The EPC has responded to the House of Lords Industry and Regulators Committee inquiry into the Office for Students (OfS), the regulator of the higher education sector in England. The response was countersigned and fully supported by the Engineering Council.

The Engineering Council is the UK regulatory body for the engineering profession. They hold the national registers of over 228,000 Engineering Technicians (EngTech), Incorporated Engineers (IEng), Chartered Engineers (CEng) and Information and Communications Technology Technicians (ICTTech). The Engineering Council also sets and maintains the internationally recognised standards of professional competence and ethics that govern the award and retention of these titles.

In addition, the Royal Academy of Engineering submitted their own response to reinforce select positions submitted to the same inquiry by the EPC.

The Royal Academy of Engineering is the UK’s national academy for engineering. We are a charity delivering public benefit, and a Fellowship bringing together an unrivalled community of leaders from every part of engineering and technology.

EPC response (April 2023)

these duties, and have some duties been prioritised over others?

The OfS was conceived as a regulator, to enable an established HE ‘market’. Regulation might therefore have reasonably consisted of interventions and rules where existing market forces were such that the market was unable to deliver.

However, there is evidence currently of the market no longer working as intended as a consequence of the regulator’s intervention, that is, where OfS has created the conditions leading to market failure. Within our detailed responses below, we highlight that the OfS:

• focuses on student outcomes that create incentives which are at odds with OfS\ statutory interest to support access and participation;

• is not developing regulations focused on a good student experience;

• has too narrow a view of student outcomes;

• fails to appreciate the existing regulatory landscape at discipline level, in particular in Engineering;

• is lowering standards below those professionally acceptable;

• is subject to English political influence leading to fracture from the devolved nations.

We understand the provision of Higher Education to have four main aims:

1. Exchange value: the development of skills and knowledge in order to pass the required assessments and gain a “qualification” that will allow the individual to access career choices that are not possible without this qualification;

2. Use value: the development of skills and knowledge for use in employment and everyday life;

3. Self-actualisation: the benefits for mental and spiritual wellbeing given to an individual when they are able to reach their full potential;

4. Education of the next generation: by educating one generation, we are providing the generations to come with a support-network better able to nurture their educational needs.

The regulator’s approach appears to only recognise the first of these purposes, evidenced through its prioritisation of employment in the B3 metrics based on an assumption that power and money are key measures of educational quality. Not only does this approach support out-of-date thinking around measuring success through high-achieving entrants going on to earn large salaries, it also neglects the remaining of the above three aims, all of which define the wider student experience.

We fear that OfS has got it wrong measuring success through blunt employment outcomes that embed social hierarchies and privilege. A high-quality course is not one with the best students, but the one whose students gain the most from their educational experience. It would be better to appraise providers on the basis of learning and employability gain (and distance travelled). Value added is at least as important as results to create the workforce of the future. In engineering, this is reflected in improvement and transformation awards and scholarships activities by Professional Engineering Institutions such as the IET, IChemE, IMechE and others and in the focus of employers on student diversity, not necessarily the ‘best’ students.

Outcomes can only ever be a proxy measure, given the extensive evidence that they are highly influenced by region, by national and regional economic conditions, by industrial sector and by imbalances in recruitment practices (gender, socio-economic background, etc.). These causal effects are ignored by the OfS and the reality is that, as outcomes are only indirectly related to factors within the HE providers’ control such as the quality of teaching and support, regulation based on a measure of quality against minimum baselines in relation to successful employment outcomes is at best inefficient and ineffectual. At worst, it encourages unintended consequences and ‘gaming’ and is damaging the sector. For example, the easiest way for an institution to improve its outcomes may be to axe certain courses or be less accessible to students from underrepresented backgrounds. This is contrary to the wider interests of students or the national interest.

OfS has a statutory duty to promote access and participation, and, in practice, these aims are often at odds with the regulators’ other aims, framework and measures.

There is now over-regulation of the highest quality courses in the sector. Engineering, for example, is heavily regulated: in any accredited Engineering course there is already a clearly defined set of standards, governed by the Engineering Council and assured by Professional Engineering Institutions. In addition, conflicts in standards (where the OfS’s are lower) have occurred, creating a resultant threat to international parity and reputation across the engineering profession.

framework developed over time, and what impacts has this had on higher education providers?

The role of the regulator should be to ensure the market operates effectively and to apply controls where market forces do not drive desired outcomes or work in opposition to them. However, OfS’s development of the regulatory framework has not evidenced sufficient grasp of how student factors, including widening participation and protected characteristics, influence and are influenced by different institutions, different disciplines and different regions. A 2016 Institute for Fiscal Studies study showed that one of the most significant influences was whether they came from an already wealthy background with school attainment a stronger predictor of graduate earnings than subject or university choice.

We are concerned that there is a clash of interests in the way OfS is pursuing the B3 conditions agenda and their statutory regard for access. OfS has set measures that run counter to its mission to ensure that all students, whatever their background, are protected from low-quality courses or qualifications that do not meet sector-recognised standards.

These measures disincentivise HEIs from taking a risk on potential students from certain disadvantaged backgrounds. For example, evidence shows that drop-out rates are higher among students with extra financial or social challenges, and bias in recruitment practice disadvantages certain graduates. If students are from lower socioeconomic or minority ethnic backgrounds, or they are disabled or they are returners to study, their course might look ‘low quality’ while actually the prospects of those students (compared to not having achieved that degree) have been greatly improved.

As a result, universities and courses could end up being sanctioned for reasons to do with a) their subject mix and b) their intake, rather than anything that they might actually be doing wrong; trying to do the right thing may open universities up to sanctions. Conversely, some providers may develop strategies to recruit high-performing, socially advantaged students with the result that universities will be rewarded for doing as little as possible to close the gaps. OfS’ direction of travel is therefore likely to narrow fair access, rather than improve higher education.

We are also concerned that providers, as a result of the OfS’s new approach to quality and standards are incentivised to lower standards. Engineering accreditation standards are high, but if meeting accreditation standards threaten performance metrics, universities may opt not to be accredited rather than risk letting students fail or drop out. This is a threat to standards. The Engineering Council has already had to regulate with regards to compensation and condonement (university regulations that permit students to progress on and be awarded degrees despite failing modules) to ensure standards are maintained on accredited degrees. This is because HEIs are increasingly permitting students to progress and be awarded a degree despite levels of failure that the profession would consider unacceptable, thus allowing students to graduate without demonstrating all the required learning outcomes. This, in turn, means graduates do not have the knowledge and understanding required to perform their roles in a manner commensurate with minimum health and safety expectations, for example. The societal impacts of this are potentially huge.

right balance between providing guidance and maintaining regulatory independence?

The OfS focus on responding to Government, on issue such as freedom of speech, appears to be at expense of wider stakeholders.

We are especially concerned that OfS has not engaged with existing regulation in the HE sector. Engineering is heavily regulated: in any accredited Engineering course there is already a clearly defined set of standards, governed by the Engineering Council and assured by Professional Engineering Institutions. Indeed, PSRBs already set standards in terms of learning outcomes in Engineering (and many other professional higher education courses).

We also note that, despite echoing the political rhetoric of Government ministers, the OfS approach to quality and standards conflicts in parts with the detail of Government policies, including on HE funding, degree apprenticeships, international student targets and lifelong learning. That may mean that all regulatory efforts to create incentives will be a waste of resources as HEIs are pulled in multiple directions simultaneously.

expertise been affected by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education’s decision not to continue as the

OfS’ Designated Quality Body?

This includes the Engineering Subject Benchmark statement which, alongside the UK Quality Code, and the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG) has UK wide value in relation to Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Bodies (PSRBs). An opportunity has been missed to make better use of existing regulation frameworks (such as Ofsted in relation to degree apprenticeships and accreditation in relation to professional courses), where on the ground evidence of high quality is recognised as a positive indicator without deferring to deficit model proxy measures. Dismissal of sensible and established regulatory and professional outcomes which already hold providers to account, at subject level, has led to over-regulation of the highest quality courses in the sector.

We understand that at least part of why QAA gave up their DQB status in England was because they couldn’t continue to align with international standards at the same time as confirming to expectations from OfS and/or Westminster. Internationally recognised professional accreditation incorporating QAA documents is a mainstay of the high regard around the world for the UK’s HE system and the massive economic benefit of the internationality of engineering. This is very real example of where OfS has negatively impacted the HE market.

It is not clear to us how the OfS works closely with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, when OfS’s approach in relation to quality and standards is no longer in alignment.

OfS appears to be disproportionately focused on the perceived economic impacts of a degree at the expense of other things. By prioritising employment in its B3 metrics, the OFS takes as its base assumption that power and money are the only measures of success. Real value for money would reflect distance travelled not existing advantage; the Institute for Fiscal Studies study (already referred) showed that one of the most significant influences on outcomes was whether students came from an already wealthy background with school attainment a stronger predictor of graduate earnings than subject or university choice.

of their interests and its regulatory actions to protect those interests?

The OfS has demonstrated minimal regard to sector responses to their consultations and has been unreasonable in the timescales and volume of responses expected to what have been excessively long consultations. “The Office for Students (OfS) published 600,000 words in regulatory documents in 2020–21, almost double the word count of 2017–18. Last January, the OfS issued 699 pages of consultation documents with a two-month response deadline, at a time when we were planning for an Omicron-induced lockdown.” (Richardson).

The EPC has raised concerns directly with the OfS that their strategy both pre-judged sector support for the proposals set out in the OfS quality and standards consultations and did not pay due regard to the sector feedback. We are mindful that the OfS’s response to the phase one quality and standards consultation and to subsequent thinking on the follow-up consultation, did not take proper assessment of criticism from a “large proportion of respondents”, including the EPC.

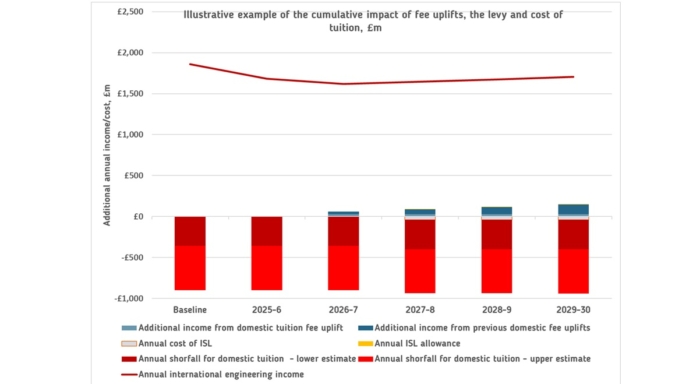

Engineering is clearly a strategically important subject, pivotal to the UK economy, but is underfunded in UK higher education. The tuition fee level is below the actual cost of tuition (TRAC), which is on average nearer £11,500. As a result, Engineering is significantly subsidised by international fees and is successful in attracting an unusually high proportion of international students. In 2018/19, nearly one in three enrolments in Engineering and technology were from outside of the UK, nearly double the proportion across all science subjects and far greater than the one in five across all subjects.

OfS’s approach to regulation is extremely damaging to this important area, systematically undermining UK engineering’s existing international regulation.

the financial risks of the sector, and are universities focusing sufficiently on having a viable business model?

OfS’s position and powers have incentivised homogenous approaches designed to deliver metric-satisfying outcomes rather encourage innovation, which presents a threat to home and international income generation through fees.

Universities contribute hugely to our economy. Latest estimates indicate that the higher education sector supports over 815,000 jobs in England alone and contributes more than £52 billion in GDP.

We estimate that overall student fee income in engineering accounts for approximately 10% of the fee income to the sector as a whole. In 2021, HEPI estimated that hat just one year’s intake of incoming international students is worth £28.8 billion.

Engineering is clearly a strategically important subject, pivotal to the UK economy, but is underfunded in UK higher education. The tuition fee level is below the actual cost of tuition (TRAC), which is on average nearer £11,500. As a result, Engineering is significantly subsidised by international fees and is successful in attracting an unusually high proportion of international students. In 2018/19, nearly one in three enrolments in Engineering and technology were from outside of the UK, nearly double the proportion across all science subjects and far greater than the one in five across all subjects.

OfS’s approach to regulation is damaging to this important area, systematically undermining UK engineering’s existing international regulation. The Engineering Council, the UK regulatory body for the engineering profession, is a signatory to a number of international accords which support international recognition of accredited engineering degrees. Accord reviews have highlighted that by permitting and incentivising compensation and condonement OfS risks damaging international recognition of UK engineering degrees.

place to manage provider failure? Would the failure of a large provider follow a clear regulatory process or is there the potential for political considerations to play a role in such decisions?

funding rather than the OfS’ regulation? Is there a need for policy change or further clarity to ensure the sustainability of the sector?