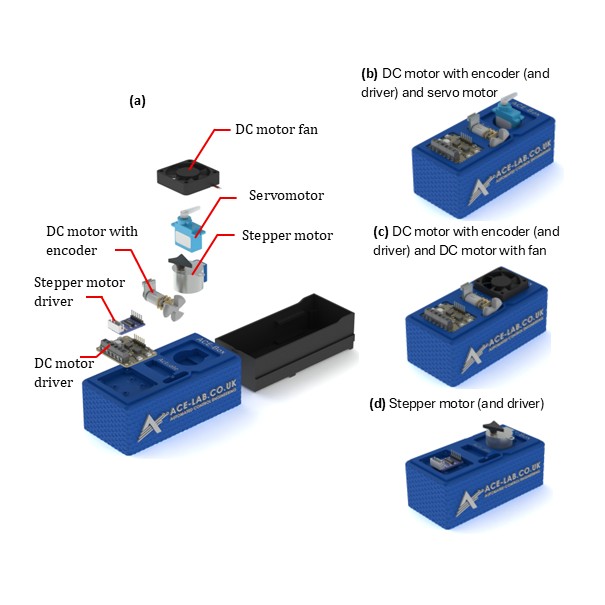

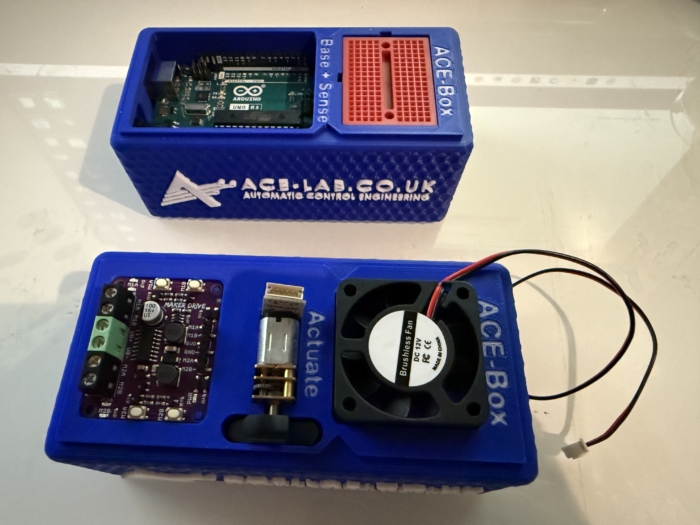

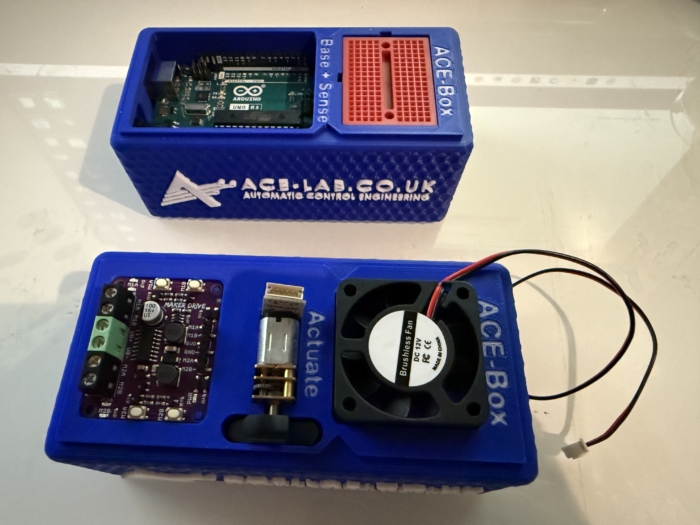

The ACE-Box (base and sense) is illustrated in Figure 3, with the 15 key components labelled, along with an exploded view of the main parts in Figure 4. The ACE-Boxes integrate the essential microcontrollers, electronics, sensors, and actuators needed to design, implement, and test elements of digital control algorithm development, e.g. control algorithms in real time. It bridges the gap between theory and practice, allowing learners to see how abstract concepts behave in physical systems. The ACE-Box is also available as an open-access resource, with laboratory exercises included, with details provided later in this article. The ACE-Box (labelled (1) in Figure 3) and the tray (labelled (2) in Figure 3) are manufactured using 3D printing, with the necessary files available on the project website referenced above. A list of the required components and their sources is also provided on the project website, corresponding to labels (3) to (15) in Figure 3. Due to the open-source design of ACE-Lab, the library of exercises will continue to expand, supported by contributions from both academia and industry. The ACE-Box (Actuate) is illustrated in Figure 5, with the key actuator components detailed in (a), along with some typical lab set-ups (b, c and d). Figure 6 illustrates both the ACE-Box (Base + Sense) and also ACE-Box (Actuate).

Figure 3: The ACE-Box (Base and Sense).

Figure 4: Assemble of the 3D Printed ACE-Box (Base and Sense).

Figure 5: The ACE-Box (Actuate).

Figure 6: ACE-Box (Actuate) Alongside the ACE-Box (Base + Sense).

ACE-CORE: The methodology:

ACE-CORE is a four-step framework designed to scaffold learning from components to system-of-systems understanding:

- Comprehend: Recognise the interdependencies between components within a feedback control system.

- Operate: Discover how to operate a control system from understanding system requirements to testing and validation.

- Refine: Diagnose, analyse, and optimise performance using feedback principles; students apply system verification and validation approaches.

- Engineer: Apply mathematics and modelling to synthesise control algorithms and architectures that achieve desired system behaviours.

The methodology explicitly develops systems thinking, and integration competencies, core to both AHEP4 and INCOSE frameworks.

ACE-CORE is intentionally designed to offer a scaffolded learning experience, allowing students to build confidence step by step as they deepen their understanding. Due to its flexible structure, students can also follow a completely practical route, i.e. avoiding the modelling and simulation. The emphasis is not on rote memorisation of theory, but on progression through understanding the fundamentals of control engineering, e.g. the components that form a feedback control system. These routes enable learners to apply concepts in practical control engineering contexts and develop genuine competence.

ACE-Apply: Real-world application:

ACE-Apply is the project stage, where the skills and knowledge gained from ACE-Box and ACE-CORE are consolidated by tackling authentic challenges aligned with the expectations of industry and professional engineers, see Figure 2(b). At this stage, learners prove their mastery by addressing engineering application problems that reflect the standards of industry practice. The focus is on:

- Applying the ACE-CORE methodology to practical control application challenges across domains such as robotics, automotive systems, drones, and industrial automation.

- Bridging theory, simulation, and hardware with confidence and agility using industry standard tools and processes.

This stage reinforces AHEP4 Themes 3 and 5, particularly:

- Applying integrated systems approaches to complex, real-world problems.

- Managing system lifecycle activities including requirements capture, design, testing, and validation.

It also strengthens INCOSE competencies in System Realisation, Integration, and Technical Project Management, encouraging students to act as systems integrators capable of managing interfaces and dependencies across mechanical, electrical, and software domains.

By bridging theory, simulation, and hardware using industry-standard digital tools, ACE-Apply nurtures the ability to navigate complex adaptive systems, anticipate emergent behaviour, and work collaboratively within multidisciplinary engineering ecosystems.

ACE-Box activities:

Upon visiting the ACE-Lab website (www.ace-lab.co.uk), under the tab ‘ACE-Box’, the following tabs exist (with the links provided):

The “What is the ACE-Box?” page introduces educators and students to the ACE-Box platform, outlining its purpose, key features, and practical considerations such as sourcing components and 3D-printing enclosure parts.

The “Prior Exercises” page provides essential onboarding material designed to help users become familiar with MATLAB and Simulink. This includes links to the relevant OnRamp courses, guidance on installing the required software packages, and short tutorial videos that introduce the MATLAB and Simulink graphical user interfaces (GUIs).

The “Base + Sense” section contains a set of introductory tutorial exercises that use the ACE-Box (Base + Sense configuration). These activities help users get started with Simulink code generation for the Arduino Uno, while working with a range of basic sensors and electronic components.

Finally, the “Base + Sense + Actuate” section builds on the previous material by introducing actuation hardware. Using both the Base + Sense and Actuate modules, students and educators learn how to interface with and control devices such as DC motors, servomotors, and stepper motors. This section is designed to familiarise users with actuator integration and reinforce practical control engineering workflows.

Example use of ACE-Box (Base + Sense):

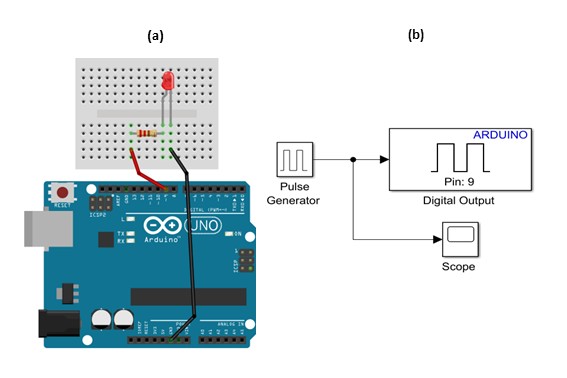

To demonstrate the use of the ACE-Box (Base + Sense), an introductory activity is provided, i.e. the on-off blinking of an LED. Prior to this activity, through ACE-CORE, students should receive a short introduction to microcontrollers covering key concepts such as digital input/output pins, analogue pins, and pulse-width modulation (PWM). Once students are familiar with these fundamentals, they progress to the initial exercise detailed here, which is aligned with defined learning outcomes.

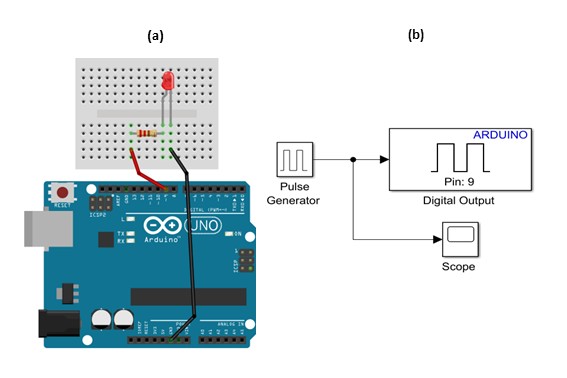

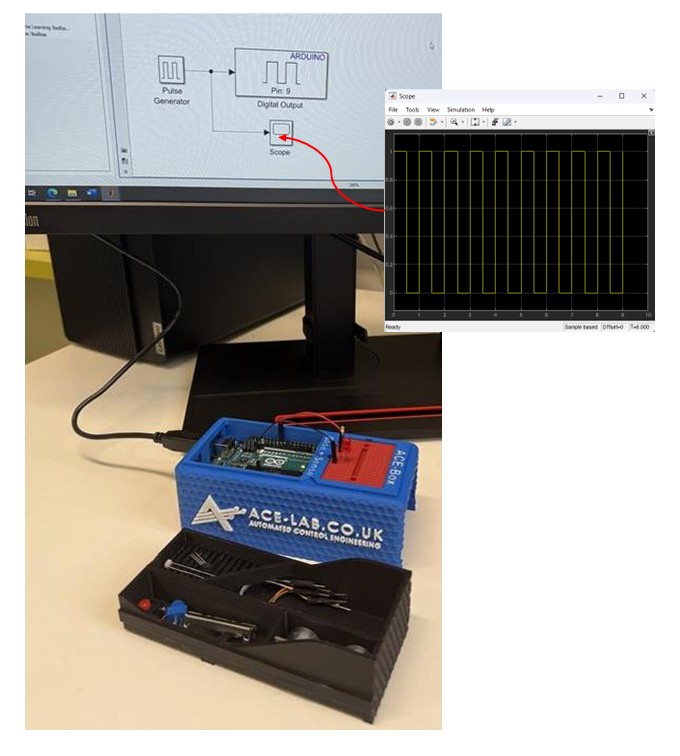

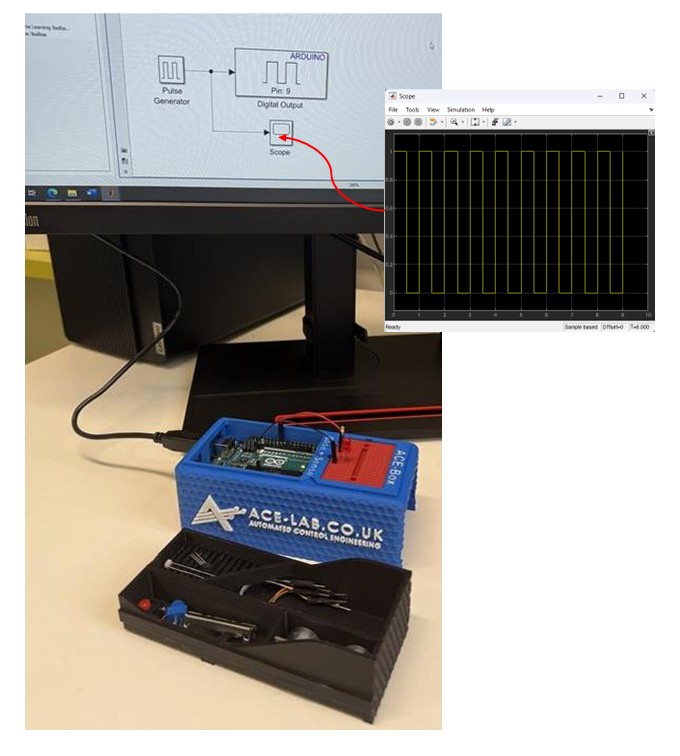

Since MATLAB and Simulink are the primary software tools used with the ACE-Box, students are first guided through installing the Simulink Support Package for Arduino Hardware. After the hardware and software setup is complete, they assemble a simple circuit, see Figure 7(a), and configure a Simulink model for the first exercise, see Figure 6(b). This initial activity requires students to control the state of a digital output pin on the Arduino, switching it on and off. The Simulink model, provided in Figure 7(b), enables students to quickly build the exercise using a visual programming approach. To run the activity, they follow a sequence of steps that includes code generation, which compiles the Simulink model into embedded C code and deploys it onto the Arduino Uno microcontroller. Once completed, the LED connected to the circuit blinks on and off according to the settings of the Simulink pulse generator. A visual of the complete set-up for this initial exercise can be found in Figure 8. At this stage, students are encouraged to experiment with the pulse generator parameters in real-time, observing how changes to the signal properties immediately affect the LED’s behaviour. Scopes can also be used (see Figure 7(b)) to visualise the pulse generator’s square-wave output, including its amplitude, period, and pulse width. This hands-on interaction reinforces the link between the initial set-up and hardware implementation while deepening their understanding of microcontrollers.

Figure 7: LED Simple Circuit (a) and Simulink for Code Generation for the on-off Blinking of an LED.

Figure 8: LED Simple Circuit Set-Up using Simulink for Code Generation for on-off Blinking of an LED.

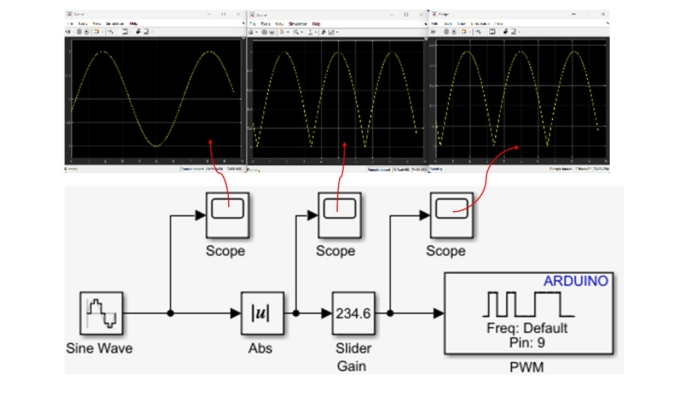

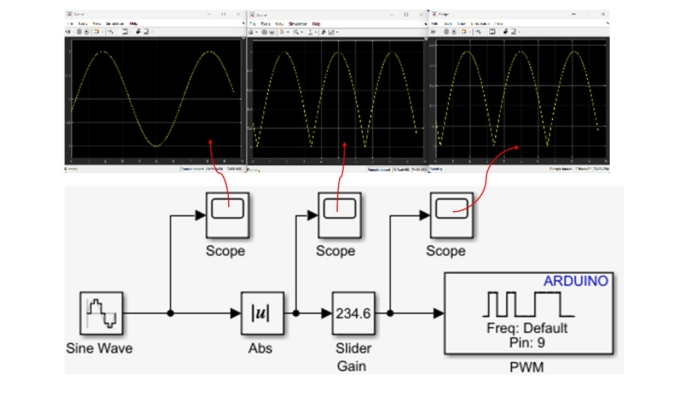

The initial exercise is designed to familiarise students with the ACE-Box and the use of Simulink’s code generation tools. This type of activity is typical for introducing students to a new software and hardware environment. The next exercise involves using pulse width modulation (PWM) to vary the brightness of the LED. This exercise involves using additional blocks in Simulink, see Figure 8, where multiple scopes are used to visualise the signals in real-time. Once students understand the fundamental building blocks of Simulink, they can quickly progress to developing feedback control systems that meet a variety of application requirements. In the authors’ view, student familiarity with Simulink makes it a more accessible platform for designing advanced control algorithms, particularly when working with sub-systems.

Figure 9: LED Simple Circuit Set-Up using Simulink for Code Generation Varying Brightness of an LED using Pulse Width Modulation (PWM).

Building on this foundation, a wide range of laboratory exercises can be developed using the electronic components involved in ACE-Box (Base + Sense), as illustrated in Figure 3, with the option to expand further by incorporating additional components. Examples of extended exercises include:

- Analogue sensing and calibration with a temperature sensor

- LDR characterisation and linearisation using a voltage divider

- Analogue sensing and calibration with a potentiometer sensor

- Digital sensing using an ultrasonic sensor

- Distance-reactive LED control with proportional feedback (human-in-the-loop plant)

- Closed-loop brightness control using LDR feedback and LED PWM

- LED–LDR plant control experiments

In addition to sensing activities, the ACE-Box (Actuate) provides four actuators: a servomotor, a DC motor with encoder, a stepper motor, and a DC motor fan. This unit can be used independently or in combination with the Base and Sense ACE-Box to enable more advanced control experiments, such as DC motor speed control or motor control based on light intensity measurements from an LDR.

The flexibility of the ACE-Box system ensures that the number of possible exercises is effectively unlimited, as new experiments can be designed by combining existing sensors and actuators or by integrating additional measurement devices. This also allows unique coursework assignments to be created.

Summary:

The ACE-Model provides a systemic and holistic framework for practical control engineering education that:

- Fosters systems thinking and model-based design literacy aligned with INCOSE and AHEP4 competencies.

- Connects abstract control theory to complex, real-world systems through accessible hands-on experiences.

- Encourages progression from component-level comprehension to system integration.

- Builds confidence and motivation through authentic engagement with digital and physical systems, preparing graduates for engineering practice in a complex, interconnected world.

Acknowledgements:

Dr James E. Pickering gratefully acknowledges the support from MathWorks, whose funding made this project possible. He also extends his sincere thanks to Hari Sudeskkumar for his exceptional engineering design contributions and 3D-printing work. The authors would like to thank the Project Advisory Group (PAG) for their valuable guidance throughout the development of this work.

References:

- Abou-Hayt, I. and Dahl, B., 2023. A Critical Look at the Laplace Transform Method in Engineering Education. IEEE Transactions on Education, 67(4), pp.542-549.

- Anderson, L.W. and Krathwohl, D.R., 2001. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives: complete edition. Addison Wesley Longman, Inc..

- Badau, N.E., Popescu, T.M., Mihai, M., Dulf, E.H. and Muresan, C.I., 2024. Bridging the gap between control theory and practice: From simple controller design to a practical microcontroller implementation. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 58(26), pp.124-129.

- Pickering, J.E., 2023. Control-Lab-in-a-Box: Bridging the Gap between Control Theory and Engineering Practice. In UK and Ireland Engineering Education Research Network Conference Proceedings 2023.

- Pickering, J.E., 2025. Leveraging Control-Lab-in-Box (CLB) to Teach Control Engineering on Future Vehicle Technologies MSc. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 59(7), pp.31-35.

- Rossiter, J.A., 2022. Future trends for a first course in control engineering. Frontiers in Control Engineering, 3, p.956665.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.