The EPC has responded to the Education Committee Inquiry: Higher Education and Funding: Threat of Insolvency and International Students.

The inquiry looked into into the financial viability of universities as they face the challenges of rising costs and falling numbers of international students after years of tuition fee freezes, following an Office for Students report outlining the declining financial health of the sector, and warning that it may not be able to rely on the recruitment of international students for financial stability in the years ahead.

Summary of our response

Engineering is a strategically critical subject and a key driver of economic growth, with engineering accounting for nearly a third of the entire value of the economy. It drives key government mission and opportunity, including the new industrial strategy, and is a powerhouse of regional development as it is spread remarkably evenly throughout the country.

Engineering is at the financial sharp end of the inquiry’s focus. A structural £8k annual underfunding per domestic undergraduate student means that expanding student numbers does not help dilute fixed costs. Instead, each additional home engineering student deepening the deficit, as losses increase as enrolment rises. Providers are mitigating this phenomenon by actively flatlining recruitment in a buoyant applicant market.

Within the current funding model, international student fees operate as the only viable cross-subsidy. International student recruitment is already critical to balancing budgets, without which Engineering programmes are essentially insolvent. Any disruption to international enrolments risks destabilising engineering faculty finances and could precipitate insolvency at departmental or provider level. Adding the proposed Government six per cent international tuition fee levy would be unworkable and OfS’s forecast to improve sector finances with overseas recruitment is overambitious.

Government policy should recognise international engineering students as strategic assets. International engineering students are a critical part of the UK’s future skilled workforce. Restricting this talent pipeline via visa constraints undermines national industrial and innovation strategies.

There is now an urgent need for realignment of funding to actual course delivery costs and to enhance and sustain international student pipelines (including by resisting visa cost increases).

Engineering may be the canary in the mine when it comes to departmental or institutional insolvency with increasing engineering programme demand pressure being actively mitigated supply-side. It is uniquely vulnerable to the deteriorating financial performance of providers reportedly driven by “broadly flat student recruitment and increasing costs”[1]. However, EPC admissions research finds that the flatlining of recruitment in engineering is provider – not applicant – driven[2].

Applications to undergraduate engineering courses increased by nine percent between 2023 and 2024[3] and by 14 percent (to engineering and technology) by the January 2025 equal consideration deadline[4]. The upsurge in interest in engineering can be seen as part of a “swing to STEM” (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). As higher education has shifted to a reliance on student debt for funding, many people suspect applicants have felt greater pressure to search for clear, transactional returns which, it may seem, are offered most explicitly by STEM – and, most particularly, by engineering, which is not just STEM, but vocational too.

However, last year’s rise in applications did not lead to a rise in the number of UK engineering students. Absolute student numbers have more or less stagnated since 2019. Instead, we find that providers are rejecting far more engineering applications than five years ago (+20 per cent between 2019 and 2023 – that’s 55 thousand engineering rejections in 2023 alone), with increasing demand pressure being actively mitigated supply-side.

The UCAS data also show higher tariff institutions are the main beneficiaries of application increases at the expense of lower tariff institutions which, traditionally have a wider access intake.

What this means is that the increased demand for engineering places will not lead to a rise in engineering student numbers, let alone in skilled engineers, but rather a narrowing of the access to engineering such that it becomes ever harder to get in without the highest grades. High prior attainment correlates closely with socioeconomic advantage and so, rather than engineering playing to its strength of driving social mobility, it will run the risk of becoming ever more privileged.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global change confirms that the impact of both the changes enacted by the previous government and these latest reforms will not be uniformly felt, with the post-1992 institutions more likely to be affected. “The universities with the least [financial] headroom, or deficits, are often vital to local opportunity in less wealthy places outside London and the South East”.[5] Policies that help more pupils apply to lower tariff institutions could be considered.

Clearly, providers are already and continually reassessing recruitment forecasts and risk portfolios and there are differences by provider type. In engineering overall, this means a reduction in domestic undergraduate engineering students due to the deepening of deficit caused by structural underfunding.

The key financial sustainability assumption – that expanding student numbers helps dilute fixed costs – is not viable in engineering. The OfS expected recovery trajectory is based on 26 per cent growth in UK student entrants. But with each additional home student actually deepening the deficit in engineering, such growth in home engineering students is simply unviable. What’s more, the increase in applications to undergraduate engineering is driven by 18-year-olds (+18 per cent since 2019) yet the 18-year-old UK population is about to drop off and there are no signs of an increase in all-age participation (the number of engineering applications from those aged 20+ has fallen by nine per cent since 2019). Increasing all age participation is a policy opportunity, and we welcome tying LLE funding for Level six modules to “priority subject” degrees and the industrial strategy. However most existing engineering degree programmes weren’t designed to be broken into standalone modules. Simply dismantling them into bite-sized units is a financial burden that universities cannot bear in the current financial climate and needs further consideration of how credits can be transferred between providers, particularly on accredited pathways. Demand side, many adults will be reluctant to take on more debt—even if it’s in the form of flexible student loans. This debt concern could deter the very learners the LLE is meant to support.

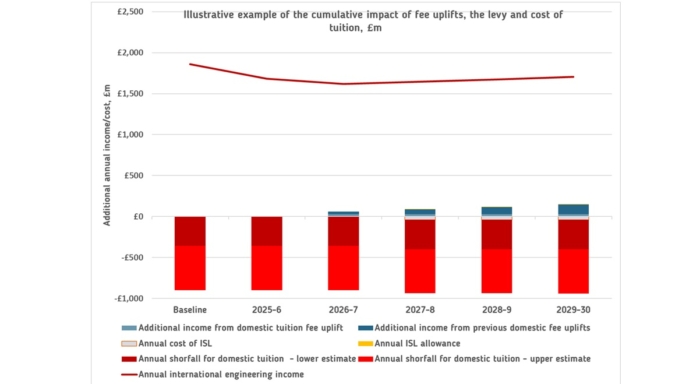

EPC modelling shows that undergraduate engineering courses cost ~£18–19 k/year to deliver per undergraduate[6], yet home student funding is only ~£9.5 k, rising to ~£11 k with high-cost top‑ups. This creates a £8 k+ shortfall per domestic undergraduate student, which isn’t merely a marginal loss – it actively increases losses as enrolment rises. The EPC estimate that the annual underfunding of domestic engineering provision equates to more than £897.5m.

Quality engineering education is expensive[7] and structurally unsustainable without reform as each additional home engineering student deepens the deficit. Engineering courses typically require the use of specialist facilities, equipment and materials (within regulated and internationally recognised Engineering Council Standards) with providers left footing 44 per cent of engineering course running costs from other sources. However, with declining cross-subsidy from arts and humanities, macro-level financial stress is increasingly felt across engineering faculties, raising the spectre of departmental or institutional insolvency.

Government should re-align domestic discipline-specific funding to actual course delivery costs: 1) in the short term through uplift to existing SPG and very high-cost funding mechanisms; 2) through more radical solutions such as loan right offs for accredited degrees; and 3) a radical reassessment of HE funding through alignment of student ambitions and choices and the labour market.

Should it look likely that a provider of accredited engineering degrees might close due to financial issues, disadvantaging students unable to complete an accredited programme, policy makers should engage with the Engineering Council as early as possible.

Within the current funding model, international student fees operate as the only viable cross-subsidy, effectively propping up underfunded home student cohorts. Engineering programmes are essentially insolvent without a comparative increase in international fee income additional to that modelled by the OfS.

However, OfS trajectory modelling to improve sector finances – including a 19.5 per cent uplift in international student recruitment[8] – is overambitious. The required infrastructure beyond the sector norm to host an additional 11.5 thousand international enrolments – including specialised labs, equipment, materials and above average staff intensity[9] to deliver hands-on engineering education – are not scalable in the way that non-lab-based subjects are.

This outlook also puts extreme pressure on engineering, the third most popular subject in UK universities internationally, and currently accounting for eight percent of all international student enrolment. One in four engineering undergraduates are already international, suggesting the international recruitment ceiling in engineering is closer than in other subjects. If engineering departments had the capacity to recruit more international students, they would probably already be doing it. Providers have already factored in increases to international fees to account for rising costs over the next five years. Adding the proposed Government six per cent international tuition fee levy on top of that would be unworkable.

At undergraduate level, the average fee charged to international engineering students is already £23,194 for the 2025/26 session, up from £19,536 in 2022/23. The average for the Russell group now stands at £33,470 (up from £28,762 in 2022/23), whereas in non-Russell Group Pre-92 institutions it is £24,114 (up from £19,509 in 2022/23) and in Post-92 institutions, £17,205 (up from £14,729).

Most universities, even if they could attract more international engineering students, would no longer use the extra income to expand engineering for home students, but rather to shore up the existing deficits of maintaining current levels. Government should urgently embed international recruitment into a sustainable funding strategy, rather than allowing it to remain the only viable backfill for domestic underfunding.

With deficits deepening per domestic student, international student recruitment is now critical to balancing budgets. With OfS (2025) predicting a deteriorating outlook for 2024-25 due to a 21 per cent reduction in new international student entrants compared with last year’s forecasts, the “cuts in courses, staff, and maintenance” will be disproportionately and acutely felt in engineering. In 2023-24, 23 per cent of engineering undergraduate enrolments were international, compared to 14 per cent for all other subjects. This increased to over 70 percent at postgraduate level compared to 50 percent for all other subjects.[10] We estimate that overall student fee income in engineering in England and Wales (at UG and PGT level) is just shy of £2bn per year, approximately 10 per cent of the fee income to the sector as a whole. While in 2022 this was roughly equally split between home fees and overseas fee income (which now includes European students) by 2025 the overseas student income increased to 60 per cent of the total.

Any disruption to international enrolments risks destabilising engineering faculty finances and could precipitate insolvency at departmental level. Our members are already reporting departmental-level staff cuts and research closures, with expected severe long-term quality, as well as capacity, impacts. The link between HE funding, the government’s international education strategy and quality requires policy attention. The UK’s reputation for world class engineering education is under threat if departments are under-funded, and international students with an increasing number of alternative options start to perceive those as delivering a better experience and better outcomes. Looking at the range of countries now represented in Washington Accord, and the Times Higher International suggests that without capacity to keep pace, the UK’s ability to attract engineering students could rapidly erode.

The loss of international income at scale may trigger immediate solvency issues at institutional level for heavily engineering‑focused institutions. The danger is systemic: universities with higher engineering concentration (often outside London) are disproportionately exposed. An EPC report in 2020 showed that circa 40 higher education providers’ engineering and technology provision was dependent on international students (> one third of the engineering student population), with a handful of providers whose international student enrolment was dependent on engineering (> one third of international student enrolment was in engineering).[11] This has undoubtedly proliferated since then and the EPC would be pleased to update the report for the committee’s consideration.

While international students are an asset in every way, they are not generally adding to the engineering skills pipeline as more than 95 per cent do not stay in the UK for more than 5 years after graduation. However, the recent tightening of student visa policy, including the ban on bringing dependants (effective from January 2024), has created uncertainty and discouraged international applicants, particularly from key markets such as Nigeria. Increases in the Immigration Health Surcharge and visa application fees have compounded the issue, making the UK a less attractive study destination relative to global competitors like Canada, Australia, and Germany.

Policy objectives on immigration and university funding should be considered alongside each other and Government policy should recognise international engineering students as strategic assets, both financially and in workforce development, rather than as a target for net migration reduction. Given the dependency of domestic engineering education on international students, free flow of international engineering talent should be a priority for this Government unless and until we can address the shortages in the domestic talent pipeline. According to the British Chambers of Commerce, it’s pretty much the largest skills gap in the UK economy.[12]

International engineering students not only support university finances — they also form a critical part of the UK’s future skilled workforce. Many progress into high-value roles in UK industry post-graduation (but typically for less than five years) especially in shortage areas such as civil, electrical, and mechanical engineering. Restricting this talent pipeline via visa constraints undermines national industrial and innovation strategies, particularly as UK engineering faces an ageing workforce and chronic skills gaps. A CBI report highlights that the one of the main current threats to the UK’s labour market competitiveness is access to skills (72 per cent) and that closing future skills gaps could provide a £150 billion uplift in GVA by 2030. Government needs to stabilise, protect and enhance international student pipelines, by providing visa stability, reduce visa/fee burdens to maintain UK attractiveness and restore confidence in the system. It should also halt further visa fee increases (e.g., IHS, visa costs) and consider post-study work incentives to encourage longer-term economic contribution.

Engineering is a key driver of the growth that the government is so keen to stimulate, adding £645b to the UK economy[13] – that’s nearly a third of the entire value of the economy. And engineering is a powerhouse of regional development as it is spread remarkably evenly throughout the country.[14] An engineering degree confers a higher and more equal graduate premium than almost any other discipline.[15]It also drives that other key government mission and opportunity, including the new industrial strategy.

[1] https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/0zmhglew/ofs-2025_26.pdf

[2] https://epc.ac.uk/article/epc-outlines-a-provider-led-ceiling-on-admissions-and-changing-supply-and-demand-behaviours/

[3] https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-end-cycle-data-resources-2024

[4] https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-releases/applicant-releases-2025-cycle/2025-cycle-applicant-figures-29-january-deadline

[5] Data Decoded: UK Higher Education, Immigration and Financial Sustainability

[6] https://epc.ac.uk/article/policy-post-spring-2025/

[7] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909417/Measuring_the_cost_of_provision_using_transparent_approach_to_costing_data.pdf

[8] https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/0zmhglew/ofs-2025_26.pdf

[9] HESA HEIDI+

[10] HESA HEIDI HE All Providers Student FPE 2023/24 as at 23/7/25 Full person equivalent % broken down by Domicile (basic) CAH level 2. The data is filtered on Academic Year and Level of study (detailed 4 way).

[11] https://epc.ac.uk/article/how-will-the-probable-collapse-in-international-student-numbers-as-a-result-of-coronavirus-affect-uk-engineering-departments-weve-crunched-the-numbers/

[12] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/The_Open_University_Business_Barometer_2024.pdf

[13] https://raeng.org.uk/news/a-hotbed-of-innovation-new-research-reveals-engineering-adds-up-to-an-estimated-645bn-to-the-uk-s-economy-annually

[14] https://www.engc.org.uk/media/4587/mapping-the-uks-engineering-workforce.pdf

[15] https://epc.ac.uk/publication/engineering-opportunity-maximising-the-opportunities-for-social-mobility-from-studying-engineering/