The EPC has responded to the Engineering UK Inquiry call for evidence – Fit for the future: Growing and sustaining engineering and technology apprenticeships for young people.

The aims of the inquiry were to:

- examine the reasons behind the decline in engineering, manufacturing and technology apprenticeships over time

- better understand the barriers facing young people in pursuing apprenticeships in engineering, manufacturing and technology

- identify solutions and good practice which could help to increase the number and diversity of young people starting and completing engineering, manufacturing and technology apprenticeships

- contribute to the wider debate about skills reforms, including, for example, Sir Michael Barber’s review

The full response is outlined below.

EPC response (February 2023)

The Engineering Professors’ Council (EPC) is the representative body for engineering academics (at all levels – not just professors) in higher education. There are currently 75 institutional members encompassing over 7,000 academic staff (permanent FTE). There are also Partners, including Royal Academy of Engineering.

Our primary purpose is to provide a forum within which engineers working in UK higher education can exchange ideas about engineering education, research and other matters of common interest and to come together to provide an influential voice and authoritative conduit through which engineering departments’ interests can be represented to key audiences such as funders, influencers, employers, professional bodies and Government.

Our response, therefore, focuses on degree apprenticeships and the need to put the learner front and centre of this debate. As engineers our responses do, of course, tend to the solutions.

EPC members (most HE engineering departments in the UK) have been forging the changes in this area from the outset, and the EPC has supported this work by sharing the voice of academic experts through collaborations, forums, working groups and reports. Our initial discussion paper ‘Designing apprenticeships for success‘ focused on: apprentices’ experience and outcomes; collaboration between HEIs and employers; accreditation and assessment; funding; and parity of esteem. This was followed by Experience enhanced: improving engineering degree apprenticeships which included reflections and recommendations. Details of these are included in the solutions section, below.

years? We are particularly interested in understanding more about supply and demand.

Degree apprenticeships are a growth apprenticeship area, perhaps because they offer some clear advantages to both apprentices and employers in comparison with traditional degree pathways. For degree apprentices, there is the opportunity to avoid student debt and to have greater employment security. For employers, the costs are comparable to graduate recruitment and learning can be shaped to their specific needs.

Larger employers – those paying the levy – have the most to gain and are best able to take advantage of the opportunity. However, even with these advantages, degree apprenticeships remain a less appealing prospect for small and medium-sized enterprises. The regulatory burden is seen to be onerous. When coupled with the need to maintain relationships with a large number of external partners it creates a high resource programme which puts pressure on business cases. The maze of Standards, assessments and collaboration with learning providers is much more complex compared to conventional patterns of recruitment. What’s more, the recent collapse of the Tech Partnerships has exacerbated the sense of risk. Given the proportion of engineering jobs that are in SMEs and that these firms represent significant economic activity in areas that the Government’s Levelling Up Strategy aims to support, failure to make Apprenticeships attractive to these employers is potentially damaging not only to the future of apprenticeships, but to the whole economy.

Similarly, for prospective apprentices, teachers, careers advisers, and parents the apprenticeship landscape looks unfamiliar and complex. When compared to the path-of-least-resistance process of university application through UCAS, discovering degree apprenticeship opportunities, applying to them and surviving what is often a number of recruitment rounds looks like an obstacle course.

While some students regard degree apprenticeships as more attractive than the more traditional student experience with its attendant debts, others see it as missing out on traditional student life in order to tie themselves to one employer and one career pathway.

Based on the data available to date of apprentices’ socioeconomic backgrounds, degree apprenticeships have failed to widen access to higher education significantly. Employers do not face the same drivers for fair access that more traditional university pathways are subject to. For apprenticeships to widen the talent pipeline, they need to create opportunities for wider access rather than merely divert the current stream.

The focus on industry driven (or industry group driven) curriculum means that some universities that are keen to offer apprenticeships are reluctant to do so due to the level of development needed, lack of reuse of existing material and the (perhaps perceived) loss of control of the curriculum. In the engineering field, the need for local business and university collaboration means that providers feel they are only able to develop programmes in areas where they already have strength and relationships. This leads to many institutions only offering one of two programmes.

for young people in accessing them?

1. Standards tend to be ‘employer-dominated’, not ‘employer-led’.

Our membership has reported repeatedly that degree apprenticeship Standards can be too narrow. This arises because the development of a Standard has been led by a small number of employers who base it on their experience of needs. Once a Standard has been established, competing Standards cannot be recognised. However, if the standard does not reflect the wider needs of employers and the apprentices’ need for skills, knowledge and behaviours, then the standard blocks the space for a more widely appropriate standard. As a result, some Standards are likely to be underutilised even while the need for an apprenticeship in that area remains. The problem may be especially acute for SMEs, which account for at least 99% of the businesses in every main industry sector in the UK and 60% of all private sector employment in the UK.

Their needs as employers – which differ significantly from those of large employers’ – may have been overlooked, as large employers have been dominant in Trailblazer groups.

It is interesting to note that the digital space – with fewer and much broader standards – has positively flourished compared to the engineering and technology sector. In engineering it seems no coincidence that by far the most popular standards are also the broadest, Manufacturing Engineer and Product Design and Development,

2. Lack of discoverability

Compared to traditional degrees, degree apprenticeship opportunities remain harder for students to find and the application process can be challenging.

3. Learning experience and outcomes

Apprenticeships that fail to provide positive learning experience and positive outcomes are doomed to fail. Non-completion rates from degree apprenticeships are significantly higher than for traditional degree programmes and, in additional to the risk of failure or disaffection of the part of the apprentice, there is the added risk of commercial precarity or strategic changes of direction by employers.

Apprentices need to acquire useful and relevant skills and knowledge that prepare them well for a career in engineering, rather than simply a job. This is a particular risk in the field of upskilling adults; knowledge gained is essential.

4. Inclusion

Degree apprenticeships have the potential to attract different kinds of learners into higher education and training, particularly those from less advantaged backgrounds for whom the financial implications of study may be a deterrent factor. Currently employer groups are involved in some FE/HE outreach consortia, but few employers themselves. This contrasts with the efforts of the Careers and Enterprise Company, which is attempting to encourage greater direct engagement between employers and schools. The approach of both outreach initiatives and the Careers and Enterprise Company is, however, not entirely consistent with the DfE’s guidance to schools on careers education that it should be “independent and impartial”, which is hard to reconcile with delivery by employers or consortia of educational institutions.

5. Sense of belonging

Research shows that learning is enhanced by a sense of collective belonging and that this reduces the tendency to drop out. This is particularly important for learners from academically non-traditional backgrounds and mature learners. Employers (and HEIs working with them) need to identify ways of enhancing engagement as part of a learning community. Research commonly shows that teaching non-traditional students in mixed cohorts with their peers, where both groups will learn from each other, can be really effective teaching and learning practice. Apprentices would also benefit from evidence of best practice support for learning in degree environments. Opportunities to engage in co-curricular and social experiences, many of which also contribute to broader employability skills, may also be an existing good practice for providers of degree apprenticeships to consider adopting. This might be possible as a solution provided by the employer in the case of a large cohort of apprentices, but for smaller employers and large employers employing small numbers of apprentices, it will be necessary to consider how to integrate apprentices into a community within their working environment and/or within their study environment (with the wider student body and/or with degree apprentices from other employers).

6. Apprentices’ welfare and representation

Within the traditional student community, students usually have access to welfare and support services ranging from pastoral care to child-care facilities. Providing such support to a wider range of more disparate students will require staff training and appropriate resourcing. Moreover, students’ interests are represented through their student unions and employee interests through trade unions (when recognised). However, the representative body for apprentices in the workplace can be unclear. Employers need to consider representation of apprentices as a cohort in their organisation. It may be that parallel systems would operate effectively, but particular consideration should be given to the appropriate processes for assessment appeals.

7. Learning support and enhancement

The aim must be to establish degree apprentices as future engineering graduates with enhanced workplace experience. To this end, it is important that their academic experience is not a compromised version of that provided for traditional degree students. Degree apprentices on existing programmes have expressed the importance of teaching hours in a range of formats (workshops, webinars etc). Individual apprentices may start out with significant differences in experience and prior attainment.

8. Mode of study

A modular approach to return to study without committing at day one to a full degree could help attract more mid-career apprentices and their employers to the scheme, and better support equality and diversity. However, a fully ‘hop-on, hop-off’ approach is effectively precluded by the current framework for funding and apprentice Standards. In addition, the digital account system makes this difficult to manage. This must be addressed by the Government as it develops its plans for lifelong learning.

9. Expectations

Misunderstanding about the division of responsibilities between employers and HEIs can lead to poor outcomes for both parties and particularly for the apprentices. As the number and range of employers offering degree apprenticeships grows, the lack of standardised expectations presents a risk to the capacity of HEIs to deliver.

10. Developing partnerships

The relationship between higher education institutions (as training providers) and employers is critical to developing and running successful degree apprenticeships. the history of partnership between business and education is littered with good intentions and clashing cultures.

11. The needs of SMEs have been sidelined

Trailblazer groups tended to comprise primarily of large employers usually offering programmes to a large number of apprentices. They have well-resourced HR departments and organisational structures that allow support systems for apprentices to be put in place. As they may have a cohort of apprentices each year, rather than single individuals, those apprentices also gain from a sense of belonging. However, this means that employer-led degree apprenticeships have not been led by organisations that are representative of employers of the majority of the UK workforce (and the majority of workers in the engineering sector in particular). SMEs face very different challenges to large employers and it has not been in the competitive interest of large Trailblazer firms to ensure the system is well-designed for smaller employers.

12. A menagerie of outputs

As currently conceived, an engineering degree apprenticeship has four discrete outputs:

• A degree, awarded by the HEI, which is usually accredited by one of the professional engineering institutions;

• An end-point assessment (EPA), assessed by a registered EPA organisation;

• Continuing employment, decided by the employer;

• Evidence towards professional registration (with registration subject to individual candidates being assessed by a professional engineering institution professional review processes, which may in some instances be incorporated into the EPA and in other cases be completed at a later stage after completion of the apprenticeship).

These are all independent of each other, although interdependent, and it would be possible for an apprentice to pass or achieve some but not all of these outputs. This diversity of outputs, each subject to their own assessment criteria and process is confusing even to experts and baffling to most employers and apprentices, let alone parents, teachers, careers advisors across all ages and HR departments. Promoting a broad appreciation of the benefits of a degree apprenticeship operating under such a framework is, at best, a challenge and, at worst, unworkable.

13. Engineering degree apprenticeships are not aligned to professional recognition

Apprenticeships should have a fair and rigorous system of assessment and recognition that is aligned to professional progression and should result in competent and qualified engineers who are able to demonstrate their professionalism according to the framework of recognised sector Standards.

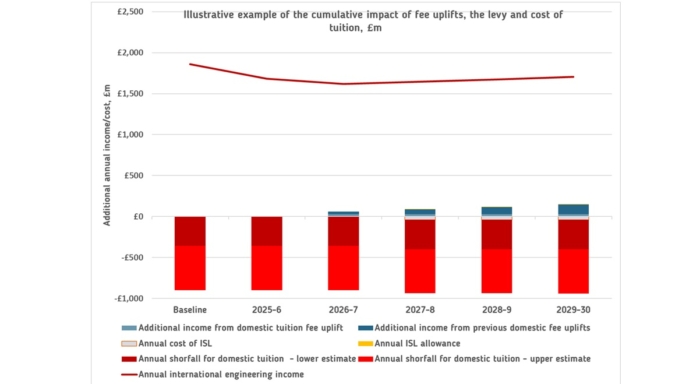

14. Financial sustainability

From the perspective of higher education institutions, the levy-funded fee for an engineering degree apprenticeship is capped at £27,000 (which also has to cover the cost of the end point assessment), whereas the maximum fee level for a traditional engineering degree is currently £37,000 (assuming a four-year course), sometimes with a supplementary teaching grant (particularly for Chemical and Materials Engineering). Commonly, the cost of teaching engineering degrees exceeds the direct funding. This discrepancy means degree apprenticeships have to be delivered at a considerable cost saving compared to traditional degrees.

It may be argued that savings should be possible because the workplace learning could potentially mean lower teaching intensity and assignments. However, degree apprenticeships also carry a high burden of communication and liaison and may require different teaching and learning approaches for students with different academic needs. Employers are also concerned that the levy-funded fee is not sufficient to train a degree apprentice. The EEF estimates an engineering apprenticeship (not necessarily an engineering degree apprenticeship) costs £80-90,000 to offer and deliver.

Moreover, unlike traditional degrees, which are funded upfront, degree apprenticeships carry a greater financial risk and uncertainty for HEIs, not least because 20% of funding can be held back if an apprentice does not complete their end point assessment. Given all the challenges described above, it must be assumed a significant proportion will indeed drop out or fail. If engineering degree apprenticeships are to see a rapid period of expansion, there will be higher overheads and up-front costs as systems and infrastructure are put in place. There will need to be innovation and experimentation as best practice is developed. During this period, the revenue from the Apprenticeship Levy is likely to continue to outstrip the spending.

15. Parity of esteem

Over many decades vocational and technical pathways have failed to gain parity of esteem with traditional academic routes. The branding of apprenticeships is problematic as the name carries connotations of low status with young people and their influencers. This amounts to a sense that an apprenticeship is junior, whereas a degree is aspirational. Seeing entry to traditional university programmes as a success and entry to apprenticeships as a failure in school success measures (and the consequent use of those metrics in league tables) is a huge problem anecdotally.

up and completing engineering and technology apprenticeships?

Government

• Government needs to urgently address the complexity of messaging around degree apprenticeships and develop a centralised approach to raising awareness among prospective apprentices, providing information about options, brokerage and establishing shared application platforms.

• The term ‘degree apprenticeships’ has negative associations for some potential apprentices, being linked in their perceptions to lower level apprenticeships. We recommend that the Department for Education (DfE) explores opportunities to introduce more aspirational terminology and IfATE commissions urgent research into attitudes to different terminology.

• Government should adopt metrics that incentivise school management to support pathways into degree apprenticeships as equivalent to other forms of higher education.

• The OfS and the Government should explore ways to ensure evidence-based, early-intervention outreach is well funded. The EPC believes that the appropriate promotion of apprenticeships is a reasonable component of the cost of providing them. Employers should be allowed to offset the cost of independent and impartial outreach work against a proportion of their Apprenticeship Levy in the same way as they can currently use 10% of the levy to employ subcontractors. In order to avoid this becoming a means to offset the employers’ recruitment costs, only independent and impartial outreach should qualify.

• A body of research into the effectiveness of – and best practice for – degree apprenticeships needs to be developed. This should be undertaken by IfATE, by the OfS and/or by Advance HE, and it is the DfE’s role to ensure this responsibility does not fall between the cracks in this fast-evolving area of practice.

• To facilitate innovation and experimentation as best practice is developed, and to offset higher overheads as systems and infrastructure are put in place for degree apprenticeships in engineering, it is important they are adequately resourced. For a five-year period, when the revenue from the Apprenticeship Levy is likely to continue to outstrip the spending, the Government should either immediately raise the engineering degree apprenticeship fees or provide catalyst funding to support the development of programmes.

• Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) employ the majority of workers in the engineering sector and face very different challenges to large employers. IfATE and the Government should conduct a review into the particular challenges for SMEs in the delivery – and ensure that SME voices are heard in the development – of degree apprenticeships.

• The Government and IfATE must urgently consider how to ensure non-completion (for reasons other than failure) is not a dead-end for the apprentice. Credit transfer and modularity would be helpful, alongside a funding resource that apprentices can access in case of premature cancellation of an apprenticeship programme.

Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education

• A modular approach to study would help attract more mid-career apprentices yet a fully ‘hop-on-hop-off’ approach is effectively precluded by the current framework for funding and by apprenticeship Standards. IfATE should review its policies to explore ways to introduce greater flexibility.

• Degree apprenticeship Standards can be too narrow. IfATE must ensure that development of Standards is a more open and ongoing evolution, allowing greater input from learning providers before and after the establishment of the Standards. Ensuring that SME voices are heard in the development of degree apprenticeships is a real opportunity to ensure the sector will be inclined to engage in the delivery of apprenticeships.

• IfATE must ensure that the development of Standards is a more open and ongoing evolution, allowing greater input from learning providers before and after the establishment of the Standards. This may lead to potential conflict with those employers that have an objective to develop deeper specialisms, but it should be recognised that an apprenticeship that fails to serve the long-term interests of the apprentice will not be in the interests of the employer either.

• IfATE must conduct a continuous process of reviewing under-utilised Standards or those used by only a small number of employers. Where necessary, steps should be taken to ensure that, unless they serve a niche role, Standards have broad applicability to multiple employers. Apprenticeships should promote flexible employability skills and skills across different and ever-changing areas of engineering. With this in mind, IfATE should ensure Standards always align with pathways towards professional recognition.

• If research demonstrates that the Standards fail to protect – and enhance – parity of esteem, then the Government must be prepared to raise the funding for engineering degree apprenticeships permanently to avoid damage to their reputation. The DfE must ensure the future of post-18 education funding considers support for degree apprenticeships.

Employers

• The fact that degree apprenticeships are employer-led must not create an incentive to train apprentices simply for a specific job, but rather for a career.

Regulatory and professional bodies

• Regulatory and professional bodies must give consideration to where in the sector additional professional registration assessors will come from and opportunities to streamline the process for degree apprentices who achieve their degrees and pass their End Point Assessments (EPAs).

Office for Students

• Apprentices should participate in the national Student Survey (NSS) and OfS must consider how to recognise apprenticeships in the TEF. Due consideration needs to be given to the potential impact on benchmarks for HEIs that provide a large number of apprenticeships.

• Degree apprenticeships should be explicitly considered as part of the OfS’s strategy for wider access, participation and retention. This will entail closer alignment of collaborative outreach strategies with the Government’s Careers Strategy in terms of working with employers to deliver effective outreach and working with schools to deliver outreach that encourages learners to find the pathways that suits them best.

• The OfS should support the Gatsby Benchmarks in terms of working with employers to deliver effective outreach and working with schools to deliver outreach that encourages learners to find the pathways that suits them best.