We’ve all seen the higher education and national media coverage on the uncertainty around this year’s university admissions following the cancellation of exams and the extended UK-wide lockdown. The worldwide outbreak of Covid-19 has triggered widespread concerns about the impact on international students – the UK is among the sector leaders when it comes to the international student market, attracting tens of thousands of people to its universities every year.

Hopes for growth in this area on the back of Brexit were high, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government announcing last year its aim to grow the number of international students in the country by a third, supported by a new post-study work regime aimed at enhancing the flow of international students. While Gavin Williams has conceded that it’s “realistic” that we should expect international student numbers to fall, a recent QS survey has found that only one in seven overseas graduates and undergraduates due to study in Britain still plans to come. Meanwhile, research from the British Council indicates that half of young people in India and Pakistan who have applied to study overseas say they are “not at all likely” to change their plans. And a London Economics study predicts that around 120,000 international students will not appear, who would otherwise be expected to. Even if they want to come, just getting on flights would be a challenge right now.

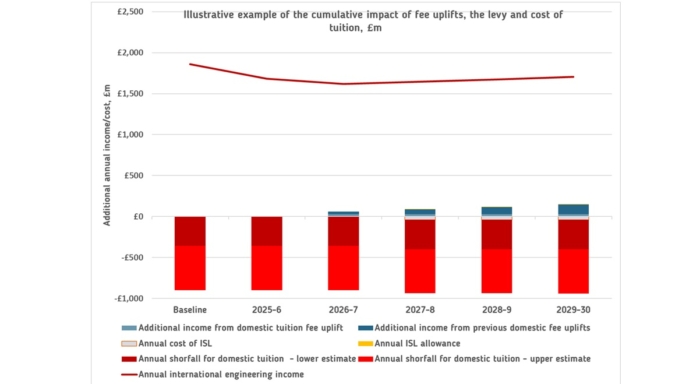

Universities UK estimates that the exposure on international fee income could be as much as £6 billion – and that’s before you add the knock-on economic contribution of international students to universities and local communities. With international recruitment such a key factor in many university’s financial strategies, there’s already close scrutiny of those universities for which tuition fee income is a critical component of their overall income and especially those which derive a larger proportion of their university tuition fee income from international students than from home students.

The EPC thought it might be helpful to look at the dilemma of international enrolment through the Engineering lens to help you engage fully with the flurry of activity around the health of this year’s international enrolments within your university.

As we know, Engineering is heavily dependent on overseas enrolments. In 2018/19, nearly one in three (32.4%) enrolments in Engineering and technology were from outside of the UK, nearly double the proportion across all science subjects and far greater than the one in five across all subjects. At postgraduate level, well over half (59.4%) of Engineering and technology enrolments were international last year. It’s about one in four at undergraduate (24.3%) and first degree (25.4%) levels.

As you might expect, it varies by discipline at both undergraduate and postgraduate level from 27.5% and 27.6% in Broadly-based programmes within engineering and technology and General engineering, respectively, to 48.6% international enrolments in Naval architecture. Table 1 shows the distribution of international and UK enrolments at postgraduate and undergraduate levels of study within Engineering and technology in 2018/19.

Understanding the shared international burden on Engineering is helpful, but a more nuanced approach to Engineering within your university is probably needed. Do you know, for example, how dependent your university is on tuition fee income in general and non-UK students in particular? And how does this relate to Engineering?

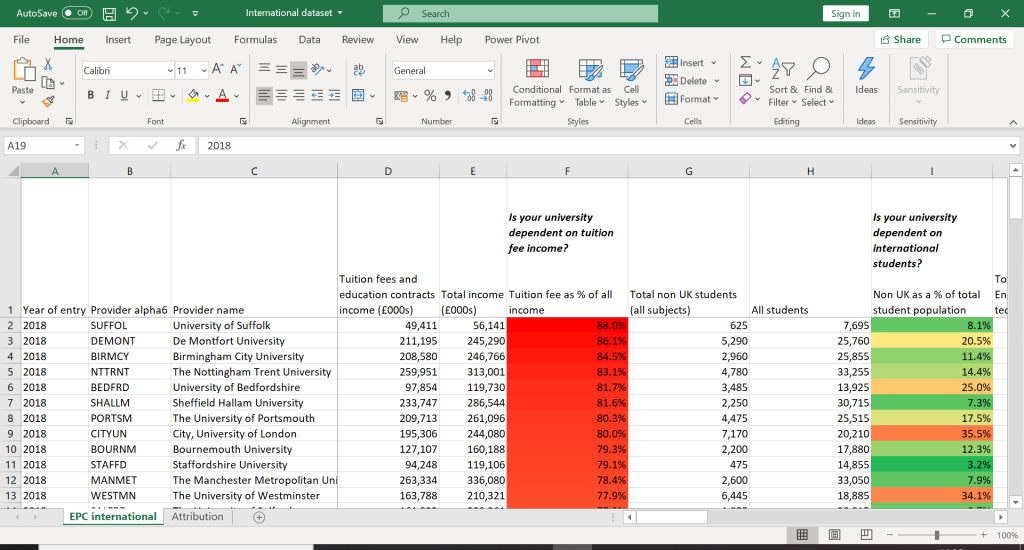

This information is publicly available through the latest Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) finance data which gives some indication of which universities are most dependent on fee income and – coupled with HESA student data at subject area [i] level – tell us which of our members are most exposed to a loss of international student income. So, we’ve created a basic reference table so EPC members can take a look. Below are some of the key questions it raises.

Is your university dependent on tuition fee income?

Is your university dependent on international students?

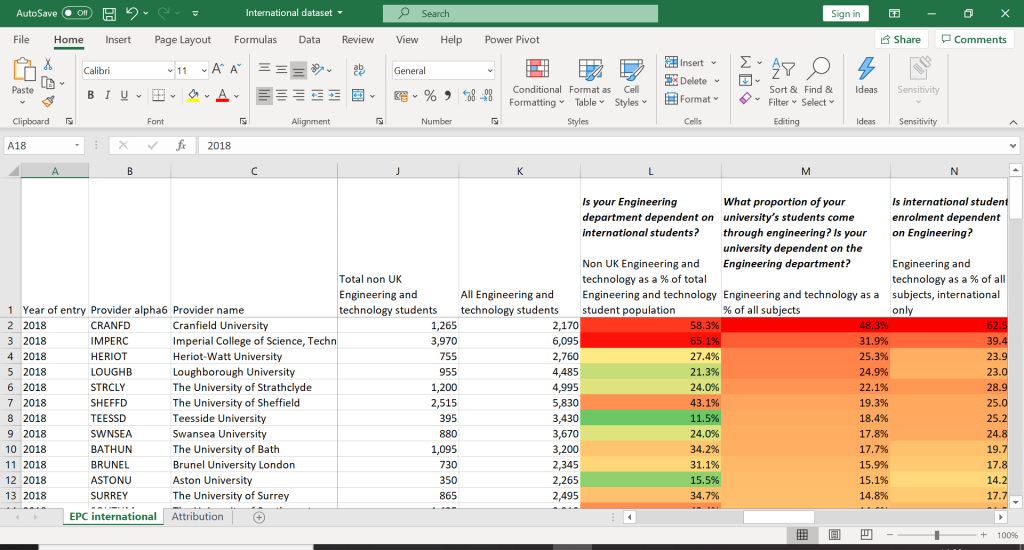

Where international fees are pivotal to your university strategy (meaning your senior leadership, planning and finance teams are almost certainly all over this), you might already be aware of your department’s role in this. What proportion of your university’s students come through Engineering? Further, is your international student enrolment dependent on Engineering?

Is the Engineering department dependent on international students?

What proportion of your university’s students come through Engineering? Is the university dependent on the Engineering department?

This is a double-edged sword for Engineering: yes, you’ve got a direct funding gap; no, you’ve still got problems given the inevitable pressure to cut costs and the higher international fees being widely understood to offer a surplus that supports high cost courses or loss making activity elsewhere (notwithstanding the likely loss of research income, especially among universities who work closely with business).

What if – at a glance – your university has a diverse income stream, and/or a good balance between domestic and international enrolments? Then you might need to flip the above questions on their head and ask if the Engineering department is more (or less) dependent on international enrolments than the university as a whole? If enrolments are heavily international in Engineering when, in general, they are not at your university, then this could be a problem. It might be timely to check it’s on the radar and to ensure that you and your Engineering colleagues are part of the discussion and the solution.

Is international student enrolment dependent on Engineering?

If Engineering enrolments are not internationally dependent while those of your colleagues in other subjects are, should you be looking to prop up the other subjects with extra home recruitment?

After all, in times of recession local demand can increase, and what about mopping up those UK students who might otherwise go abroad to study? Or, with the whole sector at risk, is now really the right time to make a dash for bums on seats (even within the 5% cap that the Government has now announced for English universities)?

Acknowledging the heterogeneity of Engineering departments within their wider environments, it would be careless to assume international students are homogenous. So, where do our international students come from?

They come from China – at least in (significant) part. You probably recall last summer’s media headlines of a 32 per cent rise in accepted applications from China, contributing to the new record of students accepted from outside the EU. China is also the major exporter of HE students to Engineering (and has been for many years).

Is the university’s international enrolment dependent on Asian students?

Is the Engineering department’s international enrolment dependent on Asian students?

And in Europe (remember that – for now – the finances for students from the EU are still equivalent to home students) compare HESA’s Non-UK Domiciled Student FPE dashboard (above) with Google map’s covid-19 map (https://google.com/covid19-map/) and you’ll see a reliance of Engineering on some parts of Europe worst hit by Covid-19. And from a European perspective, this disruption to the international student market comes at the worst possible time in terms of the uncertainty we were already facing, because the sector has no clear idea about how Brexit would have impacted EU student numbers even without Covid-19.

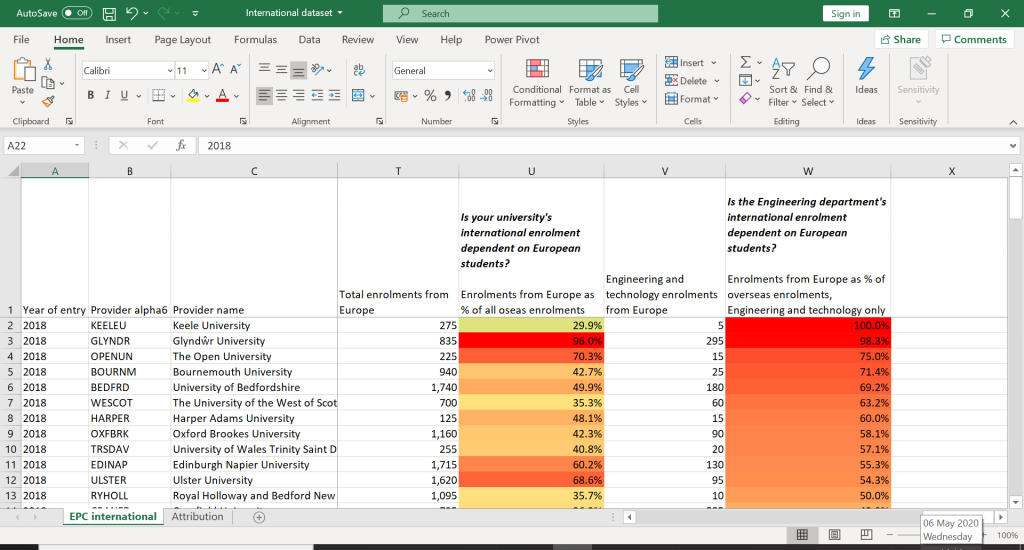

Is the university’s international enrolment dependent on European students?

Is the Engineering department’s international enrolment dependent on European students?

Of course, the Google map clearly shows how countries have been affected to different degrees by the virus and by lockdowns and we should expect that normality will resume in some countries sooner than others. Could this lead to international students preferring other HE destinations of choice, not least Canada, Australia and USA, or could we simply defer our international recruitment?

How we cope with recruitment problems now may determine how we deal with what we hope might be potential capacity problems later.

[i] JACS subject area 9 – Engineering and technology

Attribution: HESA HEIDI+ Non-UK Domiciled Student FPE dashboard, analysis of HESA Finance Record 2018-19 Table 1 and HESA Student Record Full Person Equivalent (FPE) v1. Copyright Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited. Neither the Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited nor HESA Services Limited can accept responsibility for any inferences or conclusions derived by third parties from data or other information obtained from Heidi Plus