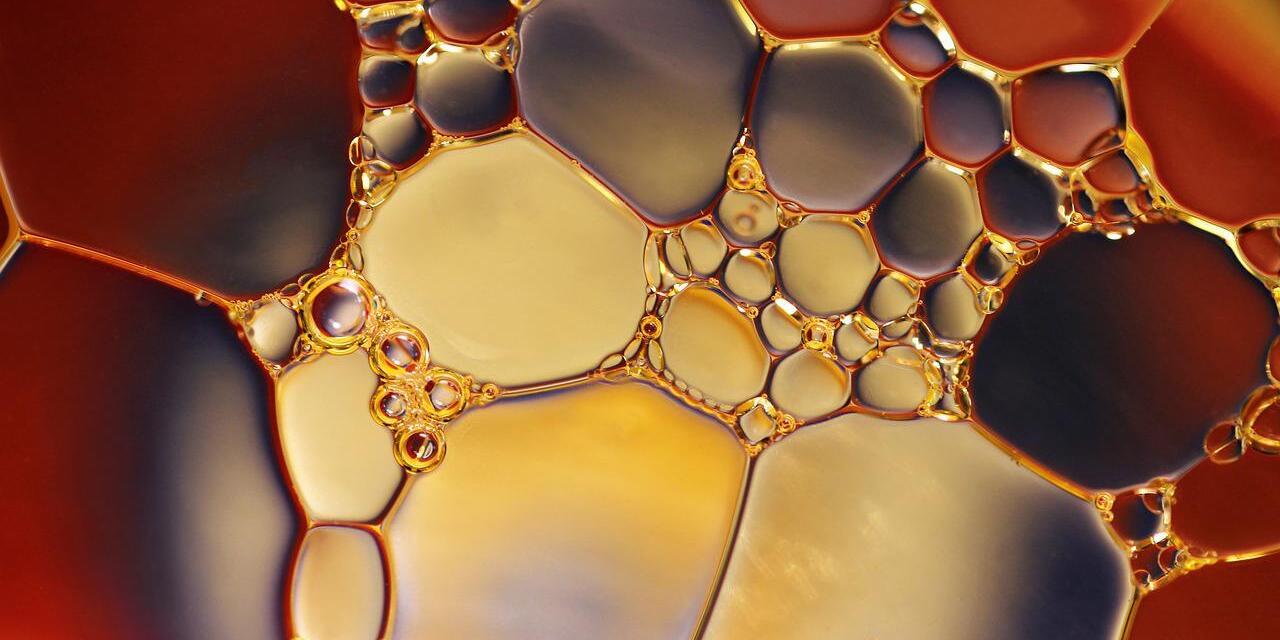

The two culture of arts and sciences are like oil and water, but, asks Prof Mehmet Karamanoglu, could they be mixed? Indeed, perhaps it’s essential that we get them to learn from each other?

The higher education sector has been battling with the issue of introducing ‘creativity’ into engineering education for decades, as if this never exists in engineering programmes.

Many institutions in the UK have tried to address this by creating collaborative programmes between departments of Engineering and Art & Design. The academic programme often sits in an Engineering department with modules from the Art & Design department, but less so the reverse.

Over the past 30 years, I have seen such projects come and go and the end result has been the same – not a positive experience for students or staff involved. It goes without saying that there are also issues in the use of the terminology – we often talk about ‘Arts and Sciences‘, but what we really mean is ‘Design and Engineering‘.

In an attempt to explain why such collaborations have not been successful, we often put this down to the fact that the two areas have their own cultures. This gives rise to the term you now see used by the media and politicians, the ‘Two Cultures‘: although the term has been used in academic debate for decades since C P Snow’s lecture of that name in 1959.

To look at this more closely, first we need to understand the obstacles that get in the way. Let’s call these two cultures, Camp A and Camp S.

Some key characteristics:

- Camp A has a monopoly on the word ‘creative’ and no other camp can use it.

- Camp S does not associate itself with the word ‘creative’ even though it practices it daily to solve problems.

- Camp A hates structures and rules, an inherent part of its often rebellious makeup.

- Camp S cannot operate without structures and rules – operates systematically and hates change.

- Camp A is territorial even within itself. Not really happy to share resources. Each of its constituents operates in an autonomous mode.

- Camp S is territorial externally but unified within itself.

- Camp A are divergent thinkers, hate constraints, often not interested in the end result but the journey it takes and the experience of that journey. The destination is often irrelevant.

- Camp S applies constraints too soon and arrives at a destination but may miss vital opportunities along the way. It operates too rigidly.

- Camp A practices team teaching, often with contradictory views among its members.

- Camp S operates in solo mode – one class, one master.

- Camp A showcases their work and teaches by teams of staff. Each team owns their programme and has their own work space.

- Camp S keeps their work preserved for themselves, does not show off.

Barriers to making the two camps work together:

- Financial barriers – budgets that are devolved to individual camps is a key obstacle and will lead to effort being spent on counting pennies than producing useful work.

- Having own physical facilities – ends up in duplication of resources, neither as good as they ought to be.

- Lack of trust, value and respect in each other’s way of working.

- Each camp retaining their work environments and students visiting each camp for their studies.

- If this is an academic programme, as the approaches are so different, this will set some serious confusion for students, they will end up as academic schizophrenics.

My personal experience to crack this issue:

- Do not force the two camps to come together artificially. It is akin to making an academic emulsion but with far worse side effects. So many try to create joint ventures or programmes, but blending the two cultures from two separate entities does not work as they always preserve their inherent make-up. Short term success is possible, but it is not sustainable. It relies heavily on individual personalities which often clash and so the success does not last.

- The only successful way that has stood the test of time is to grow a single but a mixed-culture camp from scratch. In the camp you will need staff with Camp A and Camp S characteristics, but the critical point is that they belong to the same camp.

- There are no financial barriers – it is a single camp with a single budget. In fact, take the staff cost out of the camp’s budget to the next layer up and what is left is not worth arguing about.

- There are no mine-and-yours physical resource issues. It is all ours.

- Most critically, Camp A and Camp S type staff will depend on each other to survive, learn to get on together and accept that there are different ways to do things for both. In other words, accept, value and respect each other.

- The mixed-camp needs to be given time to evolve and this will take a while. The more urgent the survival becomes, the sooner the integration will happen. Once established, the new camp develops its own culture.

Having been through such an experience myself in 1996 at Middlesex University, it took four years to realise that operating as two separate camps would not work, so I started from scratch. Now, nearly two decades down the road from setting up the Design Engineering Department, there is no looking back, but I’ll probably always remain a recovering engineer.

To return to my opening point, it is not that we wanted to introduce ‘creativity’ into our engineering programmes, but rather it was actually about changing our practice and our way of doing things in order to acknowledge the evolving nature of the discipline, which has became practice-based. It was this that led to the creation of what I call the three pillars of practice-based learning in this new camp:

- A curriculum model that recognises the appropriate teaching, learning and assessment approaches needed;

- A physical Environmentthat supports the pedagogy adopted;

- Staff resourcesthat can embrace the pedagogy adopted and operate within the environment created.

Prof Mehmet Karamanoglu is Professor of Design Engineering and Head of the Department of Design Engineering and Mathematics at Middlesex University, London.