Author: Professor Manuela Rosa (Algarve University).

Author: Professor Manuela Rosa (Algarve University).

Keywords: Societal impact; Equity; Equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI); Design; Justice; Equity; Communication; Global responsibility.

Who is this article for?: This article should be read by educators at all levels in higher education who wish to integrate social sustainability, EDI, and ethics into the engineering and design curriculum or module design. It will also help to prepare students with the integrated skill sets that employers are looking for.

Premise:

The Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons, adopted by the General Assembly of United Nations on 9 December 1975, stipulated protection of the rights of people with disabilities. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a plan of action for people, planet, and prosperity, demands that all stakeholders, acting in collaborative partnership, must recognise that the dignity of the human person is fundamental and so the development of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals must meet all segments of society in a way that “no one will be left behind”.

In relation to engineering, The Statement of Ethical Principles published by the Engineering Council and the Royal Academy of Engineering in 2005 and revised in 2017, articulates one of its strategic challenges to be positioning engineering at the heart of society, enhancing its wellbeing, improving the quality of the built environment, and promoting EDI. To uphold these principles, engineering professionals are required to promote social equity, guaranteeing equal opportunities to access the built environment and transportation systems, enabling the active participation of all citizens in society, including vulnerable groups. The universal design approach is one method that engineers can use to ensure social sustainability.

The challenges of universal and inclusive design:

Every citizen must have the same equality of opportunities in using spaces because the existence of an accessible built environment is fundamental to guarantee vitality, safety, and sociability. These ethical values associated with the technical decision-making process were considered by the American architect Ronald Lawrence Mace (1941-1998) who defined the universal design concept as “designing all products, buildings and exterior spaces to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible” (Mace et al., 1991), thus contributing to social inclusion.

Universal accessibility according to this universal design approach is “the characteristic of an environment or object which enables everybody to enter into a relationship with, and make use of, that object or environment in a friendly, respectful and safe way” (Aragall et al., 2003). It focuses on people with reduced mobility, such as people with disabilities (mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive dimensions), children and elderly people. Built environment and transport systems must be designed considering this equity attribute which is associated with social sustainability and inclusion.

The Center for Universal Design of the North Carolina State University developed seven principles of universal design (Connell et al., 1997):

1. Equitable use

2. Flexibility in use

3. Simple and intuitive use

4. Perceptible information

5. Tolerance for error

6. Low physical effort

7. Size and space for approach and use.

These principles must always be incorporated in the conception of products and physical environments, so as to create a ‘fair built’ environment, where all have the right to use it, in the same independent and natural way. This justice design must guarantee autonomy in the use of spaces and transport vehicles, contributing to the self-determination of citizens.

The perceptions of the space users are fundamental to be considered in the design process to achieve the usability of the built environment and transport systems. Pedestrian infrastructure design and modal interfaces demand user-centred approaches and therefore processes of co-design and co-creation with communities, where people are effectively involved as collaborators and participants.

Achieving an inclusive society is a great challenge because there are situations where the needs of users are divergent: technical solutions created for a specific group of people are inadequate for others. For example, wheelchair users and elderly people need smooth surfaces and, on the contrary, blind people need tactile surfaces.

Consequently, in the process of universal design, some people can feel excluded because they need other technical solutions. It is then necessary to consider precise inclusive design when projecting urban spaces for all.

Universal design is linked with designing one-space-suits-almost-all, and inclusive design focuses on one-space-suits-one, for example design a space for everyone (collective perspective) versus design a space for one specific group (particular perspective). As the built environment must be understandable to and usable by all people, both are important for social sustainability. Universal design contributes to social inclusion, but added inclusive design is needed, matching the excluded users to the object or space design.

In order to promote social inclusion and quality of life, to which everyone is entitled, universal and inclusive co-design of the built environment and the transportation systems demands specific approaches that have to be integrated in engineering education:

- Universal and inclusive co-design aims at considering human diversity and that “it is normal to be different”.

- Universal and inclusive co-design requires strong collaborative approaches, through surveys, face to face interviews, walking with people with disabilities, elderly people, and other vulnerable groups.

- Universal and inclusive co-design must consider different components of the built environment and transportation systems, and requires connectivity and a strategic value chain approach.

- Universal and inclusive co-design demands cross-sectorial and interdisciplinary work, in transdisciplinary approaches.

- Universal and inclusive co-design benefits all the population.

- Universal and inclusive co-design is a fundamental tool for sustainable design.

Conclusion:

Universal and inclusive co-design of the built environment and transportation systems must be seen as an ethical act in engineering. Co-design for social sustainability can be strengthened through engineering acts. Ethical responsibility must be assumed to create inclusive solutions considering human diversity, empowering engineers to act and design justice.

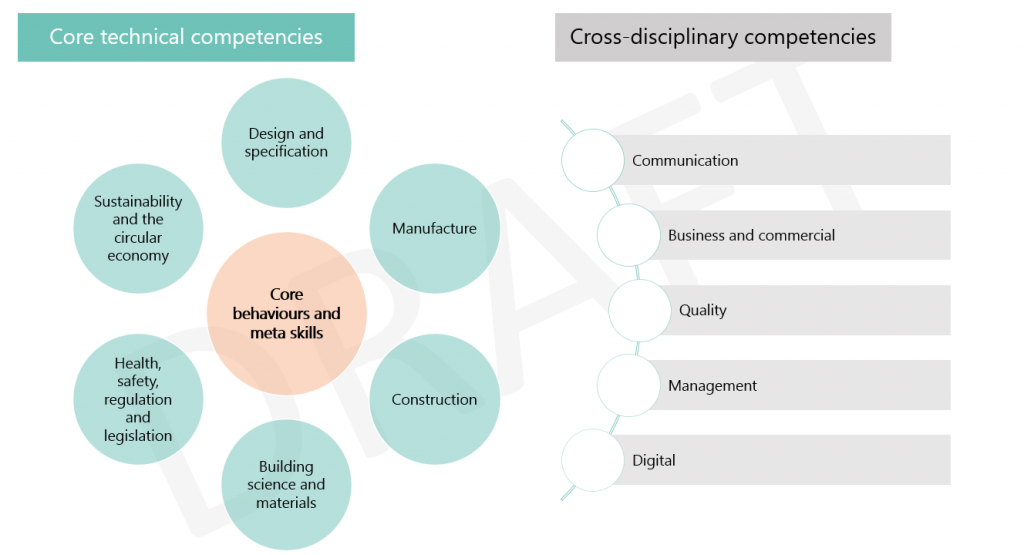

There is a strong need for engineers to possess a set of skills and competencies related to the ability to work with other professionals (for example from the social sciences), users, or collaborators. In the 21st century, beyond the use of technical knowledge to solve problems, engineers need communication skills to achieve the sustainable development goals, requiring networking, cooperating in teams, and working with communities.

Engineering education must consider transdisciplinary approaches which make clear progress in tackling urban challenges and finding human-centred solutions. Universal and inclusive co-design must be incorporated routinely into the practice of engineers and assumed in Engineering Ethics Codes.

References:

Aragall, F. and EuCAN members, (2003) European Concept for Accessibility: Technical Assistance Manual. Luxemburg: EuCAN – European Concept for Accessibility Network.

Connell, B. R., Jones, M., Mace, R., Mueller, J., Mullick, A., Ostroff, E., Sanford, J., Steinfeld, E., Story, M. and Vanderheiden, G. (1997) The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0. Raleigh: North Carolina State University, The Center for Universal Design. USA.

Mace, R. L., Hardie G. J. and Place, J. P. (1991) ‘Accessible environments: Toward universal design,’ in W.E. Preiser, J.C. Vischer, E.T. White (Eds.). Design Intervention: Toward a More Human Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 155-180.

Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons. (1975). Proclaimed by G/A/RES 3447 of 9 December 1975.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015, New York.

Additional resources:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Any views, thoughts, and opinions expressed herein are solely that of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies, or position of the Engineering Professors’ Council or the Toolkit sponsors and supporters.