The EPC has responded to the Office for Students (OfS) consultation on the future of the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF).

The policy statement is below, followed by the full question level response.

EPC TEF 2025 policy statement

By reframing TEF as a public announcement of institutional performance against the regulator’s B conditions, TEF moves even further away from a direct measure of teaching excellence. It becomes more conceptually confused, conflating student outcomes with teaching quality, and teaching excellence with regulatory compliance. Given this conflation, it is difficult to see how teaching excellence is assured in the proposed exercise, let alone fostered.

The unintended consequence may be to drive high-cost subjects such as engineering into decline. This would contradict national priorities for STEM capacity, industrial competitiveness and net-zero transition.

The Teaching Excellence Framework should be developed as an enhancement-oriented exercise, grounded as far as possible in evidence of educational gain and authentic teaching quality, not proxy metrics.

The extension of the TEF to all providers will create greater pressure to streamline the process, which might disadvantage nuanced programmes. For example, it is critical to Engineering that programmes are diverse in approach, innovation, mission, size, length, etc, and our work for the National Engineering Policy Centre/Royal Academy of Engineering’s Engineers 2030 shows widespread innovation in engineering. Under the proposed regime, the metrics would penalise providers who might want to expand or change their admissions to take more students who may face greater challenges in achieving the best outcomes. Moreover, it would make providers less willing and/or able to experiment, take pedagogic risks, or invest in innovation if penalties loom.

As shown in the Engineers 2030 work, engineering requires flexible, future-oriented and constantly developing pedagogy. TEF should encourage—not constrain—this evolution.

With European engineering education already perceived to be drawing ahead (a recent appraisal on the developments at Tecnico Portugal cites other European universities that have changed curriculum but ignores the UK – https://wonkhe.com/blogs/we-need-to-talk-about-culture) and given increasing international competition in Engineering HE, this is a threat to UK engineering education specifically, supporting the repeated narrative that things aren’t progressing here.

Foreseeable unintended consequences of the proposed approach include:

- Lagged data being ever more consequential (such that performance 5 or 10 years ago may undermine funding on a cumulative basis).

- Misguided applicant / student perceptions of individual course quality, especially internationally.

- The incentivisation of selectivity of inputs and applicant “creaming”.

- Cliff-edge funding boundaries in a spectrum context.

- Cumulative effects of fee penalties, driving quality downwards (especially in high-cost courses).

- Hidden and at-risk pockets of excellence.

- Provider-driven reductions in courses where the cost-to-outcomes ratio is unfavourable. This could include strategically important subjects such as engineering where outcomes are generally good, but costs are relatively high.

- Significant drivers for homogeneity among provider, stifling innovation and sector diversity.

- An English approach misaligned with UK and international standards of excellence.

- Significant risk of legal challenges to TEF ratings, given that even vexatious legal action would be made more worthwhile given the criticality of achieving higher ratings. This may not come from who institutions, but also schools and individual academics that are put at risk by outcomes data at odds with their performance.

Providers that achieve the highest levels of excellence are those that are least likely to be experiencing problems of funding and resources. On the other hand, while there are many reasons why other providers may not be achieving the same outcomes, in a context where so much of the HE sector is facing financial hardship, funding pressures are a likely factor.

It therefore seems perverse to award more funding to those providers that are excelling at current resource levels while increasing the problems for those that need most support to improve. Indeed, this seems an inefficient and ineffective use of limited public funding of fees. It is also worth noting that it would be the exact opposite of the approach in schools that has been effective in reducing the numbers of schools requiring improvement.

The consequence of such an approach over time will be to bifurcate the system into, on one hand, the winners in the TEF race with secure futures and funding growing at least as fast as needed and able to attract the highest-attaining, best-resourced students, and, on the other, those providers that slip behind, are penalised on a cumulative basis, and can never catch up, seeking constantly cheaper ways to deliver for their students, mopping up more challenging applicants who then receive a deteriorating education.

The second category of providers will close high-cost courses and may ultimately close, but not without creating opportunities for more predatory profit-driven providers and leaving significant gaps in HE provision both regionally and within certain disciplines.

Engineering, in particular, would be threatened as, even though its outcomes are generally good, it is a high-cost discipline. Moreover, because its outcomes are less dependent on regional prosperity (engineering economic activity is not especially focused in the South-East, for example) it may be the highest-performing discipline in a provider that is otherwise struggling to meet national comparisons of employment outcomes. Because it is not proposed that TEF makes any discipline distinctions (see below), cutting engineering departments – even successful ones – would be a rational commercial response to a poor aggregate TEF rating if that meant a reduction in unit resource.

Even if a provider that had suffered a fee penalty subsequently managed to raise its TEF rating, its fees would forever be reduced compared to providers that had never been penalised. This ensures what may be a short-term dip in quality (possibly due to extraneous factors) becomes a permanent blight on funding and substantially raises the stakes of TEF and the incentives to game the process, even if it means sacrificing long-term strategic planning for immediate outcomes.

If provider ratings are to be a primary lever for fee increases (or access to other funding), then institutions may game for metrics at the expense of strategically important provision (e.g., high-cost lab work, outreach, widening participation).

- We caution against incentives that drive providers to reduce high-cost, high-impact teaching (e.g., labs, placements) or marginalise widening participation activity that has long-run societal benefits.

- The OfS must also ensure that metrics do not penalise providers who admit diverse cohorts or women into engineering.

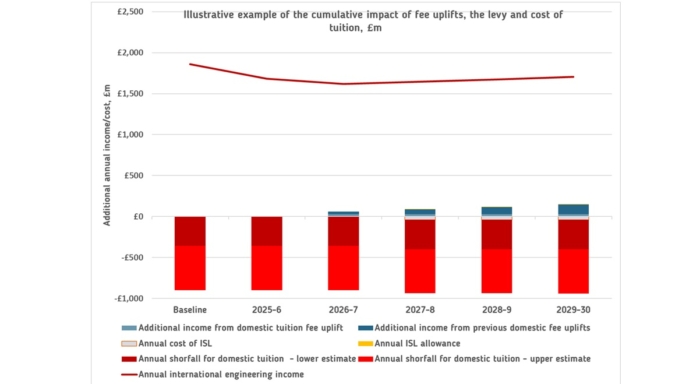

Engineering HE is systematically underfunded. The EPC estimates that income from home student fees and strategic priorities grants account for approximately two-thirds of the cost of teaching an undergraduate engineering degree. Meanwhile, departments are under more pressure than most to do more with less. We anticipate that they may feel more regulatory pressure than encouragement. Many providers and departments are undergoing major restructuring, including mergers, owing to the financial pressures within the sector. Unless the under-resourcing of high-cost courses is resolved, the TEF will drive perverse incentives to chase the courses that perform best in the metrics or search for the best trade-off between metric outcomes and low cost. Sometimes these effects will serve engineering positively, sometimes negatively, but, as a whole, it will harm the regional provision of engineering education, especially where it is most needed for growth.

The EPC has consistently called for greater subject sensitivity in the TEF, not broad provider-level banding. Provider-level metrics risk masking excellent subject pockets that are crucial to professional engineering supply and they encourage gaming through course selection.

With the rejection of subject-level TEF bandings, we welcome the use of subject-level indicators as contextual evidence within provider‑level TEF, and as a regulatory tool behind the scenes. However, we remain concerned that, because Engineering programmes are tightly coupled to internationally recognised professional standards, industrial relevance, hands-on learning, laboratories, placement years and competency frameworks, these nuances are not captured by institution-level metrics or generic student surveys.

Engineering degrees are commonly accredited by Professional Engineering Institutions (PEIs) under the auspices of the Engineering Council, where “outcomes”, or skill levels, are defined externally. Professional accreditation is the recognised measure of assured quality in engineering and needs to be properly recognised in the TEF.

Considering this in judging outcomes (e.g. how many graduates are in roles that match engineering competence rather than just “employed”) is more meaningful than broad outcome measures as it is less sensitive to economic climate and regional disparities in the labour market. It is extremely problematic that the TEF proposals do not integrate or align with professional accreditation.

Given that OfS has rejected a subject-level TEF, it should at least ensure the revised TEF allows subject-sensitive assessment beyond mere benchmarking, such as narrative evidence that recognises professionally accredited modes of delivery and practice-based outcomes. For example, “exceptional case statements” could allow engineering departments to explain context (e.g., high cost of labs, cohort heterogeneity, long placement leads).

The EPC supports disaggregating HTQ and degree-apprenticeship outcomes from standard degree outcomes. Many engineering providers deliver diverse L4/L5 provision and degree apprenticeships whose outcomes differ from full-time degrees so it should be expected that, at minimum, OfS applies separate indicators so engineering providers are not penalised for delivering important technical routes.

We are deeply concerned that the OfS has neither considered nor assessed the impact of the inclusion of integrated masters (which blur UG/PGT boundaries) and are a staple of “undergraduate” engineering provision across the UK. There seems to be no discussion in the proposals or sector about how 4- or 5-year integrated programmes should be treated under the 2025 design.

A B3 conditions heuristic should not be confused with a TEF, by name or application. OfS should avoid reductive medal ratings where the link to teaching excellence is proxy-based and tenuous. The further away from the “teaching excellence” exercise the measures are, the more likely undesirable consequences and gaming, particularly when perverse financial incentives are introduced.

A metrics reform is urgently needed. OfS should move away from tenuous proxies and adopt robust, discipline-relevant indicators, mapping educational gain and contextual narratives. Problems arising from lagged data, in particular, will be ever-more consequential (such that performance 5 or 10 years ago may undermine funding on a cumulative basis).

TEF risks misrepresenting engineering teaching context. Metrics must accurately represent learning and employability outcomes (and be robust to small cohorts and dilution by vocational HTQs/apprenticeships). The TEF metrics do not fully capture learning quality, skills development, professional readiness, and student experience. We would also welcome research into how student views change once they have entered the workplace.

Any outcome indicators used in TEF must control for factors such as student entry qualifications, socioeconomic and sociodemographic background, region, mode, course length and industrial placement years. Entry tariff or prior attainment could be applied as control variables allowing for the inclusion of “value-added” or progress metrics.

Qualitative evidence (industry engagement, placement quality, capstone projects, professional skills development) is essential in engineering and will require engineering experts (engineering academics or industry) on TEF panels when assessing engineering programmes.

The TEF should review the quantitative metrics and support these with evidence of authentic student experience: placement quality, employer assessment of graduate competence, and evidence of student development on professional skills.

Allowing for a balanced weight for narrative submissions (case studies, employer validation, student reflections) is necessary in engineering education, where project-based learning, capstone and group work are core.

We are also concerned about disproportionate burden on smaller, newer, or specialist providers, particularly those without mature data infrastructure or internal capacity to prepare submissions. Some may lack established TEF experience or may offer niche programmes only.

Small/specialist engineering departments may lack large central teams to compile submissions, let alone support online meetings or commissioned focus groups where the data is insufficient or statistically unsound. Engineering often has small cohort subjects where cohorts are small or heterogeneous (e.g., specialist MSc, sandwich cohorts) and contextualisation is needed. Not rating the student outcomes aspect may be detrimental.

Engineering tends to have higher-cost teaching elements (labs, workshops, equipment), project work, placements and field trips. These may lead to higher variation and occasional disruptions (equipment failure, lab closure, etc.). Without narrative or qualitative explanation, outcome metrics may penalise such disruption unfairly.

Q1a. What are your views on the proposed approach to making the system more integrated?

We support reduced duplication and burden, but in the process of simplification, it becomes more critical that the proposed measures of the system – such as TEF – have the structural integrity to bear the weight of their greater significance. If not, they run the risk of raising the existential stakes and rewarding institutions based on good fortune and gaming.

These proposals exacerbate the problems that extinguish necessary nuance and they fail to reflect the contextual spectrum at play both between and within providers.

By reframing TEF as a public announcement of institutional performance against the regulator’s B conditions, TEF moves even further from a direct measure of teaching excellence. It is undeniable that teaching excellence is not something that can be directly measured with ease, but that does not justify abandoning what counts in favour of what can be counted and misrepresenting the latter as the former.

It becomes more conceptually confused. It conflates student outcomes with teaching quality, and teaching excellence with regulatory compliance. Given this conflation, it is difficult to see how teaching excellence is assured in the proposed exercise, let alone fostered.

The unintended consequence may be to drive high-cost subjects such as engineering into decline. This would contradict national priorities for STEM capacity, industrial competitiveness and net-zero transition.

The Teaching Excellence Framework should be developed as an enhancement-oriented exercise, grounded as far as possible in evidence of learning gain and authentic teaching quality, not proxy metrics. A B3 conditions heuristic should not be confused with a TEF, either by name or implementation.

The extension of the TEF to all providers will create greater pressure to streamline the process, which might disadvantage nuanced programmes. For example, it is critical to Engineering that programmes are diverse in approach, innovation, mission, size, length, etc, and our work for the National Engineering Policy Centre/Royal Academy of Engineering’s Engineers 2030 shows widespread innovation in engineering. Under the proposed regime, the metrics would penalise providers who might want to expand or change their admissions to take more students who may face greater challenges in achieving the best outcomes. Moreover, it would make providers less willing and/or able to experiment, take pedagogic risks, or invest in innovation if penalties loom.

Given increasing international competition in Engineering HE, this is a threat to UK engineering education specifically, and we imagine other disciplines would be affected similarly.

Foreseeable unintended consequences of the proposed approach include:

- Lagged data being ever more consequential (such that performance 5 or 10 years ago may undermine funding on a cumulative basis).

- Misguided applicant / student perceptions of individual course quality, especially internationally.

- The incentivisation of selectivity of inputs and applicant “creaming”.

- Cliff-edge funding boundaries in a spectrum context.

- Cumulative effects of fee penalties, driving quality downwards (especially in high-cost courses).

- Hidden and at-risk pockets of excellence.

- Provider-driven reductions in courses where the cost-to-outcomes ratio is unfavourable. This could include strategically important subjects such as engineering where outcomes are generally good, but costs are relatively high.

- Significant drivers for homogeneity among provider, stifling innovation and sector diversity.

- An English approach misaligned with UK and international standards of excellence.

- Significant risk of legal challenges to TEF ratings, given that even vexatious legal action would be made more worthwhile given the criticality of achieving higher ratings. This may not come from who institutions, but also schools and individual academics that are put at risk by outcomes data at odds with their performance.

Integration must not “flatten out” disciplinary nuance: the engineering domain involves professional accreditation, lab-based activity, placement years, and cohort heterogeneity, and these must not be obscured by a generic overlay. We recognise the need to embed subject-sensitive flexibilities within the contextual information but urge OfS to ensure that integration does not translate into a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to assessment.

There is room in the proposals for greater granularity. We welcome the steps to help identify variation across disciplines, but maintain that a full subject-level exercise would make TEF better able to bear the weight of being more consequential. Without this granularity, the exercise is simply not sufficiently robust to assure quality, let alone enhance it. There is no point in simplicity if it drives undesirable outcomes and serves no one.

Even if a subject-level TEF cannot be contemplated because of the additional burden, there are still ways to allow providers to be more diverse and reflective of different missions, subject mixes and circumstances. For example, providers could be invited to select suitably ambitious target criteria for their measurement that align with their individual context. This would drive educational enhancement while the B3 conditions serve the quite distinct purpose of assuring satisfactory outcomes.

Q1b. Do you have views on opportunities to reduce duplication of effort between the future TEF and Access and Participation Plans (APPs)?

We caution against incentives that drive providers to reduce high-cost, high-impact teaching (e.g., labs, placements) or marginalise widening participation activity that has long-run societal benefits. The OfS must also ensure that metrics do not penalise providers that admit diverse cohorts, or women into engineering, for example.

OfS should publish explicit protections ensuring that providers admitting students from disadvantaged backgrounds or widening participation cohorts are not penalised for doing so. Outcome expectations must be moderated by student background, prior attainment and pathways.

A reduced burden is helpful, but conflating the two purposes is not. We recommend that the OfS publishes a mapping of overlapping indicators and a “transfer matrix” showing where APP and TEF data can be used.

That said, we do support a greater reflection within TEF of contextual information and the differing missions within which outcomes need to be achieved.

We would also welcome a process for TEF that is modelled on the Equality of Opportunity Risks Register, albeit for performance targets rather than risks. Just as each provider selects in its APP the risks from EORR that it chooses to prioritise, so too could providers select from a list of teaching excellence metrics those that it intends to target and be assessed on whether it manages to do so.

Q2a. What are your views on the proposal to assess all registered providers?

In principle, assessing all registered providers underscores fairness, transparency and accountability. We are concerned that increasing regulatory and compliance demands may erode institutional autonomy, reduce space for flexibility, and push more of the system into formulaic, “templated” responses.

The extension of the TEF to all providers will create greater pressure to streamline the process, which might disadvantage nuanced programmes. For example, it is critical to Engineering that programmes are diverse in approach, innovation, mission, size, length, etc, and our work for the National Engineering Policy Centre/Royal Academy of Engineering’s Engineers 2030 shows widespread innovation in engineering. Under the proposed regime, the metrics would penalise providers who might want to expand or change their admissions to take more students who may face greater challenges in achieving the best outcomes. Moreover, it would make providers less willing and/or able to experiment, take pedagogic risks, or invest in innovation if penalties loom.

Given increasing international competition in Engineering HE, this is a threat to UK engineering education specifically, and we imagine other disciplines would be affected similarly.

Engineering programmes often rely on local decisions (e.g. lab scheduling, project assignment, industry integration). Over-templated regulatory systems may constrain that local flexibility, which is a risk for innovation or responsiveness to industry change.

We are also concerned about disproportionate burden on smaller, newer, or specialist providers, particularly those without mature data infrastructure or internal capacity to prepare submissions. Some may lack established TEF experience or may offer niche programmes only.

Given that underperformance in TEF may represent an existential threat to an institution, this will heighted the incentives to game data or to sacrifice departments with a risky cost-to-outcomes ratio. That will be far more possible for large-scale providers.

Because many engineering providers already engage with accreditation and quality assurance processes, care must be taken not to duplicate (or undermine) effort.

Q2b. Do you have any suggestions on how we could help enable smaller providers, including those that haven’t taken part in the TEF before, to participate effectively?

The data strategy of the TEF is unsuitable for very small providers and with small cohorts and are susceptible to perceptions of ‘quality’ that have been established in very different contexts. Sourcing ‘alternative means’ of evidence of student views does not negate the risk of distorted judgements.

We would advocate for a risk-based approach to TEF and NSS participation, or a statistical approach suitable for small datasets that do not show normal distributions.

We suggest proportionate, light-touch submissions, phased roll-out, and reduced duplication. Integration must mean “collect once, use many times.”

Q3a. What comments on what provision should be in scope for the first cycle? (e.g. inclusion of apprenticeships, partnership provision)

We believe that limiting the first cycle to undergraduate degree programmes (with optional inclusion of apprenticeships under safeguards) is prudent to reduce complexity while the system stabilises.

Many engineering providers deliver diverse L4/L5 provision and degree apprenticeships whose outcomes differ from full-time degrees so we should expect that, at minimum, OfS applies separate indicators so engineering providers are not penalised for delivering important technical routes.

TEF should treat integrated masters structures (which blur UG/PGT boundaries) separately as an international reputation safeguard.

Q3b. Comments on proposed approach to expanding assessments to PGT in future cycles

There seems to be no discussion in the proposals or sector on how 4- or 5-year integrated programmes should be treated under the 2025 design.

Engineering has distinctive structures: most UK universities offer integrated MEng programmes, which blur undergraduate/postgraduate boundaries. Current proposals do not account for this. Without recognition of integrated MEng/PGT fluidity, metrics may be mis-timed, misclassified, or misinterpreted.

OfS should assess the impact of disaggregation (or not) of outcomes for integrated MEng cohorts to distinguish UG/PGT parts of integrated degrees, as well as apprenticeships, and PGT, or allow narrative explanation. Accreditation evidence should be given weight.

Q4a. What are your views on the proposal to assess and rate student experience and student outcomes?

There is a risk of perverse incentives or gaming: e.g. easier modules, avoiding riskier practical work, lowering cohort diversity/profile if this hurts metrics – and mission drift. The EPC has previously argued strongly against over-reliance on NSS data as a proxy for quality because they may reflect student demographics/circumstances more than teaching quality. As it is proposed that NSS data would be used in an aggregated way, the widely recognised differences in NSS responses between disciplines (which is more likely to reflect differences in the critical tendencies of the students who choose different disciplines rather than significant differences in how satisfactory those disciplines are) may lead providers to seek to influence TEF by adapting their balance of students across disciplines. In other words, cut certain courses to bump NSS scores. This has always been possible, but it has not had a noticeable effect, but it is an example of how if TEF is made more commercially critical, it will assume a greater power to cause unintended consequences.

The proposed benchmarking is unlikely to be adequate to mitigate these effects, not least because it will be based on lagged data (because the benchmarks may be set by a different timeframe to the data being compared).

In engineering, any credible experience dimension must allow recognition of intensive lab work, project-based group work, industrial site visits, and professional skills development.

OfS should publish explicit protections ensuring that providers admitting students from disadvantaged backgrounds or widening-participation cohorts are not penalised for doing so. Outcome expectations must be moderated by student background, prior attainment, and pathways.

Q4b. Comments on proposed approach to generating ‘overall’ provider ratings based on the two aspect ratings

OFSTED has recently moved away from the ‘single word judgement’ approach following tragic and scandalous consequences of such cliff-edge judgements and a wide consensus that the quality of a school cannot be fairly reflected into simplistic ratings. This regulator has sought to make assessments fairer and provide a more complete picture of performance. It also recognised that single word judgements are not effective in raising standards, which is better achieved through measures against each of the subcategories.

In this context, it is remarkable that OfS, the regulator of a far more complex set of providers, should decide to double-down on heuristic simplicity. At the very least, ratings for each aspect are needed. Outcomes need to be given as much context as practicable to avoid a narrowing of access and misrepresentation of true patterns of performance, especially in the absence of a subject-level TEF.

The EPC has consistently called for more subject sensitivity in the TEF, not broad provider-level banding. Provider-level metrics risk masking excellent subject pockets that are crucial to professional engineering supply. Even within engineering, disparate sub-disciplines are aggregated. We welcome the steps to help identify variation across disciplines but maintain that a full subject-level exercise would make TEF better able to bear the weight of being more consequential.

Narrative evidence should command equal weight. The use of multi-dimensional evidence including employer validation, professional body input, placement quality, and student engagement (UKES, learning analytics) should be embraced.

Accreditation by Professional Engineering Institutions is not merely contextual; it is the internationally recognised mechanism for quality assurance in engineering. TEF assessments should formally incorporate accreditation outcomes, where appropriate and permit accredited programmes to be benchmarked using discipline-specific criteria validated by the Engineering Council.

Q5a. Views on the proposed scope of the student experience aspect, and how it aligns with relevant condition B of registration

Condition B5 “Appropriate setting and application of the standards for awards” is not amenable to a differentiated rating. In an accredited engineering context, standards are aligned with PSRB requirements, and interrogated and affirmed in periodic accreditation visits. The primacy of this is such that the QAA Subject Benchmark Statements for Engineering directly reflect PSRB practice and standards. In this context, how does one ‘better’ meet standards, unless we are to infer that TEF will indeed reward ever-rising standards given its aim of ‘incentivising excellence above the requirements of the B conditions’. This is a signalled shift from criterion-referenced assessment to, e.g. norm-referenced assessment. Such a strategy would, of course, work in opposition to a quality framework aimed at facilitating comparison and benchmarking.

Engineering programmes often have non-standard delivery modalities (e.g. project weeks, lab rotations, fieldwork) that may not map cleanly to generic criteria. Some nuance or subcriteria should allow for that difference.

We suggest the criteria in corporate discipline-specific indicators (e.g. lab resource satisfaction, project supervision quality, access to specialist kit). TEF assessments should formally incorporate accreditation outcomes, where appropriate and permit accredited programmes to be benchmarked using discipline-specific criteria validated by the Engineering Council.

Q5b. Views on the initial draft criteria for the student experience rating (Annex H)

We believe the phrasing should explicitly accommodate discipline variation.

Q5c. Views on evidence to inform judgments about student experience

The EPC supports more nuanced measures of student engagement (e.g. UK Engagement Survey, learning analytics) rather than satisfaction surveys. Student voice must be balanced with richer engagement evidence. Discipline-adjusted survey items are suggested.

Q6. Comments on proposed approach to revising condition B3 and integrating minimum required student outcomes into future TEF

By reframing TEF as a public announcement of institutional performance against the regulator’s B conditions, TEF moves even further from a direct measure of teaching excellence. It is undeniable that teaching excellence is not something that can be directly measured with ease, but that does not justify abandoning what counts in favour of what can be counted and misrepresenting the latter as the former.

It becomes more conceptually confused. It conflates student outcomes with teaching quality, and teaching excellence with regulatory compliance. Given this conflation, it is difficult to see how teaching excellence is assured in the proposed exercise, let alone fostered.

The unintended consequence may be to drive high-cost subjects such as engineering into decline. This would contradict national priorities for STEM capacity, industrial competitiveness and net-zero transition.

The Teaching Excellence Framework should be developed as an enhancement-oriented exercise, grounded as far as possible in evidence of learning gain and authentic teaching quality, not proxy metrics. Minimum outcome expectations must be aligned with accreditation outcomes in Engineering. We caution that progression metrics (which track a student’s movement) may be overly simplistic, particularly in engineering with sandwich years and integrated masters.

Contextual factors (student prior attainment, entry route, demographic disadvantage, subject differences) must be built into all stages of outcome assessment — otherwise providers serving widening participation cohorts or complex disciplines will be penalised.

OfS should publish explicit protections ensuring that providers admitting students from disadvantaged backgrounds or widening participation cohorts are not penalised for doing so. Outcome expectations must be moderated by student background, prior attainment, and pathways.

Q7a. Views on proposed approach & initial ratings criteria for student outcomes

Outcome metrics punish providers who admit more disadvantaged students or recruit more women into engineering (since average salaries differ). We support the continued use of subject‑level benchmarking – as contextual evidence – recognising its value in identifying variation across disciplines.

However, value added metrics would be better overall. Teaching excellence is, after all, about the distance travelled towards potential rather than achieving a standard of attainment that might or might not reflect an acceleration in each individual’s development.

Lagged outcomes data, particularly when tied to financial incentives, risk penalising institutions for historical performance that predates current leadership or strategic improvement activity. This is especially damaging for engineering programmes whose employment patterns fluctuate with economic and industrial cycles. We acknowledge that OfS has sought to accommodate these effects by arguing that lagged and current strategic approaches will be reflected in due course, but by then, if providers have been penalised through fee income, they will be forever at a financial disadvantage because only an above-inflation fee increase would restore parity with other providers.

Q7b. Comments on the proposed employment / further study indicators, and suggestions of others

We recommend inclusion of employer validation metrics, professional body recognition, or alignment of graduate roles with engineering discipline.

Be cautious of overreliance on salary outcomes (which can be skewed by location, economic cycles), particularly disadvantaging engineering where salaries differ by gender, global mobility and what industries may be in a specific area.

Lagged outcomes data, particularly when tied to financial incentives, risk penalising institutions for historical performance that predates current leadership or strategic improvement activity. This is especially damaging for engineering programmes whose employment patterns fluctuate with economic and industrial cycles. We acknowledge that OfShas sought to accommodate these effects by arguing that lagged and current strategic approaches will be reflected in due course, but by then, if providers have been penalised through fee income, they will be forever at a financial disadvantage because only an above-inflation fee increase would restore parity with other providers.

Q7c. Views on proposal to consider limited contextual factors when reaching judgments

We endorse the inclusion of contextual factors (entry qualifications, socioeconomic and demographic background, part-time status, placement years and region) to adjust expectations and fair comparisons. This could and should go much further to fully recognise distinctive subject characteristics.

We hope we have understood correctly that this includes discipline-sensitive benchmarks (cross referenced against other benchmarks). This is essential to ensure adequate subject nuance in the contextual information.

The greater the level of benchmarking, the lower the risk that metric data incentivises gaming or rewards unintended and undesirable consequences. To some extent, benchmarking may ameliorate the ill-effects of aggregating data at provider level. It is not as effective as a subject-level TEF, but we recognise that it may be more easily achieved. To that end, we would encourage the OfS to benchmark across many factors and use only benchmarked data at every opportunity.

Q8a. Views on who should carry out assessments (and enabling more assessors)

Assessors and assessment panels must include discipline experts, specifically engineering academics or industry practitioners (engineers assessing engineering) so that technical nuance is properly understood.

Furthermore, many academic staff who are interested in these types of assessment may also be participating in academic accreditation on behalf of any one of the 39 Professional Engineering institutes licensed by the Engineering Council. We suggest there is, therefore, a real possibility of OfS being unable to appropriately resource its assessment regime.

Q8b. Views on only permitting representations on provisional rating decisions of Bronze or “Requires improvement”

We continue to dislike the use of heuristics as reductive to the point of massive over-simplification. The four-band system was so bad in schools, it’s been discontinued and HE providers are way more varied and complex than schools.

We are also concerned about the unfairness of not being able to appeal any judgement, especially if there are financial consequences. If there’s a material difference between silver and gold, appeals/review must be permitted. Failure to provide this opportunity is highly likely to result in legal challenges which may put the whole framework at risk.

Instead, a more multidimensional approach is needed to reflect granular performance against each condition. We recommend learning from the extensive exercise that OFSTED has undertaken in improving its framework. OFSTED previously had the excuse that its reporting needed to be easily understood by parents and other stakeholders. Given that the evidence is that TEF is not widely used to inform student decision-making, there is no reason not to adopt a more nuanced approach that better reflects the complex reality of diverse HE provision.

Q9a. Views on alternative means of gathering student views where NSS data are insufficient

Student surveys (NSS) are always insufficient; richer engagement measures (UKES, placement feedback) are more valuable.

There is little recognition of discipline nuance in student voice data. We recommend weighting qualitative evidence equally with metrics and ensuring representation from industry and accrediting bodies on TEF panels.

Q9b. Views on not rating student outcomes where indicator data are insufficient

A risk assessment is needed on the impact of this on smaller providers in terms of balanced assessment and student perception. It seems risky to determine financial incentives on a single rating for only some providers. It may also create perverse incentives to take steps to delay the availability of indicator data.

Q10a. Views on including direct student input for student experience assessments

Narrative evidence and alternative, discipline-level input should still be considered but the burden of this on small providers should be carefully managed.

Q10b. How to enable more student assessors from small, specialist and college-based providers

Q11a. Views on proposed scheduling of providers for first assessments

Many providers are undergoing major restructuring, including merger discussions owing to the financial pressures in the sector. Unless the under-resourcing of high-cost courses is resolved, perverse incentives to chase whatever courses perform best in the metrics or search for the best trade-off between metric outcomes and low cost. The scheduling with disadvantage some providers in any event.

Q11b. Views on scheduling subsequent assessments

Many providers are undergoing major restructuring, including merger discussions owing to the financial pressures within the sector. Unless the under-resourcing of high-cost courses is resolved, perverse incentives to chase whatever courses perform best in the metrics or search for the best trade-off between metric outcomes and low cost. The scheduling will disadvantage some providers in any event.

Maybe explore the use modular assessments rather than monolithic cycles (e.g. providers submit different evidence modules in different years).

Q12. Comments or evidence about risk factors to quality in draft risk monitoring tool (Annex I)

This is an opportunity to evidence the financial precarity of the sector. Staffing and financial stress indicators, infrastructure risks (lab maintenance, equipment renewal, software licensing, health & safety issues) and industry links / placement pipeline stability are all possible indicators.

Q13. Comments on proposed incentives and interventions associated with TEF ratings

We caution against incentives that drive providers to reduce high-cost, high-impact teaching (e.g., labs, placements) or marginalise widening-participation activity that has long-run societal benefits. A TEF that drives high-cost subjects such as engineering into decline contradicts national priorities for STEM capacity, industrial competitiveness, and net-zero transition.

If provider ratings become a primary lever for fee increases (or access to other funding) then institutions may game for metrics at the expense of strategically important provision (e.g., high-cost lab work, outreach, widening participation). The OfS must ensure that metrics do not penalise providers that admit diverse cohorts (such as, in particular, admitting more women into engineering).

If TEF ratings are tied to financial levers, engineering departments will be subjected to existentially raised stakes. Engineering HE is systematically underfunded, and departments are well versed in efficiency and cost-cutting reviews. They may feel regulatory pressure rather than encouragement. The more providers, the greater pressure to streamline — that might disadvantage nuanced programmes. It is critical to Engineering that programmes are diverse in mission, size, length, etc, and our work for the National Engineering Policy Centre/Royal Academy of Engineering’s Engineers 2030 shows widespread innovation in engineering. Under the proposed regime, the metrics would penalise providers who might want to expand or change their admissions to take more students who may face greater challenges in achieving the best outcomes. Moreover, it would make providers less willing and/or able to experiment, take pedagogic risks, or invest in innovation if penalties loom.

Given increasing international competition in Engineering HE, this is a threat to UK engineering education specifically, and we imagine other disciplines would be affected similarly.

Unless the under-resourcing of high-cost courses is resolved, perverse incentives to chase whatever courses perform best in the metrics or search for the best trade-off between metric outcomes and low cost. We caution that linking TEF rating to expansion or resource allocation may exacerbate inequalities between large, well-resourced providers and smaller/specialist ones. Provider-level TEF labels will be interpreted internationally at face value. Engineering relies heavily on international recruitment; broad-brush ratings risk misleading prospective students abroad, damaging an export sector worth billions to the UK economy and HE sector.

Incentives should be positive rewards (e.g. additional funding for improvement, innovation grants, recognition, support) not just penalties. The ability to raise fee in line with inflation is not a real-terms reward.

Lagged outcomes data, particularly when tied to financial incentives, risks penalising institutions for historic performance that predates current leadership or strategic improvement activity. This is especially damaging for engineering programmes whose employment patterns fluctuate with economic and industrial cycles. We acknowledge that OfS has sought to accommodate these effects by arguing that lagged and current strategic approaches will be reflected in due course, but by then, if providers have been penalised through fee income, they will be forever at a financial disadvantage because only an above-inflation fee increase would restore parity with other providers.

Q14a. Views on the range of quality assessment outputs and outcomes to publish

Simplistic ratings are misleading and damaging internationally. A provider “requires improvement” rating would be more so. Accredited and excellent Engineering would be seen as “substandard” abroad. Engineering has a heavily international student base and the financial precarity of the sector places great dependence on international fee income.

The absence subject-level TEF banding means that universities with excellence in engineering will be tarred by the brush of other subjects – or poor-quality engineering may escape due scrutiny thanks to other high-performing subjects. The same, of course, will be true for all disciplines.

Provider-level TEF labels will be interpreted internationally at face value. Engineering relies heavily on international recruitment; broad-brush ratings risk misleading prospective students abroad, damaging an export sector worth billions to the UK economy and HE sector.

Q14b. How to improve usefulness of published information for providers and students

We strongly oppose reductive TEF labels. International students and employers will apply the provider-level broad brush to engineering, risking reputational damage to engineering provision. The proposals do not go far enough to replace medal ratings with rich, contextualised dashboards.

Lagged outcomes data, particularly when tied to financial incentives, risk penalising institutions for historical performance that predates current leadership or strategic improvement activity. This is especially damaging for engineering programmes whose employment patterns fluctuate with economic and industrial cycles. We acknowledge that OfS has sought to accommodate these effects by arguing that lagged and current strategic approaches will be reflected in due course, but by then, if providers have been penalised through fee income, they will be forever at a financial disadvantage because only an above-inflation fee increase would restore parity with other providers.

Provider-level TEF labels will be interpreted internationally at face value. Engineering relies heavily on international recruitment; broad-brush ratings risk misleading prospective students abroad, damaging an export sector worth billions to the UK economy and HE sector.

We suggest publishing sensitivity / fragility analyses (e.g. how small shifts in student outcomes might move rating).

Q15. Comments on the proposed implementation timeline

Q16. Comments on the two options for publication of TEF ratings during transitional period (or alternative suggestions)

Q17. Comments on approach to ongoing development and plans to include PGT in future cycles

Many engineering programmes have integrated postgraduate levels built in (e.g. MEng). This means that student outcomes (graduation rates, employment, further study etc.) and experience may span longer times, more complex progression, and different cohorts (some in years that are postgraduate in level).

The integrated pipeline means that student experience in later years is qualitatively different (more research, more depth, more independence). But if TEF treats all years in one undifferentiated way, the later years may be judged by the same metrics as earlier ones, losing nuance.

For MEng programmes, the postgraduate years often embed more advanced, specialist, or research components tied to professional standards. If TEF metrics don’t recognise that extra work (or weight it properly), programmes might be penalised.

Q18. Aspects of proposals found unclear

By reframing TEF as a public announcement of the regulator’s B condition performance, the OfS is presenting an entirely different proposition to the existing framework. It is difficult to see where teaching quality itself is assured, let alone enhanced, by the proposed exercise. A TEF that drives high-cost subjects such as engineering into decline contradicts national priorities for STEM capacity, industrial competitiveness, and net-zero transition.

TEF remains conceptually confused: “better student outcomes” are not the same as “better teaching quality”. TEF should be developed as an enhancement-oriented exercise, grounded in evidence of educational/learning gain and authentic teaching quality, not proxy metrics.

That accreditation already assures quality in engineering remains unaddressed.

The interaction between TEF, APP and other regulatory regimes could use more mapping and worked examples.

It is not clear how the OfS intends to reflect context and use benchmarking in practice. We would encourage the widest possible use of both to mitigate the ill-effects of failing to conduct a subject-level TEF exercise and limit as far as possible the potential for data-gaming.

We look forward to seeing future proposals of the measurement of employment outcomes. However, without that detail it is impossible to assess whether the proposed plan may be critically undermined by systemic inequities and by gaming.

Q19. Additional suggestions for delivering objectives more efficiently or effectively

A better way to reward universities is to make TEF more meaningful to prospective students and staff, so it does become the driver of choice that it was first intended to be.

Replacing medals with dashboards would avoid single ratings and could be supported by scorecards showing strengths/areas for enhancement. Data does not feed into choice in simple ways and too much data becomes mere noise in the decision-making process. However, that does not mean that heuristic simplifications are preferable: as we have seen, they are not valued as informative and, at best, are used for post hoc rationalisation of choices that may be ill-informed and yet reinforced.

An interactive dashboard where students and staff can explore and prioritise the data that matters to them through comparative tools may be genuinely informative and useful.

We believe many of the concerns we have expressed about the proposals could be ameliorated by some or all of the following:

- The TEF (a measure of teaching excellence reflecting a complex and multidimensional relationship between provider and student) should not be conflated with the B conditions (compliance requirements with are more binary).

- Adopt a two-tier approach: Tier 1: Provider-level baseline (“meets B-conditions”) and Tier 2: Subject-level “profiles of strength”. This would provide nuance without full subject-level TEF.

- Take steps to encourage diversity and innovation through allowing providers to select ambitious target criteria from an EORR-style register of priorities.

- Use benchmarking and contextual information wherever possible.

- Do not link a narrow, proxy-based and heuristic TEF with funding.